The way the singer overcame family abuse has much to teach us, says child psychologist Oliver James

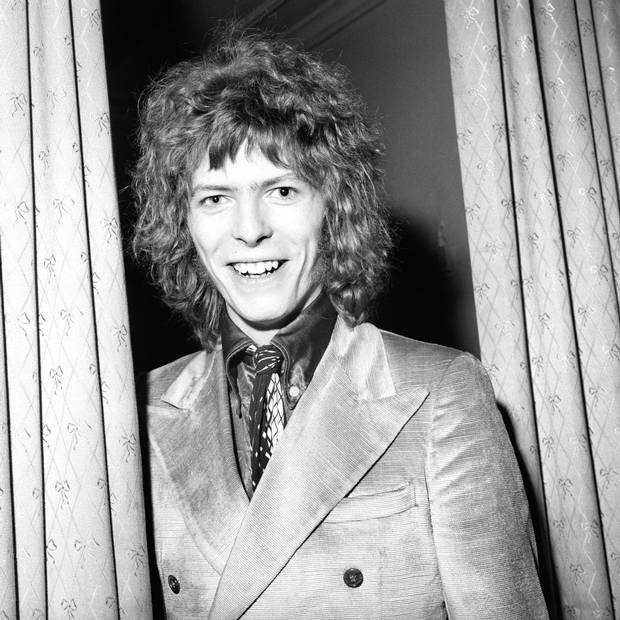

I began researching David Bowie’s childhood three years before his death in January this year. As you might expect of such a remarkable man, it’s a remarkable story, one with much to teach us.

Madness was the refrain playing in his family background: three of his mother’s sisters reportedly became psychotic, likewise Terry, the half-brother he dearly loved.

Their insanity, and Bowie’s fear of it, became a major theme of the lyrics of his greatest albums.

You have to go back a generation to understand what made Bowie tick. His maternal grandmother, Margaret Burns, was a cruel woman. His own mother, Peggy, was the oldest of Margaret’s six children. In 1935, aged 22, Peggy was strikingly good-looking and modelling lingerie. Having met a glamorous French barman, she became pregnant and gave birth to Terry. Soon afterwards, the Lothario left.

Margaret looked after Terry from the age of six months. But the stigma of illegitimacy was humiliating. In passing her son to Margaret, Peggy had unwittingly created a natural experiment: Terry was raised by a woman who reportedly nurtured three psychotic daughters; Bowie got a subtly different deal.

Margaret was emotionally abusive to Terry. Rebuked by her for some misdemeanour, he smirked out of nervousness. Margaret said “go on, laugh again”, and he nervously did so. She smacked him across the ear and said, “that’ll teach you to laugh at me”. Such abuse is the single strongest childhood predictor of schizophrenia – more so, even, than sexual abuse.

Peggy married Haywood ‘John’ Stenton Jones in 1946 and gave birth to David the next year. John was affectionate to his son. He took him to pop concerts and bought Bowie a saxophone when he was nine years old.

Terry joined the family when he was aged nine, shortly after Bowie’s birth.

John knew all too well that Peggy still regarded the French barman as the love of her life, and victimised Terry in direct proportion to his favouritism of Bowie.

In 1967, the cumulative effects of emotional abuse, being unwanted and feeling stigmatised resulted in Terry’s first psychotic episode. He saw a blinding white light and claimed that Jesus Christ appeared, telling him he had been picked for a special mission.

This incident was to be immortalised in the line “a crack in the sky and a hand pointing down at me” in Bowie’s song All You Pretty Things. Terry spent the rest of his life in and out of mental hospitals until, in 1985, he threw himself under a train.

Bowie often wondered why he was chosen for greatness and Terry for madness, and wrote of his fear of mental illness in many of his songs. While his brother’s childhood was a textbook case of the causes of psychosis, Bowie had the right mix of emotional neglect and entitlement to create a man who could face his boyhood demons through creativity. Through Ziggy Stardust and his subsequent personas, he engaged in an internal dialogue played out on an international stage.

There is now strong evidence that childhood maltreatment is the major cause of emotional distress. Maltreatment means such things as emotional abuse (cruelty, favouritism, malice), sexual and physical abuse, and neglect. The best study showed that nine out of 10 maltreated children had a mental illness by the age of 18.

Genes, by contrast, are being proved to play only a minor role. The implications are enormously positive: our psychology is not fixed. Because nurture is so important, we can change the trajectory of our lives, as well as those of our children.

A fundamental means of doing this is personal archaeology – digging into what happened to your parents and grandparents, as well as your own childhood. A simple exercise is to write an account of a day in the life of your mother and of your father when they were aged 11.

It may lead you to understand how that has played out in your life, through the way they raised you: man hands on misery to man, as Philip Larkin famously put it.

For example, one of my clients had a seven-year-old daughter who had appalling tantrums, disrupting the whole family by screa ming, hitting and biting. Using my Love Bombing book, she was able to cure her child. Love Bombing entails the mother removing the child from the family and providing intense, condensed periods of giving the child total control and love, resetting their emotional thermostat.

My client broke a pattern that we traced back four generations. Her maternal ancestors had all reported “impossible” daughters. Yet it was clear the problems had been created by the mothering.

Having traced her “angry mother” persona back to its childhood roots, my client renounced it.

Bowie’s transcendence of the myth of “bad seed” in his family is a model for us all. He showed that we have many different potential selves, more than we often know.

If we can identify them, we can be so much more than the sum of our childhood maltreatment.

Developing a dialogue between the different parts of ourselves, we can resist the cascade of destructive patterns down the generations.

Upping Your Ziggy: How David Bowie Faced His Childhood Demons – and How You Can Face Yours by Oliver James (Karnac Books)

4.5