In England, David Bowie may become—may already be—a real star, but in the American context he looks more like an aesthete using stardom as a metaphor. I’m not entirely happy with this conclusion; it seems almost ungrateful. A week ago, I went to see Bowie’s New York début at Carnegie Hall and ended up standing on my seat; at that, he was subdued by a virus and was much less exciting than when I saw him perform at a British rock club three months ago. Bowie is personally appealing, his act is entertaining theatre, his band rocks, and Mick Ronson, the guitarist, is so sexy he crackles. Yet after both concerts I felt unsatisfied; more than that, I felt just the slightest bit conned. Something was being promised that wasn’t being delivered.

Part of the problem is Bowie’s material. “Hunky Dory,” the first of his albums to get much critical attention, has become one of my favorite records, but his more recent stuff bores me. When “Hunky Dory” came out, I took one look at the album cover—a soft, vague picture of the artist looking soft and vague—and anticipated a soft, vague sensibility. Instead, Bowie turned out to be an intelligent, disciplined, wry Lou Reed freak. To say that his current opus, “The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars” (suggested alternate title: “Jefferson Starship vs. Powerman & Moneygoround”), fulfills the threat of the “Hunky Dory” cover would be unfair, but not very. Some of the songs are O.K.—“Hang On to Yourself,” “Starman,” even “Five Years” when it manages to transcend the self-pity inherent in its theme (the end of the world). But the idea of a pop star from outer space (read pop star as explorer, prophet, poet of technology, exotic on the outside but merely human on the inside, and so on) just doesn’t make it, except maybe as a spoof, and Bowie—or should I say Ziggy?—takes it seriously. “We got five years, my brain hurts a lot. Five years, that’s all we’ve got”? Ouch! Onstage, “Ziggy’s” deficiencies are obscured by Bowie’s flash and Mick’s crackle. Still, Bowie is at his best doing other people’s songs—“Waiting for the Man,” “White Heat White Light,” “I Feel Free.” On the other hand, the worst song in his repertoire isn’t anything from “Ziggy.” It’s “Amsterdam,” by Jacques Brel.

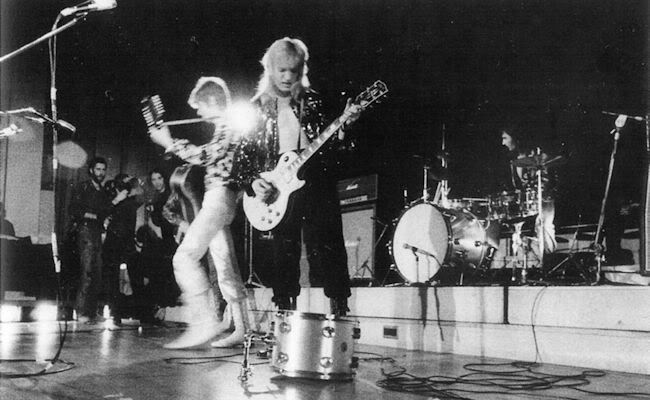

A lot of nonsense has been written about Bowie. The ubiquitous comparisons to Alice Cooper, in particular, can only be put down to willful incomprehension. There is nothing provocative, perverse, or revolting about Bowie. He is all glitter, no grease, and his act is neither overtly nor implicitly violent. As for his self-proclaimed bisexuality, it really isn’t that big a deal. British rock musicians have always been less uptight than Americans about displaying, and even flaunting, their “feminine” side. Androgynousness is an important part of what the Beatles and the Stones represent; once upon a time Mick Jagger’s bisexual mannerisms and innuendos were considered far out. Bowie’s dyed red hair, makeup, legendary dresses, and onstage flirtations with his guitarist just take this tradition one theatrical step further. In any case, Bowie’s aura is not especially sexual; Ronson is the turn-on of the group, and his attractiveness—platinum hair, high heels, and all—is very straight, if refreshingly non-macho. What Bowie offers is not “decadence” (sorry, Middle America) but a highly professional pop surface with a soft core: under that multicolored Day-Glo frogman’s outfit lurks the soul of a folkie who digs Brel, plays an (amplified) acoustic guitar, and sings with a catch in his voice about the downfall of the planet.

I’ve been thinking about all this ever since July, when R.C.A. Records, with unusual promotional zeal, flew a bunch of American journalists to London to see Bowie on his home ground. As it happened, Lou Reed was also in town to see Bowie, who is producing Reed’s second solo album. The night of our arrival, Lou was scheduled to perform at the Kings Cross Cinema, a Proletarian Fillmore that features weekend shows lasting from midnight till six in the morning, and a number of us dedicated fans, undeterred by the fact that we hadn’t slept in some thirty hours, decided to go. The performance could have been better; Reed’s new band not only wasn’t the Velvet Underground but wasn’t even barely competent. Lou wore black eye makeup, black lipstick, and a black velvet suit with rhinestone trimming. (The Reed-Bowie influence, it seems, has gone both ways.) His voice had an unaccustomed deadpan quality, but it still conveyed that distinctive cosmic sadness. It occurred to me that one reason I loved Reed was that he didn’t invite us to share his pain—he simply shared ours. I went to bed at 4 a.m. feeling sombre and drained. The next night, our party was bused to the Bowie concert, which was held at a club called Friars Aylesbury, thirty miles away. Friars was considerably more middle-class than the Kings Cross, and it was mobbed by pink-cheeked teen-agers. They were crazy about Bowie. I was susceptible but confused. Afterward, a group of us went back to the Kings Cross to see some American expatriates—Iggy Pop and the Stooges, one of the original Detroit high-energy bands. Iggy’s thing is hostility; he leaps into the audience and grabs people by the hair. His best song is called “Hungry.” He is also a great rock-and-roll dancer. Unlike David Bowie, he sweats.

On Sunday afternoon, I went for a walk in Hyde Park with Iggy and Dave Marsh, the editor of Creem. We spent a long time trying unsuccessfully to hunt down a vender who would sell Iggy a cold Coke. “This country is weird, man,” said Iggy. “It’s unreal.” Later, Dave and I talked about Bowie: What was it that was missing? “Innocence,” Dave suggested. But maybe it’s just that unlike Lou Reed (who will never be a star here, either) or Iggy (who just might) Bowie doesn’t seem quite real. Real to me, that is—which in rock and roll is the only fantasy that counts. ♦