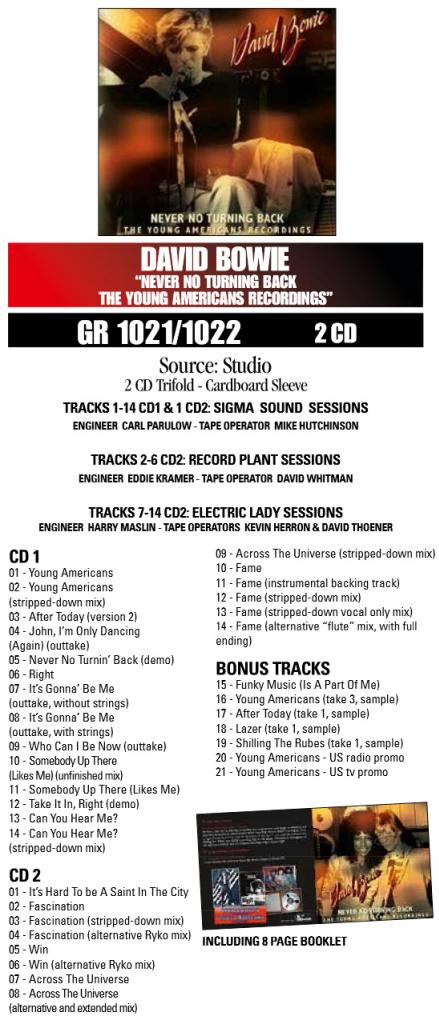

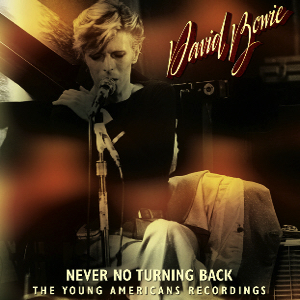

David Bowie Never No Turning Back (The Young Americans Recordings).

Sound Quality Rating

01. Young Americans – Stripped Down Mix (1).

02. After Today – Version 2 – 2003 Remaster.

03. John, I’m Only Dancing (Again) – Outtake – 2007 Remaster.

04. Right – Vocal Rehearsal – Excerpt from ‘Cracked Actor’ Documentary.

05. Never No Turnin’ Back (Right) – Demo.

06. Right – Alternate Ryko Mix.

07. It’s Gonna Be Me – Outtake – 1991 Remaster.

08. It’s Gonna Be Me – Strings Mix – 2007 Remaster.

09. Who Can I Be Now – Outtake – 2007 Remaster.

10. Somebody Up There Likes Me – Unfinished Mix.

11. Take It in Right (Can You Hear Me) – Demo.

12. Can You Hear Me – Stripped Down Mix.

13. It’s Hard to Be a Saint in the City – Outtake – 1998 Remaster.

14. Fascination – Stripped Down Mix.

15. Fascination – Alternate Ryko Mix.

16. Win – Alternate Ryko Mix.

17. Across the Universe – Alternate Extended Mix.

18. Across the Universe – Stripped Down Mix.

19. Fame – Instrumental Mix.

20. Fame – Stripped Down Mix.

21. Fame – Isolated Vocal Mix.

22. Fame – Alternate Flute Mix.

23. Funky Music (Is a Part of Me).

24. I’m Divine.

25. I Am a Laser.

26. Young Americans – Take 3 – Excerpt.

27. After Today – Take 1 – Excerpt.

28. Lazer – Take 1 – Excerpt.

29. Shilling the Rubes – Take 1 – Extended Excerpt.

Label : The Godfather Records – GR 1021-1022

Audio Source : Studio recordings

Lineage : Unknown

Total running time : 2:04:16

Sound Quality : Excellent quality! Equals record or radio

Artwork : Yes

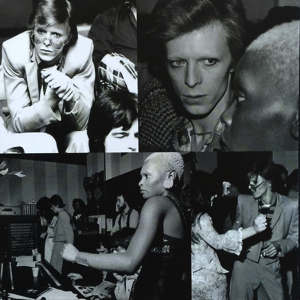

At the end of the first leg of the Diamond Dogs tour and armed with some new material, David Bowie booked into Philadelphia’s Sigma Sound Studios in August 1974 to lay down some tracks for a new album. For this album, David let go of the influences he had drawn from in the past, replacing them with sounds from local discoteques and dance halls, which, at the time, were blaring with lush strings, sliding hi-hat whispers, and swanky R&B rhythms of Philadelphia Soul. David is quoted describing the album as “…the squashed remains of ethnic music as it survives in the age of Muzak rock, written and sung by a white limey”. Because of the strong influence of black music during the album’s recording sessions, David used the term “plastic soul” (originally coined by an unknown black musician in the 1960s) to describe his new sound. Although David was an English musician bringing up touchy American issues, the album was still very successful in the United States; reaching the top ten in the US, with the single ‘Fame’ hitting the number-one spot the same year the album was released.

In order to create a more authentically soulful sound, David brought in musicians from the funk and soul community, including Andy Newmark, drummer of Sly and the Family Stone, and an early-career Luther Vandross. Luther brought along two of his backing singers, Anthony Hinton and Diane Sumler, who together with Ava Cherry joined David during the sessions.

“I’m putting a very good new band together. There’ll be three people from the ‘Diamond Dogs’ album, Mike Garson on piano again, Herbie Flowers on bass, yeah I managed to persuade Herbie to tour with me, and y’know he’s got to be the best bassist in the country, and there’s Tony Newman who used to drum in the old Jeff Beck Group.

