Visconti recounts the making of David’s The Man Who Sold the World

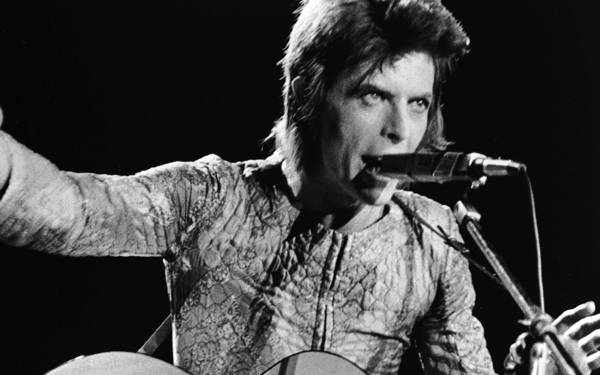

By Mark McStea (guitarworld.com) (Image credit: Michael Putland/Getty Images)

50 years on from its release, the former David Bowie bassist and uber-producer tells the story of one of Bowie’s greatest albums, and the enduring influence of Mick Ronson

David Bowie’s third album, The Man Who Sold the World, was released in the U.S. in November 1970, before getting its release in Bowie’s homeland (the U.K., of course) in April 1971.

It marked a notable change in Bowie’s songwriting and musical direction, featuring hard-rocking riffs and extended guitar heroics from legendary axeman Mick Ronson, and seemed to be the stepping stone between the “hippy folkie” Bowie and the glam-rock god.

Ronson became Bowie’s essential sonic and visual foil, and his influence extended beyond the first flush of glam rock into punk and metal, both American and British. Randy Rhoads saw Ronson playing live with Bowie in Santa Monica in 1972 and borrowed his choice of guitar and haircut from Ronno. Cult guitarist Billy Duffy has often cited Ronson as his primary influence.

Mick insisted from the beginning of the album, ‘If we’re going to play in the same band, you’d better listen to Jack Bruce.’ I did, and I think I rose to the occasion

Ronson went on to a solo career after Bowie disbanded the Spiders from Mars in 1973, and also performed with Bob Dylan and Ian Hunter before his untimely death from cancer in 1993. (Ronson fans should check out the box set Only After Dark, released late last year). TMWSTW was produced by Tony Visconti, who also played bass with Bowie at that time.

To mark the 50th anniversary of its release, Visconti was happy to discuss the making of the album and the challenges of recreating it live in its entirety in his current band, Holy Holy, which, incidentally, features former Spider from Mars Woody Woodmansey on drums.

The Man Who Sold the World marked a shift in direction to a harder, rockier sound. You were playing bass with Bowie at the time. What influenced his change in direction?

“We felt we had had enough with the folk-rock influence of the Space Oddity album. Since all those songs were written on his acoustic 12-string, it had a gentler sound overall. We had met Mick Ronson during the mixing sessions, and we were very impressed with him. He was one of the clappers on Wild Eyed Boy from Freecloud during the mix session. We wanted the next one to sound a lot tougher and more experimental.“

What did Mick Ronson bring in terms of that tougher approach?

“He really loved Cream and extolled their virtues. We heard some of his work with the Rats [the band he was in prior to hooking up with Bowie], via drummer John Cambridge of Junior’s Eyes.

“John was actually up for TMWSTW then Mick told us all about Woody Woodmansey, who got the job as drummer. Mick insisted from the beginning of the album, ‘If we’re going to play in the same band, you’d better listen to Jack Bruce.’ I did, and I think I rose to the occasion.

Can you remember what gear Ronson was using?

“He had a black Les Paul Custom – his only guitar, as far as I know. When he came to live with us – me, David and his wife Angie, in Haddon Hall, in Beckenham – all of us took turns sanding down my Strat and staining it clear. He wanted us to do the same with his Les Paul. We all took turns — John Cambridge, Bowie, me and Roger, our roadie.

