[et_pb_section admin_label=”section”]

[et_pb_row admin_label=”row”]

[et_pb_column type=”4_4″]

[et_pb_text admin_label=”Text”]

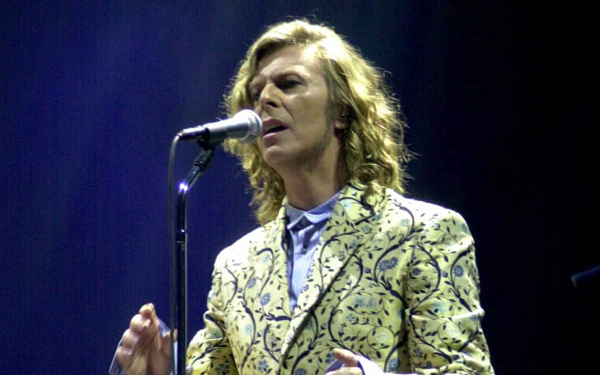

When David Bowie headlined the festival in 2000, the BBC cut him off – and switched to Michael Eavis singing Elvis instead. As the channel finally airs more of the show, the man responsible fesses up

here’s a vast crowd heaving before the Pyramid stage, dusk is turning into night and some shadowy figures have slipped behind their instruments and started to play space-jazz. Here is the culmination of Glastonbury 2000, the millennium festival’s final act, and, for a moment, everything hangs in the balance. Since 1995, David Bowie has released Outside, Earthling and Hours – each sprinkled with the odd cracking song but all grasping rather desperately for the zeitgeist. Bowie’s 53 now, and although he has toured relentlessly throughout the preceding decade, this isn’t his arena or his production. He’s out on a limb and he could fail in front of all these people and the million or more watching on BBC Two …

This was the BBC’s fourth year of filming the festival and I was – as I remain – the overall producer of the coverage. The festival was wilder then, before the wall was built in 2002, and we’d survived two of its wettest years in 1997 and 98. We were determined to make Glastonbury’s headline sets required viewing. We’d had the Chemical Brothers on Friday and Travis on Saturday, but the whole narrative of the festival was built around Bowie. However, there was a problem: Bowie really didn’t want to be filmed.

The first time I’d met Bowie, he’d been performing on Later … with Jools Holland opposite Oasis in 1995. Oasis were in their messy pomp and although Liam had been on a three-day bender, lost his voice in rehearsal and didn’t appear, Oasis still opened the show. Meanwhile, Bowie was notably skittish when he chatted at the piano with Jools, as if in horror of being pinned down. He was back on Later… in December 1999, opening the show with Ashes to Ashes while promoting Hours, but none of these brief encounters helped when it came to Glastonbury 2000.

Weeks of wrangling, cajoling, even pleading through Bowie’s publicist, Alan Edwards, had resulted in an amiable but immovable stalemate. We could film and broadcast the first four songs of the set and then a song or two from the encore, but no more.

We spent an hour’s buildup on BBC Two that night with sets from Embrace and Kelis and a short film in which Billy Bragg brought the then editor of the Spectator, Boris Johnson, to Glastonbury. We had Bowie’s astonishing, hit-laden setlist in our hands by this point and the crowd were chanting “Bowie! Bowie!”

At just after 10pm, Bowie appeared on a backstage camera, looking nervous but determined. Moments later, he was on stage, sporting a three-quarter-length Alexander McQueen frock coat, wonderfully wide Oxford bags and long hair swept to the side a la Veronica Lake. Where had I seen this outfit before? It struck me there and then, that Bowie was referencing his own performance at this very same spot almost 30 years earlier, and that he looked just as groundbreakingly beautiful and “gay” now as he did back then. For all his reputation as one of rock’s great shape-shifters, Bowie had decided to headline Glastonbury as … himself! He launched into Station to Station’s Wild Is the Wind, then China Girl, and already the nerves were gone and he was visibly beginning to enjoy himself. He followed it with Changes, a song he’d debuted at that 1971 Worthy Farm appearance as the sun was rising. We were only three songs in and the crowd were already eating out of Bowie’s hand.

Bowie had not been one for playing greatest-hits sets, but that night it was clear he’d come to reclaim his legend. And as Edwards and I began watching the set in director Janet Fraser-Crook’s scanner, it was obvious we were heading for a broadcasting disaster if we cut it short.

I persuaded Edwards to accompany me to the edge of the Pyramid stage, where he would try and get a word to David via Coco Schwab, his legendary assistant. The set was so clearly going to be a resounding triumph, that surely – surely – this had to be shared with the watching nation? We stood there watching Changes and some of the fourth song, Stay, but there was only a shake of the head from Coco and no sidelong glance from the stage, where Bowie and band were riding high. At least these shenanigans bought our broadcast one more song; assistant producer Alison Howe was charged with staying with the set until I returned to the BBC Two scanner, and so we shared a fifth song – which just happened to be Life on Mars?

I rushed back into the BBC Two scanner moments before the end of Life on Mars? and had to explain to the presenter, Jamie Theakston, that we were coming off Bowie. I should have asked him to explain to the nation that it had been insisted upon by the artist himself. But naively I didn’t want to blame Bowie: it was the early days of our coverage and I hadn’t yet reasoned that the audience’s expectation of a Glastonbury headliner no longer sat with the artist but with the BBC.

Unfortunately we had nothing to screen that might remotely explain why we were coming off the great man in full flow. To the viewers, it seemed as though it was the BBC’s editorial decision. Jamie sat there by the campfire and – clearly smart enough not to take the hit – proceeded to read out the entire setlist. Which we wouldn’t be broadcasting … “I am not sure I’m supposed to do this,” he announced, before running through hit after hit while the sound of Absolute Beginners wafted over from the Pyramid stage.

Jamie promised to bring “an encore or two” from Bowie’s set later on, but that was nearly 90 minutes away. Basement Jaxx weren’t on yet, neither were Ozomatli. And anyway, how could any other band replace Bowie in his pomp? In the end, Jamie introduced a short film exploring the world of underground theatre at Glastonbury, which culminated in Jools accompanying Michael Eavis on some Elvis gospel from the Rabbit Hole. It was bizarre and inexplicable and, if I had been a viewer, unforgivable.

Meanwhile Bowie’s set progressed, constantly scaling new heights. The frock coat came off early but the intensity just kept on growing. At one point he told the crowd: “This is so cool for us, it really is cool – I fucking love it!”

I spent the next two weeks writing to viewers who complained about us not showing more – or all – of Bowie’s set. Since then I’ve often tried to persuade his management to let us screen more of that night’s performance. There were mutterings about audio quality, about some aspects of the performance, but I think the great man already had at least half an eye on posterity.

Of course, Glastonbury 2000 wasn’t Bowie’s last show, far from it. There were the massive Heathen and A Reality tours and then the heart attack on 24 June 2004 in Germany that effectively drove him from the concert stage. Bowie then all but disappeared for a decade, until those final two albums and the brilliantly orchestrated occasion of his passing in January 2016 when, once again, he took centre stage.

info : The Guardian

[/et_pb_text]

[/et_pb_column]

[/et_pb_row]

[/et_pb_section]