“I’ve also been looking for guitars, and I’ve found a really incredible black guy called Carlos, just Carlos! and there’s another black guy I want to get to play guitar in the band. I want a really funky sound.”

“Ever since I got to New York I’ve been going down to the Apollo in Harlem. Most New Yorkers seem scared to go there if they’re white, but the music’s incredible. I saw the Temptations and the Spinners together on the same bill there, and next week it’s Marvin Gaye, incredible! I mean I love that kind of thing!

“Have you heard Ann Peebles? Yeah, well Lennon’s right, ain’t he, best record in years. I mean that’s what I’d like to do producing Lulu, take to Memphis and get a really good band like Willie Mitchell’s and do a whole album with her, which I will do.

“Lulu’s got this terrific voice, and it’s been misdirected all this time, all these years. People laugh now, but they won’t in two years time, you see! I produced a single with her — ‘Can You Hear Me’ — and that’s more the way she’s going. She’s got a real soul voice, she can get the feel of Aretha, but it’s been so misdirected.

“English singers do all this ‘Oh yeah’, ‘Alright now’ on soul songs, and it’s wrong, but when she doesn’t do that she just has the feel naturally.”

– David Bowie, Rock magazine, June 1974

The recording was later completed at Sigma Sound sometime between 20th – 25th November 1974, including the addition of overdubs. Mixed at Sound House, London.

Young Americans (stripped-down mix):

Same as previous track (above) but this version is a stripped-down mix, without some backing vocals and other overdubs.

After Today (version 2):

Recorded at Sigma Sound Studios, Philadelphia sometime between 8th – 23rd August 1974. Completion of this track was abandoned. Two versions of this song were recorded during the Young Americans sessions. The 1st version had faster tempo. The version that appears here is the 2nd of the two, which is more slow in tempo.

John, I’m Only Dancing (Again) (outtake):

Original working title: ‘I’m Only Dancin (She Turns me On)’, this is a complete reworking of David’s own ‘John, I’m Only Dancing’. Recorded at Sigma Sound Studios, Philadelphia sometime between 8th – 23rd August 1974. Recording was later completed at Sigma Sound sometime between 20th – 25th November 1974, including the addition of overdubs. Mixed at Sound House, London. This track is a completed outtake and was a high contender for the final running order of the album, but which would later be cut.

Never No Turnin’ Back (demo):

Recorded at Sigma Sound Studios, Philadelphia sometime between 8th – 23rd August 1974. Mixed at Record Plant, New York.

ROBIN CLARK: “We had ‘Takin’ it all the right way, keepin’ it in the back. Takin’ it all the right way, never no turnin’ back. Never need no’. And then that section comes in, ‘Wishing, wishing, sometimes. Doing it, up there. Nobody, nobody doin it. Getting it up’. That was so hard! David had like a puzzle. He brought this paper to us and he said ‘This is how I want you to sing this. It wasn’t just a straight sing it linearly and melodically. It was ‘I want it to jump in here and I want you to jump out there, and jump back in here’. That too was the first time I had seen anything like that in my life, but it was brilliant because he knew exactly what he wanted.”

AVA CHERRY: “Oh Lord it was too much! It was like ‘Man I’ll be glad when we’ve finished with this song!’.”

Two versions of this song were recorded during the Young Americans sessions. This is the 1st version (now regarded as a demo, although it was a completed track in it’s own right) recorded during initial sessions. However, a second version (which made it onto the album) was then recorded at Sigma later in 1974, and would be re-titled ‘Right’.

Right:

This is the complete and finished 1975 album cut, and the 2nd of the two versions, recorded in 1974 at Sigma Sound Studios, Philadelphia. Recording was later completed at Sigma Sound sometime between 20th – 25th November 1974, including the addition of overdubs.

It’s Gonna’ Be Me (outtake, without strings):

Original working title: ‘Come Back My Baby’. Recorded at Sigma Sound, Philadelphia, sometime between 8th – 23rd August 1974. Recording was later completed at Sigma Sound sometime between 20th – 25th November 1974, including the addition of overdubs. This is an unfinished mix and without the string section, which would later be added in January 1975.

It’s Gonna’ Be Me (outtake, with strings):

Same as previous track (above), but including string section which would later be added by Toni Visconti at Air Studios, London, on 12th January 1975. Mixed at Looking Glass Studios, New York. This track is a completed outtake and was a high contender for the final running order of the album, but which would later be cut.

Who Can I Be Now (outtake):

Recorded during initial sessions at Sigma Sound, Philadelphia, sometime between 8th – 23rd August 1974. Mixed at Sound House, London. Tony Visconti later booked into Air Studios, London, on 12th January 1975, at which point string arrangements were written and added to this and a number of other tracks. The version that appears here does not include the string section.

Somebody Up There (Likes Me) (unfinished mix):

Recorded at Sigma Sound Studios, Philadelphia sometime between 8th – 23rd August 1974. Mixed at Record Plant, New York. This track is a different mix and before final overdubs are added later in the year. This song is a progression from an earlier David Bowie composition ‘I Am Divine’, which was originally written for his aborted Nineteen Eighty-Four stage musical and recorded in December 1973 by The Astronettes.

Somebody Up There (Likes Me):

Same as previous track (above), but this mix is the completed and original 1975 album cut.