“He had a Marshall head and a 4×10 cabinet. I don’t remember the name of the head, but it had three knobs, volume, treble and bass [presumably the Marshall 200 Major, 200-watt head often referred to as The Pig]. He always had the three knobs set to 10. He would control the volume with his guitar volume. He also had a wah-wah pedal that he used in fixed positions for mid-range boost.“

David was open to input and band camaraderie. He welcomed any influence, and Ronson was usually the one who steered him to write heavier songs

Was Bowie very open to suggestions? Was he fairly rigid on his original conception or was there much room for maneuvering?

“The songs came in all sorts of ways. After All was written on his 12-string, as was part one of The Width of a Circle, then the heavier tracks were kind of written by all of us, but Bowie got full writing credit. Nowadays, of course, everyone in the band gets writing credits. Back then we were expected to consider ourselves as arrangers of our own parts. Historically, that’s the way it was until David worked with Carlos Alomar.

“Carlos wrote the riff for Fame and got a writer’s credit. For TMWSTW we did the same thing but never got the writing credit. As we were all living under the same roof during the making of the album, David was open to input and band camaraderie. He welcomed any influence, and Ronson was usually the one who steered him to write heavier songs.

What was Bowie’s work rate like during the recording? Was he a perfectionist, an experimenter?

“When he was hot, he was really hot. Hands on, full of ideas. He was often slack, too, spending hours in the studio lounge planning home decorations with Angie Bowie. So Mick, Woody and I were left for long periods to work out the band parts for his songs.

“He was very enthusiastic when it was overdub time, again, full of ideas and open to ideas. Since he, Mick and I were very competent singers, David particularly liked the backing vocals I came up with. I have fond memories of singing them around one mic.“

When David was hot, he was really hot. Hands on, full of ideas

Your bassline on The Man Who Sold The World – the song – is very melodic to the point that you could identify the song purely from the bassline.

“Well, as I said, we wrote our own parts. Mick came up with his. I put the running scales in the chorus because the melody and lyrics were so sparse, ‘Who knows, not me,’ I played 16 notes under those four words alone.“

The actual riff for The Man Who Sold The World is cunningly simple, yet complex in its ability to sit over the shifting chords. Was that kind of compositional idea instinctive rather than something that was thought out theoretically?

”Mick and I worked our parts out against David’s simple chord structure. Mick doubled my bass part for the choruses. We were into the simplicity of the song and didn’t want to add too much to it. For the record, it was an eight-track recording so there was no room left to add more anyway. The limitations of tracks in those days made musicians think more creatively rather than leaving it all to the mix.“

The Width of a Circle has great soloing from Ronson. It’s quite a long track. Was it conceived that way or was that just a product of going with Ronson’s flow?

“Part one existed first and tried out in The Three Tuns, our local pub. When we recorded it, we felt it should go on a bit, though. I think David played that interlude section live, but changed it up all the time. It didn’t get organized to the chords you hear on the record until the actual session. That’s where the song could’ve ended, but then we started to jam part three.

“It was a long day, but finally we knew we had something great and played the entire long version by the end of the night. Our band setup was Woody’s kit on a riser and Mick’s and my amps on either side. David was in an isolation vocal booth with his 12-string. We had to do a lot of fixes, but it is essentially a live recording.

The limitations of tracks in those days made musicians think more creatively rather than leaving it all to the mix

“The hardest thing was getting the reverse echo happening on the middle part on David’s guitar, playing the song backwards and adding the reverb on another track. Then flipping the tape back over and hearing the reverb come before the chord. It involved a lot of trial and error.

“Needless to say, you can do that in Pro Tools in five minutes today. I think Ronson’s solos are live, maybe with a fix here and there. That multi-track has been lost, so I can’t really tell more about the session today. All the Madmen is almost like three songs joined together.“

Black Country Rock was a jam. We actually ran out of songs, so Mick, Woody, David and I started jamming to Woody’s beat. David put the words together and wrote the lyrics in about 15 minutes

How fully formed was it at the recording stage?

