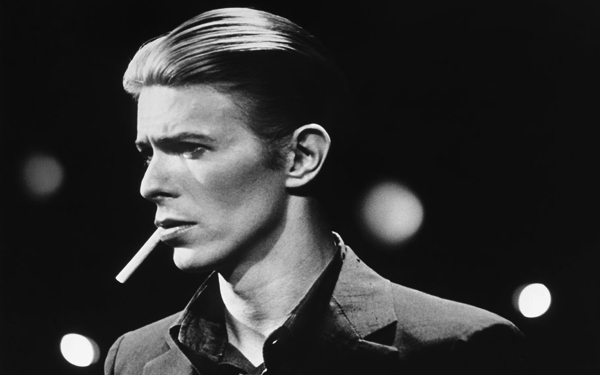

Living an L.A. nightmare, singer-songwriter embraced “nasty” alter ego and made a classic

In 1975, David Bowie moved to Los Angeles, and his life descended into chaos and turmoil. He was consuming massive amounts of cocaine, remaining awake for days on end (“I hate sleep,” he said. “I would much prefer staying up, just working, all the time”), and subsisting primarily on a diet of peppers and milk. At one point, his weight dropped below 100 pounds.

His state of mind was agitated and manic – holing up in a rented house in Bel Air and burning black candles, he claimed to see bodies fall past his window and became obsessed with the occult. In interviews, he proclaimed his admiration for Adolf Hitler (“One of the first rock stars … quite as good as Jagger”) and called for “a right-wing, totally dictatorial tyranny.” The songs on the album he recorded that year, Station to Station, were born from this madness and ended up transcending it as well.

Bowie would later refer to this period as “singularly the darkest days of my life.” Describing the time during a 1999 taping of the VH1 Storytellers series, he claimed it was “so steeped in awfulness that recall is nigh or impossible.” Before performing Station to Station‘s melancholy “Word on a Wing,” he added that the song was “unwittingly … a signal of distress; I’m sure that it was a call for help.”

And yet, according to guitarist Carlos Alomar, when Bowie and the band hit Cherokee Studios to make a new album in the fall of 1975, all of the havoc was left at the door. “When we were in work mode, it was always about the work,” he says. “If it was fueled by coke or by whatever, David was always able to manage the decision-making. And it was always the same concern for him: ‘What are the lyrics, and what am I going to talk about?’

“That professionalism was what enabled him to keep going,” Alomar continued. “He would write something, express something – ‘Get to work, and let’s make the doughnuts.’”

The result was an album that was both musically accessible and lyrically elliptical, a transition between the plastic soul of Young Americans and the chilly electronic hum of the Berlin trilogy that followed – and Bowie’s highest charting record in the U.S. until The Next Day, in 2013. Pioneering critic Lester Bangs, an outspoken Bowie skeptic, wrote that the album “has a wail and throb that won’t let up … a beautiful, swelling, intensely romantic melancholy.” Bowie, Bangs concluded, “has finally produced his (first) masterpiece.”

Bowie went to L.A. for the most American reason of all: to become a movie star. In April 1975, he announced his retirement from rock & roll. “It’s a boring dead end,” he said. “There will be no more rock & roll records or tours from me. The last thing I want to be is some useless fucking rock singer.” (Of course, he had previously proclaimed that he was done with rock during the encore of a 1973 concert in London.)

Under new management after splitting with the unscrupulous Tony Defries, Bowie moved West with a deal to star in and provide the soundtrack to The Man Who Fell to Earth, an existential sci-fi film to be directed by another British expatriate, Nicolas Roeg. Bowie’s lawyer claimed his client had nine finished movie scripts and plans to direct. The relocation was also related to tensions with his wife, Angie.

After testing the waters in L.A. during the spring, he then left the city from June through August for the movie shoot in New Mexico. In addition to his stellar performance as the disaffected alien Thomas Jerome Newton, which Bowie prepared for by studying Buster Keaton, during downtime on the set he was also working on music and on a novel-memoir titled The Return of the Thin White Duke (a copy of part of the handwritten manuscript can be found in the archives at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame).

Roeg had warned Bowie that the experience of playing Newton would be hard to shake, and, sure enough, after the singer returned to L.A., the elegant, emotionally detached Duke – “a nasty character indeed,” said Bowie, complete with a costume of white shirt, black pants and vest – would develop into the last of his great alter egos, in the tradition of Ziggy Stardust and Aladdin Sane. When the book petered out and Roeg rejected the few instrumental tracks that had been recorded for the Man Who Fell to Earth score, Bowie quickly shifted focus back to his usual job and began working on a new album.

Bowie decided to co-produce the album with Harry Maslin, who’d been on hand for his hit John Lennon collaboration “Fame.” Then he called in Alomar, a veteran of the Young Americanssessions. The guitarist was excited to get back in the studio with Bowie but wanted to streamline the way he recorded. After the singer sketched out a song, drummer Dennis Davis, Alomar and bass player George Murray, a.k.a. the DAM Trio, would create a rhythm track. Then the other instrumentalists (in this case, lead guitarist Earl Slick and E Street Band keyboard player Roy Bittan) would add their parts, before Bowie would finally record his vocals.