Take It In, Right (demo):

Recorded at Sigma Sound, Philadelphia, sometime between 8th – 23rd August 1974. This is the 1st version of the song to be recorded during these initial sessions, but later regarded as a finished demo (although a completed track in it’s own right) in favour of a 2nd version which would be recorded in November of the same year and re-titled ‘Can You Hear Me?’ for the Young Americans album. ‘Take It In, Right’ was first written in December 1973 by David and offered to Lulu. Although the track was recorded with Lulu during the Diamond Dogs sessions, that version still remains unreleased.

Can You Hear Me?:

This is the complete and finished 1975 album cut, and the 2nd of the two versions, recorded in 1974 at Sigma Sound Studios, Philadelphia. Recording was later completed at Sigma Sound sometime between 20th – 25th November 1974, including the addition of overdubs. Strings recorded and added at Air Studios, London on 12th January 1975. Mixed at Record Plant, New York.

Can You Hear Me? (striped-down mix):

Same as previous track (above), but this version is a stripped-down mix which doesn’t contain the backing vocals, string arrangement or other overdubs.

It’s Hard To be A Saint In The City:

Recorded at Sigma Sound Studios, Philadelphia, in November 1974. This is David’s cover of the Bruce Springsteen song. Tony Visconti arranged with top radio DJ Ed Sciaky at Philadelphia’s WMMR station for Springsteen to visit the studio in the very early hours of 25th November. David was initially keen for him to contribute to this track, but decided not to play it to Bruce at the last moment. The track remained unfinished until it was finally mixed and first issued by Ryko in 1989.

Funky Music (Is A Part Of Me):

This is Luther Vandross’ own original version. The backing singers are Anthony Hinton, Diane Sumler, Theresa V. Reed, Christine Wiltshire and Luther himself. It was recorded at Sigma Sound Studios in August 1974 and was the very same track which Bowie heard before re-writing it as ‘Fascination’ with Luther.

Fascination:

Recorded and mixed at Record Plant, New York, sometime during early to mid-December 1974. This is the completed and original 1975 album cut and David’s own cover of the Luther Vandross song.

Fascination (stripped-down mix):

Same as previous track (above), but this version is a stripped-down mix, leaving parts of the instrumental track and backing vocals remaining.

Fascination (alternative Ryko mix):

Same as David’s original 1975 album cut, but this is the alternative Ryko mix, differing somewhat from the original album version.

Win:

This is the completed and original 1975 album cut – the original working title ‘(All You Got To Do Is) Win’. Recorded and mixed at Record Plant, New York, sometime during early to mid-December 1974.

DAVID BOWIE: “This song is about winning. David Sanborn is on sax. He was experimenting with sound effects at the time and I’d rather hoped he would push further into that area, but he chose to become rich and famous instead. So he did win really, didn’t he?”

RADIO DJ ED SCIAKY: “[WIN] He’d sing three lines, then have the engineer play them back, keeping the first line every time. It was spectacular, watching him work like a painter, hitting every line the way he wanted. Around 7 a.m., Bowie asked the engineer to play the whole track from start to finish, twice. After the second listen, he nodded and said quietly, ‘That’s it. It’s done.'”

Win (alternative Ryko mix):

Same as previous track (above), but this is the alternative Ryko mix, differing somewhat from the original album version.

