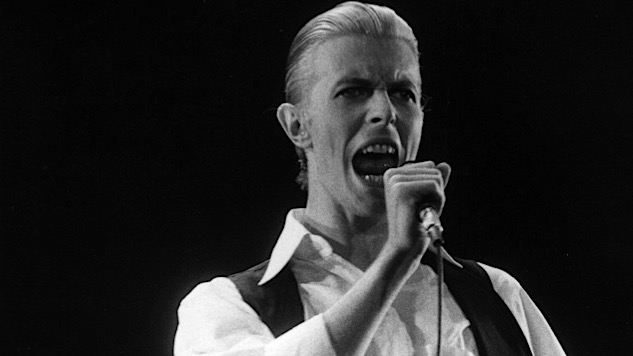

Released 42 years ago this week, the album conjured the Thin White Duke from an Aryan alter-ego, cocaine, a mental breakdown, and a desperate search for meaning.

David Bowie’s grandest masterpiece, Station to Station, was released 42 years ago this week, its creation fueled by “astronomic” cocaine, peppers and milk, an Aryan zombie alter-ego, a mental breakdown with a Hollywood backdrop, the Kabbalah, and finally a desperate search for love and meaning amid profound spiritual confusion.

It’s also a sonic masterpiece on a level unattempted before or since, having been variously described as the merger of “Lou Reed, disco and Dr. John,” “space funk,” “alien dance music” with “a wail and throb that won’t let up,” “a masterpiece of invention” and, according to longtime Bowie collaborator Brian Eno (who was not involved with Station to Station but would produce his imminent Berlin trilogy), “one of the great records of all time.”

The title track kicks off the LP with the sound of a train shoving off—for about 75 seconds, part of an instrumental opening that’s longer than many songs. Then comes the entrance of “The Thin White Duke,” whom Bowie described to Crawdaddy magazine as “The most scary of the lot [of characters he created] because he was the result of all those years of putting characters together. He was an ogre for me. I hadn’t seen England for a few years and when I got back there I found that I’d taken back to England with me a character who was the epitome of everything that it looked like could be happening to England. I saw the National Front and it was obvious to me: There was a Nazi Party in England. Whether or not it was a good thing that I did, I don’t know. I believe the best way to fight an evil force is to caricature it.”

Somehow the opening track that goes on for over 10 minutes (and really is three songs in one) doesn’t seem remotely self-indulgent. Here it is from the Paste Vault on one of Bowie’s most bootlegged concerts from the Station to Station tour, one ultimately included in the album’s reissue.

In fact, the most thrilling thing about the song and the album generally is that it’s so close to completely falling apart, yet not only holds together but soars. After the prog-rock(ish) title track, the album recaptures the white soul of Bowie’s previous record, Young Americans, with “Golden Years” (which Bowie said he offered to Elvis Presley), then rocks in full guitar-hero fury with “Stay.” Here’s a live version of “Stay” from that same 1976 show at the Nassau Coliseum in New York.

Bowie deconstructs and then reconstructs a pop masterpiece in “TVC 15,” and croons with a passion so pronounced it almost seems unreal—and maybe that’s what makes “The Thin White Duke” most frightening—on both “Word on a Wing” and “Wild Is the Wind.” Every track is enthralling.

Though there’s some debate about this, Station to Station was reportedly a failed soundtrack for 1976’s The Man Who Fell To Earth, Bowie’s first big-screen credit. That would make it the second rock masterpiece to hold that distinction, as The Who’s Who’s Next was an abandoned soundtrack for a planned Peter Townshend film (Lifehouse) that seemed to drive Townshend to the edge of insanity, to the point where his bandmates could no longer even follow what he was trying to say.

According to Crawdaddy’s Timothy White writing 40 years ago, “Bowie shuttled from house to house around the Hollywood area, sometimes staying with onetime Deep Purple bassist Glenn Hughes and later moving in with his next (ill-fated) choice for a ‘business adviser,’ Michael Lippman, before leaving for a three-month stay in New Mexico to star in Nic Roeg’s uneven sci-fi film, ‘The Man Who Fell to Earth.’ Reappearing shortly thereafter at Cherokee Studios in Hollywood to record, Bowie was, to quote Lippman, ‘in a very weak mental state.’”

Of the Thin White Duke, Bowie said, “I saw the National Front and it was obvious to me: There was a Nazi Party in England. Whether or not it was a good thing that I did, I don’t know. I believe the best way to fight an evil force is to caricature it.”

Reportage at the time had Bowie seeing ghosts, worrying about witches stealing his semen and living in fear of rock’s reigning master of black magic, Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page. (Movie adaptation, please.) But in the studio, Bowie was grounded by a band that was perhaps the best he ever assembled: Carlos Alomar and Earl Slick on guitars, Roy Bittan of E Street Band fame on piano, plus longtime rhythm section Dennis Davis on drums and George Murray on bass. Slick was key, with Bowie later saying to Kurt Loder as part of the Sound + Vision boxed set, “I got some quite extraordinary things out of Earl Slick. I think it captured his imagination to make noises on guitar, and textures, rather than playing the right notes.”

More recently, Slick said, “It was a very important record artistically because it was the first time somebody took pop songs and twisted the hell out of them but didn’t lose the essence of the song. The only person who was really doing ‘out there’ shit at the time was Zappa, and that was wonderful but it was Zappa. This wasn’t avant-garde, this was pop stuff and nobody had approached a record like that.”

Bowie never went back to either the Thin White Duke or that sound again. No one did. Maybe it was the product of so many destructive forces that he couldn’t revisit. As for the rest, it’s just too perfect and fully realized for anyone else to dare pick up.