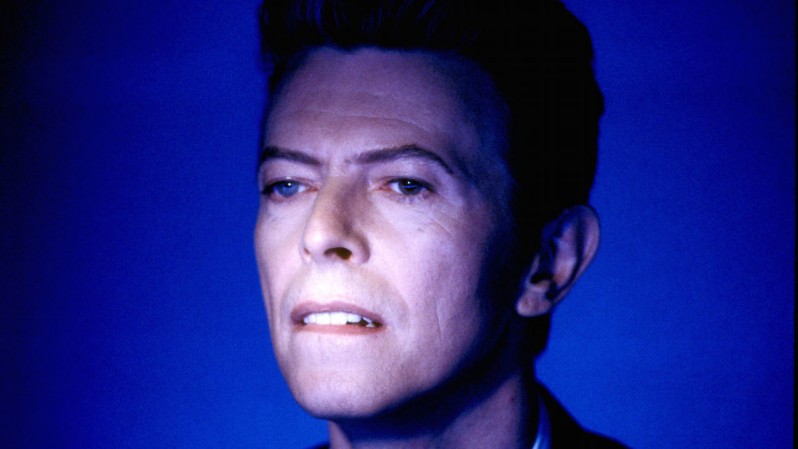

Forget the singles – the 10 greatest David Bowie album tracks show another side to his genius

David Bowie’s sheer plurality makes for one of the most eclectic and distinguished bodies of work in all of rock: glam superstar, soul boy, acoustic folkie, electronic avatar, art-rock pioneer, mainstream pop king. That he departed this world on such a high, with 2016’s stunning Blackstar, has only compounded his reputation. It also means that choosing his finest album-only tracks has become even more challenging…

10) Girl Loves Me (Blackstar, 2016)

Bowie’s death was a massive shock, but longtime devotees could at least take some comfort from the fact that Blackstar was a final artistic hurrah. Full of elliptical clues to his own condition – ‘Where the fuck did Monday go?’ – the otherworldly gait of this song, surrounded by electronic filigree, is both beautiful and satisfyingly strange.

9) Always Crashing In The Same Car (Low, 1977)

A standout from the first album of ‘the Berlin Trilogy’ and a masterclass in restraint, motored by cool synths and Ricky Gardiner’s angsty guitar. Bowie’s measured vocal is in sharp relief to his recollection of a semi-psychotic episode in which he totalled his old Mercedes, supposedly after an altercation with a drug dealer.

8) Queen Bitch (Hunky Dory, 1971)

The black sheep of the mostly acoustic Hunky Dory, Queen Bitch is a feverish rocker (driven by Mick Ronson’s street-fighting guitar riff) that tips its bipperty-bopperty hat to Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground. As Bowie scribbled on the back sleeve tracklisting: “Some V.U., White Light returned with thanks.”

7) It’s No Game (No. 1) (Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps), 1980)

Always one for experimenting, Bowie told guitarist Robert Fripp to “imagine he was playing a guitar duel with B.B. King where he had to out-B.B. B.B. But do it in his own way.” Fripp duly obliged, his fierce aggression matched by the pugnacious vocal interplay between Bowie and Japanese actress Michi Hirota.

6) Aladdin Sane (1913-1938-197?) (Aladdin Sane, 1973)

This underrated gem offsets the impending threat of World War Three with the decadent frivolity of the early ‘70s, Bowie’s paranoia echoed in the dissonant jazz piano of Mike Garson and Trevor Bolder’s ominous bass. Great sax, too. Lyrically, Bowie is typically enigmatic, finding room for a snatch of On Broadway during the outro.

5) Five Years (The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars, 1972)

Woody Woodmansey’s memorable drum intro gives way to one of Bowie’s most urgent expressions of apocalyptic dread. For all its doomy prophesy, Five Years is strangely rhapsodic, carried by a slowly swelling arrangement, oblique lyrics and a vocal line that builds from a plea to an increasingly desperate cry.

4) The Width Of A Circle (The Man Who Sold The World, 1970)

Taken from the heaviest album that Bowie ever made, the opening track of The Man Who Sold The World is an epic showcase for his songwriting ambition and the extraordinary guitar-playing of Mick Ronson. Its sudden shifts and loose tempos place it in prog territory too, Sabbath-ish noise eliding into acoustic passages before re-emerging as convulsive boogie-blues.

3) Win (Young Americans, 1975)

Bowie’s declaration that Young Americans was only ‘Plastic Soul’ was nonsense. His appropriation of black Amercian music was astonishingly well realised, a prime example being this sultry beauty. Bowie’s vocal sounds genuinely anguished, heightened by a dramatic keyboard motif and a harmony trio that includes Luther Vandross. You could imagine Otis Redding singing this.

2) Sweet Thing/Candidate/Sweet Thing (Reprise) (Diamond Dogs, 1974)

In which Bowie offers conclusive proof that, as well as possessing a febrile mind and a singular gift for songwriting, he was also a truly great vocalist. This mini-suite is remarkable, with buzzing sax and spidery piano essaying a post-Orwellian theme of societal decay, eventually sinking into a maelstrom of distorted guitar fuzz.

1) Station To Station (Station To Station, 1976)

A ten-minute monster that finds Bowie in transition from the damaging excesses of his time in Los Angeles to the bold new dawn of life in Europe. Earl Slick excels on guitar, improvising a travelogue saturated in feedback, while Bowie’s tone shifts from the forbidding to the ebullient as the song hurtles towards a rushing climax.