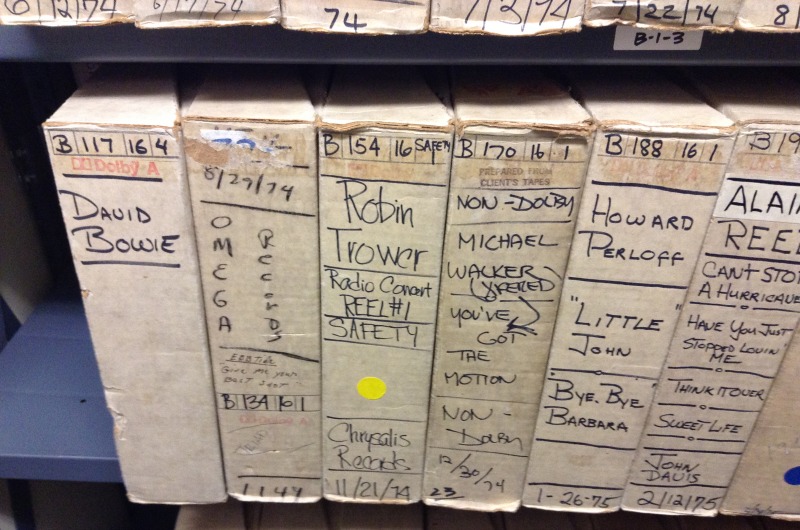

![original studio notes david-bowie-can-you-hear-me-call-9”></p><p><strong>E L E C T R I C L A D Y S E S S I O N S</p><p>ENGINEER HARRY MASLIN TAPE OPERATORS KEVIN HERRON & DAVID THOENER</strong></p><p> On 1st January 1975, work on the new album switched to New York’s Electric Lady Studios where David booked some studio session time. While he was there David wrote, developed and recorded ‘Fame’ – a song that had been adapted from ‘Footstompin’ – with Carlos Alomar, and recorded the Beatles song ‘Across The Universe’. David also invited John Lennon to play on both tracks. Both ‘Fame’ and ‘Across The Universe’ would later replace previously recorded Sigma Sound tracks ‘Who Can I Be Now’ and ‘It’s Gonna’ Be Me’, both of which had been on the album’s final short-listing. It’s also conjecturally reported that further unheard recordings were made during these sessions with John Lennon, including the American standard ‘Too Fat To Polka’ (or more commonly titled ‘You Can Have Her, I Don’t Want Her, She’s Too Fat For Me’) – the master tape of which is rumoured to have been ceremonially burned at the end of the session!</p><p><strong>Across The Universe</strong>:<br /> Recorded at Electric Lady Studios, New York, in January 1975. Mixed at Record Plant, New York. This is the completed and original 1975 album cut.</p><p><strong>Across The Universe (alternative and extended mix)</strong>:<br /> Same as previous track (above), but this is an alternative and extended mix, which includes the full ending without fade, together with some studio background chat from John Lennon cutting off at the end.</p><p><strong>Across The Universe (striped-down mix)</strong>:<br /> Again, same as previous track (above), but this version is a stripped-down mix with just David’s vocals, John Lennon’s guitar track and Willy Weeks’ bass.</p><p><strong>Fame</strong>:<br /> Recorded at Electric Lady Studios, New York, in January 1975. Mixed at Record Plant, New York. This is the completed and original 1975 album cut.</p><p><strong>Fame (instrumental backing track)</strong>:<br /> Same as previous track (above), but this is the completed instrumental backing track without all vocals.</p><p><strong>Fame (stripped-down mix)</strong>:<br /> This is a stripped-down mix, leaving just some of the instrumental pieces and more prominent vocals.</p><p><strong>Fame (stripped-down vocal only mix)</strong>:<br /> This is a stripped-down mix, leaving just David’s vocals.</p><p><strong>Fame (alternative “flute” mix, with full ending)</strong>:<br /> This alternative mix is thought by some to be a fake. However, this version is interesting because it includes a flute accompaniment throughout and David’s clearly-audible studio backchat at the very end, which is lacking from the album version and which a “fake” would not have. According to Toni Visconti, he reports: “I’ve heard about this flute recording before and someone asked me if John Lennon played it. Mary [Visconti’s wife] informs me that John couldn’t play flute. I don’t know any more about this version”.</p><p> Once Tony Visconti had completed mastering the tapes in London in January 1975, David then contacted Harry Maslin to mix the entire tapes again, including the newly-recorded Electric Lady tracks, but minus the now-titled ‘Young Americans’ track, which was by then in the hands of RCA and at the pressing plant ready for manufacture as a single. At the point were Harry Maslin took over, some extra recording of instruments and backing vocals were also made to some of the Sigma tracks later in January, with Maslin over-seeing production. It’s likely that the flute version of ‘Fame’ was also done at this late stage and therefore without Visconti’s knowledge.</p><p> – HARRY MASLIN –</p><p>~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~</p><p> In September 2009 a reel of tape was discovered for sale in a street market in Philadelphia. It appears to have come from one of David’s earlier recording sessions (dated 13th August 1974) at Sigma Sound Studios, Philadelphia, although how it ended up in a street market may never be certain.</p><p> What is known is that the majority of the tapes recorded during Sigma Sound Studios’ history has now become part of the Drexel University Audio Archive in Philadelphia, following the sale of the studios in 2003. So this may have been the source of the “stray” tape in question.</p><p> The tape – which is a 2″ multi-track recording – contains four songs in their early stages of rehearsal and recording. These tracks are<br /> <strong>‘Young American’ (takes 1, 2 and 3)</strong>, <strong>‘Lazer’ (take 1)</strong>, <strong>‘After Today’ (take 1)</strong> and <strong>‘Shilling The Rubes’ (take 1)</strong>. Up until the discovery of this tape, it was originally believed that ‘Shilling The Rubes’ was merely a working title for the album. However, its emergence on this tape now confirms that it is indeed a recorded song in its own right. In total there are 25 minutes worth of recording on the tape and according to the hand-written notes that came with the tape, there is reference to a 2nd reel.</p><p><strong>– THE NEWLY-DISCOVERED 2″ STUDIO REEL IN ITS ORIGINAL CARDBOARD BOX WITH STUDIO NOTES –</strong></p><p> Tony Visconti was contacted within days of the discovery of the tape. When asked for his thoughts on it, he said, “I think it’s a rough mix tape on quarter inch (just stereo), a work in progress. It’s rare to have four masters on a two inch reel. But then again it could be a back up tape. But it’s a great find for Shilling The Rubes alone. I don’t even remember how that goes!”</p><p> The tape was on offer on Ebay for a massive $15,000.00! However, the seller removed the item, but not before these 4 short samples of some of the tracks were circulated:</p><p><strong>Young American (take 3, demo sample)</strong></p><p><strong>Shilling The Rubes (take 1, demo sample)</strong></p><p><strong>Lazer (take 1, demo sample)</strong></p><p><strong>After Today (version 1, take 1, demo sample)</strong></p><p> <img decoding=](https://www.davidbowieworld.nl/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/david-bowie-can-you-hear-me-call-9.jpg)

– ORIGINAL STUDIO NOTES WHICH WERE INCLUDED WITH THE TAPE –

Only time will tell if the full versions of these tracks become available. It was said that a second reel from the same session with three additional songs and never-heard-before takes was to be sold at a later date.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Special Thanks The Year of the Diamond Dogs

HOW DID DREXEL END UP WITH RARE DAVID BOWIE RECORDINGS?

Drexel houses part of legendary rocker David Bowie’s five-decade career in the basement of University Crossings. Photo by Adam Bielawski

The “David Bowie Is” retrospective exhibit newly opened at the Chicago Museum of Modern Art is full of gems from the rock performer’s archives —handwritten lyrics, original costumes and album artwork that the legendary musician donated for all to see. But there’s one tiny part of Bowie’s five-decade legacy that is currently inconspicuously shelved in a basement of a building on Drexel’s campus.