“All the Madmen was done in three distinct parts – and I do have the multi-track. I’ve remixed most of TMWSTW recently [a 50th-anniversary reissue is scheduled for late 2020] and realized the three sections were mixed separately, and we couldn’t hear how the parts fit together until they were joined up on two-track tape.

”If you listen closely you can hear the edit into part three because the reverb cuts off. With the new remix I put the three sections together in Pro Tools and the overlaps are all seamless. It sounds more natural.”

How did Black Country Rock come together? It almost has a Zep-like feel.

“Black Country Rock was a jam. We actually ran out of songs, so Mick, Woody, David and I started jamming to Woody’s beat. At some point we started rolling tape and listened to our efforts. It defied description. We realized it was part funk, country and rock. David put the words together and wrote the lyrics in about 15 minutes after we organized the chord changes and structure.“

She Shook Me Cold has a really heavy, doom-laden riff, not unlike Black Sabbath. The bass is very prominent on this track. Was this the Ronson request to “play like Jack Bruce” in action?

“David came up with the idea on his 12-string. It wasn’t as heavy at first. Then Mick took over by playing it as power chords. I played around the chords coming up with my bass line.

“Then the song started to take shape. We tried recording it straight through but could never get out of the first part into the guitar solo. So we actually recorded it in two sections.

“We held the long chord just before the guitar solo. Once we had a good take, we proceeded to record from the guitar solo into the last vocal section. Again, listen closely and you’ll hear the two-track edit. We, Holy Holy, kick the shit out of that song live. The crowd goes wild for it.“

When you look back at the album now, recorded without all the aids of modern technology, are you happy with how it turned out, or would you have done anything differently in hindsight?

The mixing could have been better, but we ran out of money. The label was crying for it to end

“I admire how hard we all worked to make great live takes and make very modern music. We were among the very first to use the big Moog synth very creatively with a lovely classical pianist, Ralph Mace. Both Mick and I wrote arrangements for him to play, one part at a time.

“We used some tricks like tape phasing and flanging, razor blade edits, and the 16-track, 2-inch tape machine, which was sheer luxury. The mixing could have been better, but we ran out of money.

“The label was crying for it to end and we had spent at least five-weeks in the studio, which was a very big deal back then. We wanted to make ‘our Sgt. Pepper’ after we learned the Beatles had spent almost nine months making that album. ‘Our Sgt. Pepper’ was a running joke after that – when David and I started a new album.”

In Holy Holy, you play a lot of the early Bowie catalog, including TMWSTW in its entirety. What are the challenges?

”TMWSTW is a very complicated album and very heavy for its time. Since it was very experimental, we were pushing the boundaries and a lot of it was improvised. Some of those songs I never played again after they were recorded. The title track is a standard, so I played that many times in tribute shows over the years.

Ronson only revealed very casually that he took piano lessons as a boy, but you can hear from his arrangements that he understood very sound music theory from those lessons

”But The Width of a Circle was never played again in that form after it was recorded, by me or anyone else. David did a very watered-down version on some Ziggy tours. I had to write out all my bass parts and put them in primer form. For three or four months before the first Holy Holy gig I played the whole show every night, page by page, until it was memorized.

”It took both of our guitar players, James Stevenson and Paul Cuddeford, doing a similar amount of woodshedding and then meeting up and planning who would play lead and lead harmony. Mick was almost always multi-tracked on the album.”

Finally, you worked with Bowie at many different times over the years. It’s a difficult question, of course, but where would you rate Mick Ronson in the guitar hierarchy?

“Ronson is right at the top for me. On this album we were only getting a taste of things to come. He only revealed very casually that he took piano lessons as a boy, but you can hear from his arrangements that he understood very sound music theory from those lessons. He also knocked me out with his string arrangement on Life on Mars? The more confident Ronson became with us, the more experimental he got. Years later, he was at the very top of ‘guitar hero’ lists.”

The 50th Anniversary edition of The Man Who Sold the World is out now via Parlophone (November 2020)