“With the rhythm section locked down, you had a bird’s-eye view of the whole song,” says Alomar. “We were able to get the skeleton of what we needed, which allowed the other musicians to have a bigger palette of sounds to work with. And the different ways we were looking at arrangements allowed David to look at the music the way he looks at words, which is to cut them up.” It established the way Bowie would record, and the core of his band, for years to come.

As always, Bowie worked feverishly. Musicians got used to being called into the studio at any time of day. “I remember one night when we didn’t even have the studio booked, and I was at the Rainbow Bar and Grill,” recalls Slick. “As we used to say, I was ‘under the weather.’ Suddenly, one of the roadies comes in. They search the whole place and find me at a back table. He says, ‘Time to go to work.’ I say, ‘It’s one in the morning, and I’m drunk.’ He says, ‘That’s OK. David’s at the studio. There’s a car outside.’ So I paid my tab, jumped in the car and worked all night. I mean, that was not an unusual thing to happen.”

Bittan’s entrance into the sessions was equally spontaneous. “I was staying at the Sunset Marquis in Los Angeles when we [the E Street Band] were on the Born to Run tour in 1975,” says Bittan. “I bumped into Earl Slick at the hotel, and he said, ‘I can’t believe you’re here. We were just talking about you.’ When I arrived the next day at the studio, David said to me, ‘Do you know who Professor Longhair is?’ I said, ‘Know him? I saw him play at a little roadhouse in Houston about three weeks ago!’ I wound up doing an imitation of Professor Longhair interpreting a David Bowie song. We began with ‘TVC 15,’ and I wound up playing on every song besides ‘Wild Is the Wind.’ It’s one of my favorite projects I’ve ever worked on.”

The first track they cut was “Golden Years,” the new album’s closest connection to the straight-up soul of Young Americans. Bowie claimed that he wrote the song for Elvis Presley, who turned it down; it would go on to become a Top 10 hit in both the U.S. and the U.K.

Alomar says that the blistering funk-rock workout “Stay” was the real breakthrough. “It was so hard to play that in-troduction, like trying to hold onto a bull,” he says. “Then the song kicks in, and it had that more glass-breaking rock & roll–ness to it. We didn’t want to just go back to making another funk-R&B record.”

A new musical direction was immediately evident on the album’s opener, the 10-minute title track. Starting with the sound of an approaching train, more than three full minutes pass of a slow, hypnotic instrumental march before Bowie’s voice appears. After several stately, cryptic verses, a celebratory groove suddenly erupts, leading into a lengthy, wild outro.

The song also revealed Bowie’s new interest in electronics and industrial rhythms – in “sound as texture,” as he put it at the time. “My favorite group is a German band called Kraftwerk,” he said. “It plays noise music to ‘increase productivity.’”

“Station to Station” also hinted at the drug use, paranoia and odd fixations that were filling Bowie’s mind. “It’s not the side effects of the cocaine,” he sang. “I’m thinking that it must be love.” The title referred not to a train, but to the Stations of the Cross; elsewhere, he drew images from the Kabbalah, occultist Aleister Crowley and European fascist mythology.

“There was so much he was going through – at home, with his wife, the drugs, the pressures,” says Alomar, who remembers spending a lot of time keeping an eye on Bowie’s son, Zowie, during the sessions. “I could feel his pain, but I was there to work, to ground him. He didn’t bring his misery from home into the studio.”

The songs that close each side of Station to Station had a very different tone. “Word on a Wing” was a dramatic hymn that seemed to express Bowie’s confusion about religion. The closing “Wild Is the Wind,” crooned in a torch-song style, was the title track on a 1966 album by the “High Priestess of Soul,” Nina Simone. Bowie had befriended the brilliant, troubled singer in 1974, telling her, “Where you’re coming from, there are very few of us out there.” (“He’s got more sense than any- body I’ve ever known,” said Simone. “David ain’t from here.”)

“At first I thought [those songs] didn’t seem to fit,” says Alomar, “but they took the album into a more human area. They were a release moment so that he could actually cry – there was pain there, and he was able to open up on those songs.”

By November 1975, the album was finished. Bowie hastily arranged a satellite interview with England’s most popular talk-show host, Russell Harty, to announce that his retirement was over, he had a new record, and he would be setting off on a six-month world tour.

Following his three Los Angeles arena shows in February 1976, he packed up the house in Bel Air and moved back to Europe – first to Switzerland, and then to Berlin for the next chapter in his musical evolution.

“I haven’t a clue where I’m gonna be in a year,” said Bowie, after Station to Station was released in January 1976. “A raving nut, a flower child or a dictator, some kind of reverend – I don’t know. That’s what keeps me from getting bored.”

From David Bowie in ‘Labyrinth’ to ‘The Man Who Fell to Earth,’ five decades of star turns and innovative clips from rock’s ultimate video artist.

By

4.5