From August to November of 1974, Bowie recorded part of his ninth studio album, “Young Americans,” at Philadephia’s Sigma Sound Studios. But only one tape from the sessions remained in the studio’s archive when its 6,200 master tapes were donated to Drexel in 2005. Now the tape is part of the Sigma Sound Studios Collection in the Drexel University Audio Archives, housed in the basement of University Crossings.

The assortment of tapes helps tell the story of Philly music from just before the founding of the studio (in 1968) to 1996, when Sigma switched from using analog tapes to digital recording. In the early ‘70s, the studio was known for producing Philly soul and “The Sound of Philadelphia,” and Bowie, who was known for his glam rock albums and personas, was looking for a change.

“Imagine it’s 1974. Sigma was hot. Coming out of Philly and coming out of Sigma was hit record after hit record,” said Toby Seay, project director of the Audio Archives and an associate professor in the Westphal College of Media Arts & Design. “It would be very enticing for an artist like Bowie to say, ‘Let’s go there and see if some of that ‘magic’ wears off.’”

Drexel’s Toby Seay

Toby Seay, project director of Drexel’s Audio Archives and an associate professor in the Westphal College, happily shows off “Reel 4.”

The session’s remaining 16-track tape, dated August 14, 1974, and labeled “Reel 4,” contains just five songs. These include alternate takes of songs that made the album, like reworked versions of the title track, and rejected songs that only appear on reissues, like “John, I’m Only Dancing (Again),” “It’s Gonna Be Me” and “Who Can I Be Now.” The single sheet of paper accompanying the tape only lists the tracks, takes, times and instruments used — no dates, no musician names and no inventory of its place alongside other possible tapes from the Bowie sessions.

Of course, the album is far from unknown. “Young Americans” reached the Top 10 List in America and the song “Fame,” which was later co-written and featured vocals from John Lennon in New York City, was Bowie’s first No. 1 single in America. But the records from the smash hit are less prominent.

“Bowie had the forethought from the very beginning to own his recordings. That’s so rare,” said Seay. “From what I understand, he knows where every tape of every record he’s recorded exists except for “Young Americans’ and ‘Station to Station.’”

The whereabouts of reels 1, 2, 3 and any possible recordings after reel 4 were unknown when Seay first started cataloging the collection. But that all changed when he discovered a seemingly inconsequential tape labeled “DB.” Upon listening, he realized it was actually a recording of a studio session in which “DB,” or “David Bowie,” and his musicians are heard chatting, going over song parts, and practicing “Who Can I Be Now” and “John, I’m Only Dancing (Again).”

“I don’t know what enticed me to pull it off the shelf, but something did. And since then, I’ve looked for other tapes that might be labeled that and there aren’t any,” Seay said.

Reel 4 of the “Young American” sessions.

Reel 4 of the “Young American” sessions.

At one point during the hour-long recording, Bowie asks backup singer Luther Vandross, who later won eight Grammy Awards for his solo career, to come in stronger on the “Who” in “Who Can I be Now.” After demonstrating the kind of vocal he wanted, Bowie self-deprecatingly tells Vandross, “I mean, I’m not as good as you, but you know what I mean.”

“I don’t know how illicit this was, but somebody just rolled a reel of tape in the studio while they were working,” Seay said. “Even though they’re making music in a studio, after a while you get that it’s just people doing their job.”

It’s a revealing look into Bowie’s creative process, and the sessions as a whole. Additional insight into the sessions became clearer once Seay received copies of reels 1 and 2 — on behalf of Bowie himself.

Several years ago, Bowie discovered the tapes on ebay and arranged for the sender to give them to him. But first they were sent to Seay to be digitized, since he had previously sent Bowie the digital copies of the fourth reel. In exchange, Drexel kept digital copies of the newly discovered reels — so those recordings can only be found only in Bowie’s personal collection and Drexel’s collection.

Those tapes include other versions of songs heard on reel 4 and the secret recording, but there are also some surprises. Two tracks, “Lazer” and “Shilling the Rubes,” have never been released on any Bowie compilation or album.

While the physical Bowie tape is an important, and notable, part of the collection, and the “plastic soul” Bowie recorded was influenced by Philly soul, the collection has many other tapes from local artists and producers that round out the archive’s historical and cultural significance. Even though Bowie recorded in the Philly studio, he brought in New York studio sessions players and his producer, instead of using the Sigma Sound engineers and musicians.

Unfortunately, all of the Bowie tracks, and the thousands of others in the collection, can’t be put online by Drexel, which owns the physical rights, rather than the copyrights, on the tapes. Instead, Seay is working on a digital database of the tapes so people know what they can listen to at the studio, though it’s an arduous process involving digitizing and cataloging works.

Besides Bowie, there are tapes from Patti LaBelle, Teddy Pendergrass, Gladys Knight and many other artists. Who knows just what other treasures are hiding in the archives?

=================================

David Bowie’s Young Americans – Philly weekly

David Bowie recorded his Philly pop-soul in 1974,. The “Sigma Kids” were with him then, and they’ll be with him again next week when he comes to town.

Marla Kanevsky can’t remember who made the first call this year, but when the phone rang she got that same old feeling.

“I always think next time I won’t do it,” she says. “I won’t get so excited. I won’t start obsessing. But then Patti or Leslie are on the phone and it’s the same thing all over again–David Bowie’s going on tour. Nothing else matters.”

She laughs, because now other things do matter. But the announcement of an impending Bowie concert still holds the power to tear her in two. She remembers an August night in 1974 when Bowie invited her to a party! The night David Bowie held her hand! And she wonders if this year she will finally meet him as an adult, as an equal, as a 43-year-old mom.

“I’ve met him, I think, seven times since 1974,” she says. “And I always yell out, ‘David, I’m a Sigma Kid!’ even though I realize how pathetic that sounds. And if he talks to us, I am always just like, ‘Can I take your picture, David? Can I have your autograph?’ It’s embarrassing.”

Nearly 30 years later, Marla Kanevsky is still a fan. Not an ordinary fan–a super fan. “He has been there through it all,” she says. “The death of my parents, the birth of my son, my husband’s accident. Everything.”

Just talking about all this reduces Kanevsky–or elevates her, if you’re of such a mind–to tears. “I am such a wimp!” she hollers.

Oh, but she is so much more. She’s much more than a Sigma Kid, too, though once you know her story it’s easy to see why she still identifies herself as that 16-year-old girl from Lower Merion. To this day the Sigma Kids can lay claim to perhaps the most beautiful and bizarre fan-star interaction in rock ‘n’ roll history.

The Sigma Kids didn’t just meet David Bowie. For one night they were his confidantes, his buds–underage kids for whom he bought wine and champagne! And fresh corned beef sandwiches! Sandwiches they were too nervous to eat! Yeah, and he played Young Americans for them–straight from the master tape–before RCA’s label execs heard it and certainly before you heard it. You who weren’t there to hear Bowie debut his version of the Philly Soul sound.

But here it is, as best it can be laid down, given the smoke and white powder and years that obscure this tale: the Sigma sessions and the Sigma Kids, a story that ends with Marla Kanevsky’s entire superfan life.

Camping out for tickets seems like no big deal these days, but the Sigma Kids raised it to unparalleled heights.

They spent two weeks straight sleeping in the streets so they could do things like watch Bowie walk from the Barclay on Rittenhouse Square to his limo. Then they’d dash off to their cars, driving as fast as they could to reach Sigma Sound Studios before he got there.

“If he was already out of his limo when we were pulling up,” remembers Patti Brett, “we would stop our cars in the middle of the street, get out and halt traffic just to say ‘Hi’ to him again.”

Over time the Kids got friendly with the studio staff and the Bowie entourage, especially guitarist Carlos Alomar. Sometimes Bowie would chat with them.

He eventually learned their names: Marla, Patti, Leslie, Purple–about a dozen in all. No one remembers who made the announcement that Bowie had decided to throw a party for them when the sessions wrapped.

What they do remember is that they were led into the studio late at night, their hearts thudding in their chests.

Dagmar, a one-named rock photographer, documented the party. She remembers Marla Kanevsky because she was “a pretty little girl, and very emotional. You could see it was a very deep experience for her. She held Bowie’s hand for a while. When he let go, she held hands with her friends.”

Kanevsky herself doesn’t remember much, except asking Bowie to marry her. “It’s awful, isn’t it? So cliche, but I think that’s why I said it. It seemed like what I should say. He said something like, ‘You’ll have to speak to my wife about that, love.'”

For Bowie the night met two objectives: He got to reward some devoted fans, and he had a test audience for his new sonic experiment. The artist formerly known as Ziggy Stardust, the bisexual space alien rock star, had completed his transformation to white soul singer. These kids were his first listeners.

At the party, he sat down in the back of the studio and bit his nails. No one spoke while the album played. But after the last note sounded one of the Kids yelled, “Play it again!” That broke the ice.

The Kids got up and danced. Bowie did the bump.

Bowie’s approximation of the Philly Soul sound broke him commercially. He ascended from the 3,000-seat Tower Theater in July 1974 to the 16,000-seat Spectrum in ’75.

That’s where stories about the Sigma Kids usually end, but their lives went on long after the party was over.

Three decades later, the Sigma Kids arrive at Doobie’s at 22nd and Lombard to down a few brews and reminisce. Patti Brett, a Sigma Kid who has run Doobie’s for her mom since 1985, jams a bunch of tables together. A big, brassy blond, she changes from her work clothes into a black dress, lets her hair down and stands resplendent in bawdy maiden chic.

It’s a happy night, complete with a special guest star. Carlos Alomar, David Bowie’s long-time right-hand man, is taking a night train from New York. While the Kids have interacted with Bowie only on rare occasions since 1974, most of them hurried, Alomar has become a friend.

Before everyone else arrives, Brett and Leslie Radowill, both 46, look at pictures of Bowie going in and out of the studio in a variety of funky berets and glasses, flared trousers and shirts that billow around his skeletal frame. But they remember little in the way of specifics.

“It’s frustrating,” says Brett.

“Well, we smoked a lot of pot–and I know what pot does to brain cells,” replies Radowill.

Not long afterward, Marla Kanevsky arrives with her emotions in tow. A pretty woman in the midst of the Weight Watchers program, she has shed about 30 pounds. Still she hides her face behind big dollops of brown hair and keeps her sunglasses on indoors.

She brings a journal describing the Sigma Studio experience and a sweet, strange petition she circulated in 1975 urging the singer to stop using drugs. The teenager wrote of the physical “ch-ch-ch-changes” Bowie had gone through that year, his cocaine-fueled drop to a reportedly corpse-like 80 pounds.

“Remember I was just 16,” she says. “I was a kid.”

Then she cries for a moment, right there at the table.

Life has not been terribly kind to Kanevsky. In 1979 doctors discovered that her mother’s back pain was evidence of a cancer that eventually killed her. (Lodger was the icy Bowie album of the moment.) About a year later, her father–who owned A&H Food Distributor in West Philadelphia–died from a massive heart attack. (The album was, fittingly, Scary Monsters.)

Her future husband Paul–also a Bowie fan–supported her throughout these ordeals. Together they tried opening a deli, but the business failed and they lost most of the insurance money they had received from her parents’ deaths.

In 1991, when Bowie came to the Tower with his then-band Tin Machine, Paul got into a car accident before the show. He seemed unhurt, but the next day he went to a doctor. Almost a dozen years later he walks with a cane and can’t stand for long periods of time, making it impossible to pursue his career as a chef.

Kanevsky and her husband have a child, Zane, now 14, who is named after a lyric from Bowie’s “All the Madmen.”

“I always said I would pop a kid out and sit him in front of a speaker,” she says. “That’s pretty much what happened.”

Kanevsky works as a teacher’s assistant in Mays Landing, N.J., where she lives. The family scrapes by on her meager salary and Paul’s disability checks.

Of the dozen or so people invited into the studio that August night, only Kanevsky, Radowill and Brett continue to orbit, as a group, around Bowie. Phone calls among them–sporadic between albums–surge when the singer hits the road. They see far fewer shows than they used to, and they don’t camp out for seats anymore. They’ll see the local shows and maybe catch a gig in New York, but that’s it.

They have adult responsibilities. Radowill is unmarried and childless but tends to an elderly father. Brett got married a few years ago and has two stepchildren.

Still, some things don’t change.

At one point Brett announces she’s won a seat in a raffle to see Bowie perform on A&E’s Live by Request, a two-hour TV concert.

“I’m sorry,” she says. “I didn’t want to make anyone jealous.”

“Oh no,” Radowill and Kanevsky respond in forced tones. “Have a great time!”

(A week later Kanevsky gets on the phone and confesses her jealousy. “I feel so out of the loop,” she says.)

With Bowie back on tour, it seems a time of confession for Kanevsky. She says her Bowie fandom feels like an addiction–confesses that she loves her family and her job, yet something is missing.

She cries–a lot. But she doesn’t seem like a woman on the verge of a nervous breakdown. Rather, she seems nervous about a breakthrough.

“I have attended about 75 concerts, and what has it gotten me?” she asks. “I had a good time, but for some reason I always expected more.”

Soon Alomar arrives in a bright summery shirt, like an arpeggio in cotton, and the troops head outside for an impromptu photo session. Kanevsky tries to hide in the back, her head bobbing above a sea of shoulders like a swimmer risen from the depths. She’s lost a lot of weight, but she doesn’t see it.

Carlos Alomar served as Bowie’s guitarist from 1974 to 1987, toured with him again in 1995 and plays on one track from Bowie’s current disc, Heathen.

He says he thought the Sigma Kids’ behavior was a little weird at first. But the Kids told him they wanted to be close to David, and Alomar helped. He used Radowill’s Instamatic to take photographs inside the studio, smuggled out tapes of the day’s sessions and even invited them back to his hotel room where he and his wife, backup singer Robin Clark, became friends with this curious assemblage of young Americans.

As Bowie moved from the tuneful but meat ‘n’ potatoes rock of the Ziggy years, his new rhythm guitarist–who had played with James Brown–was his connection to the music that would help his soul experiment work.

Alomar says he still hangs out with the Kids on occasion because they are “campy, silly and fun.”

“Usually, people who sleep in front of a studio–it’s about fucking,” he says. “But with them it was about devotion.”

Though the Kids clearly had crushes on Bowie, there was no Sigma sex that August–only fidelity.

Brett has the ticket stubs to the more than 120 Bowie concerts she’s attended. She lost two jobs while following Bowie on tour, one as recently as 1995, but she’ll tell you–with conviction–that it was worth it. “This is the choice we made,” she says.

Radowill raises more profound questions: “How would my life be different if I wasn’t a David Bowie fan?” she asks. “Would I be married? Would I have children? Would I have gone to college?”

A story like this, which deals in behavior bordering on the obsessive, must necessarily include some words from a psychiatrist. Those words are coming. But that doesn’t mean something very powerful didn’t occur in 1974, something that was felt both inside and outside the studio.

Former WMMR DJ Ed Sciaky watched Bowie record “Win” for Young Americans at Sigma.

“He’d sing three lines, then have the engineer play them back, keeping the first line every time,” says Sciaky. “It was spectacular, watching him work like a painter, hitting every line the way he wanted.”

Around 7 a.m., Bowie asked the engineer to play the whole track from start to finish, twice. After the second listen, he nodded and said quietly, “That’s it. It’s done.”

As if on cue, the Kids outside started applauding–hooting and hollering up at the studio windows.

“It was eerie,” says Sciaky. “I don’t know how they could have heard any of the music, let alone responded to what Bowie said. It was probably some kind of coincidence, but it felt like they knew, they heard, they were connected. Bowie looked stunned.”

Bowie has often told interviewers that he retains only fragmentary memories of 1974, ’75 and ’76, his cocaine years. When he returned to Sigma for a radio special in 1997, he signed his gold Young Americans album: “With fondest memories (I would imagine), David Bowie.”

The night that made local legends of the Sigma Kids may have left only small, residual traces in their idol’s memory. But the Kids mean enough to Bowie that when Alomar arranged an impromptu reunion in 1995, the singer hung around even when his handlers tried to get him to leave.

The meeting occurred in a tented area just behind the stage of Bowie’s Outside tour. The singer joked with them about their advancing ages. Brett grabbed Bowie’s graying goatee and said, “You’ve gotten a little older yourself there, mister.”

It was a wonderful moment–the walls torn down, the star Brett once worshipped now a person just like her and just as ripe for ridicule. Kanevsky couldn’t believe Brett said it, though, and yelled at her to stop.

“Marla!” Brett replied. “He’s a person.”

Marla Kanevsky earns just under $11,000 a year as a paraprofessional assisting five- and six-year-olds with disabilities, both mental and physical, sometimes in basic tasks like going to the bathroom.

“She’s got the most unbelievable patience,” says her co-worker Kathy Watkins. “Some of these kids act out all day long, and Marla soothes them and gets them focused. She’s the best of us.”

Kanevsky’s colleagues encourage her to attend college. The district would reimburse her for classes, but it’s a no-go. The confidence isn’t there. She tried photography school, but it didn’t stick. Her work life has included a series of casino jobs, including cage cashier.

Between class hours and before- and after-school day care, Kanevsky works from 7 a.m. to 6:15 p.m., five days a week. Often she brings in photographs from the Sigma sessions and her more recent Bowie meetings. She has plenty of them. At the reunion in 1995 Bowie got down on one knee and sang the “Zane, Zane, Zane” refrain from “All the Madmen” to her son. But all she could think to do was ask for another autograph, another picture.

When Bowie started his Internet service, Bowienet, he assumed the screen name “Sailor” and sometimes even responded to Kanevsky’s missives. She thanked him for a brief meeting outside a 2000 New York City gig; he said it was his pleasure. She invited him to Zane’s bar mitzvah.

“How sweet of you,” he wrote. “Can’t make it but what a lovely thought.”

Her husband’s back injury has made it easier for Kanevsky to sit closer to Bowie when he’s on stage. They are often able to score early admittance and special seating for Bowie’s general admission shows. But as she says through still more tears, “I just know the other fans think we’re trying to get over, but I would never see Bowie again if it meant my husband wouldn’t have to be in pain.”

David Bowie might seem like a small thing to give up, but not for Marla Kanevsky. That she can even conceive such a thing may mean she’s finally shedding the role of Sigma Kid after all these years. At one point she even throws down the gauntlet and asks if a reporter can find out why she’s devoted so much of her time and energy to the pursuit of David Bowie.

Dr. David Roat, a psychiatrist on Penn’s faculty, says that when someone has a seminal event in life, like the Kids at Sigma did, “Energy may remain tied up in it. Whenever things go badly, they return there. It’s similar to post-traumatic stress disorder, but they become fixated on a good experience.”

Losing her parents so soon after the event may have sent Kanevsky spiraling backward, to Sigma and to a time when the world seemed filled with limitless possibilities. Continued personal and financial troubles kept her there.

Roat says Kanevsky’s capacity to show regret signals that she may be closer to embracing her life. He even says that continued attempts to get Bowie’s attention may be a good sign.

“When someone has a powerful experience before they are old enough to process it, they might try to repeat it in some more controllable way. It’s an attempt to gain some kind of mastery. For her to finally have a real conversation with Bowie outside the fan-star dynamic might be the best thing for her. She might finally be able to put him on the shelf where he belongs, shed her adolescence and get on with her life.”

Kanevsky’s life is perhaps not so bad as her tears suggest. Last month, before she went home to celebrate her son’s graduation, she took part in the school’s yearly class picture ritual.

One child, Jamie, has a condition called Fragile X syndrome. The slightest change in his routine, like a photograph session with his teachers, brings on tears and panicked, downcast eyes.

Kanevsky approached Jamie, knelt in front of him, touched his shoulders and spoke in a soft, soothing voice.

“We’ve had that child in school for a few years now,” says Maureen Minton, another co-worker. “That’s the first picture we ever got where he smiled and looked into the camera. It was Marla. She’s such a wonderful person, but she doesn’t always see the beauty in herself.”

Once Kanevsky calmed the child she performed her usual maneuver: She stood in the back and hid her body.

“I don’t know what I expect from Bowie,” she says later. “But just once I would like to meet him and have some conversation other than ‘You’re so great.’ I want to speak to him like an adult. And I think I’m ready. After all these years I believe I could finally have a mature meeting with him.”

Ironically, the album that emerged from Bowie’s obsession features no Philadelphia musicians. Michael Tarsia of Sigma Sound Studios remembers one bassist saying he wasn’t going to “give this skinny white kid” his sound. So Bowie drafted what was then considered the “B” team, lucking into Carlos Alomar, a then-unknown Luther Vandross and saxophonist David Sanborn.

But Bowie brought his own vocals to record, and most were laid down in one take. For all of Ziggy’s charisma, he sounded nasal and thin. On Young Americans, Bowie showcased a range that encompassed both dusky baritone and creamy falsetto.

“Right” and “Fascination” offer slippery funk, and the title track soars over the boundary separating gritty soul from Beatles-styled pop. But it’s the slow stuff where Bowie really gets down to cases.

“Can You Hear Me” stands among his best ballads ever. And “Somebody up There Likes Me” would raise a sweat on any singer’s neck, whether he be Al Green or Daryl Hall.

The album the Sigma Kids first heard was very different than what Bowie released. “Fame” and “Across the Universe” were recorded later in an impromptu session in New York with John Lennon that bumped out a couple of sweeping, romantic gems.

At some point Bowie got it in his head to pitch Young Americans to the press as “plastic soul” ,a tag that revealed more about his own insecurities than it did about the music he’d made. In fact, he became the first white artist to perform on Soul Train–just one odd highlight in a spectacularly strange career.