A new book from Taschen is out today, celebrating a short but highly memorable period in David Bowie’s career. From his relationship with East End tailors and local hairdressers to Kansai Yamamoto and the creation of Ziggy Stardust, here is a potted history of Bowie’s style from 1972-1973

East End tailoring. A dash of 60s Mod. The first wave of Japanese avant-garde fashion design. Androgynous hair. London’s gay subculture, and even the postgraduate work of Sir Paul Smith’s future menswear maestro. All of these elements were combined by David Bowie into the shifting and striking series of identities he adopted on stage (and in private) during the fleeting existence of his space alien rock star persona, Ziggy Stardust.

Ziggy wasn’t with us for long. There was an 18-month stretch from the Brian Aris photoshoot for the cover of concept album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars, to the dramatic Hammersmith Odeon “retirement” gig in July 1973. But his impact, particularly in the field of personal expression, continues to bewitch and enthrall in the 21st century.

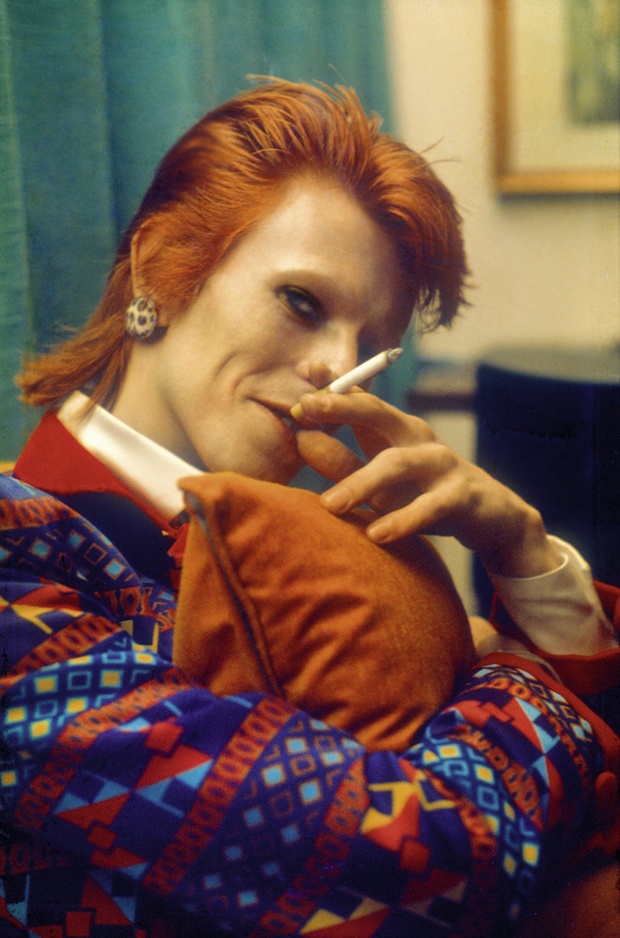

Bowie at Haddon Hall, Beckenham in 1972, from The Rise of David Bowie 1972-1973. Photograph: Mick Rock/Taschen

Bowie at Haddon Hall, Beckenham in 1972, from The Rise of David Bowie 1972-1973. Photograph: Mick Rock/Taschen

It’s arguable that the potency of contemporary British menswear, and, in particular, the prevailing notions of transgression and gender display, owe much to Bowie’s sartorial innovations and experimentations during this crucial period of his career.

From the start – Bowie’s 25th birthday party at his home in Haddon Hall, Beckenham, on 8 January, 1972 – the rock’n’roll chameleon, egged on by his whip-smart and visually acute American wife Angie, was out to dazzle and provoke.

As Bowie archivist Kevin Cann has recorded, on the night of the shebang – attended by the likes of Lou Reed and Lionel Bart – the singer made his entrance down the main staircase in the green Ziggy cover suit of his own design. Gone were the fey garments of The Man Who Sold the World and Hunky Dory eras: no more Mr Fish man-dresses, Dietrich-style locks, Oxford bags, floppy hats or flowing chemises.

Bowie displayed a tough yet ambiguous look of his own design, realised by his tailor friend Freddie Burretti alongside local seamstress Sue Frost. The matching bomber jacket and cuffed straight-legged trousers were produced in the geometric pattern of a 1930s furniture fabric, set off with a fresh haircut (replicating a spiky post-Mod coiffure sported by a model for Kansai Yamamoto spotted in a recent issue of Honey magazine). He accessorised with knee-high, lace-up, zip-sided boots, like those worn by Alex and his droogs in Stanley Kubrick’s film version of Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange.

David Bowie in 1973, from The Rise of David Bowie 1972-1973. Photograph: Mick Rock/Taschen

David Bowie in 1973, from The Rise of David Bowie 1972-1973. Photograph: Mick Rock/Taschen

Bowie built up this aesthetic by drawing on a tight-knit circle of recently formed friendships, particularly those established during his residence in Beckenham: Bowie’s hair was cut by local hairdresser Suzi Fussey (who would dye it flame-red a couple of months later) and the boots – like the quilted suits, also sported by his backing band the Spiders – were bespoke, designed by Stan “Dusty” Miller, who worked for a branch of Russell & Bromley (before it was a nationwide chain).

The party adjourned to Bowie’s favourite London nightspot, The Sombrero, a tiny gay boîte in Kensington where he had met Burretti less than a year before. “Fred of the East End”, as Burretti styled himself, was a prodigiously talented pretty boy. In partnership with his closest friend Daniella Parmar, he wielded a strong influence over Bowie’s style choices, producing the jackets, trousers, shirts, ties and suits in shiny and bright materials which would mint his formal approach to “glam”.

Bowie occasionally selected designs which complemented his and Burretti’s tastes, among them versions of the box-jacketed, wide-trousered suit sold at design entrepreneur Tommy Roberts’ proto-goth Covent Garden boutique City Lights Studio.

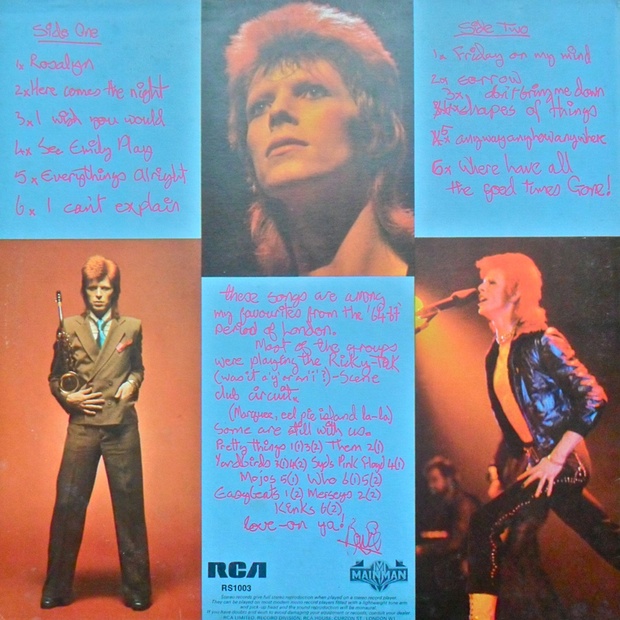

The reverse album sleeve for Pin Ups. Photograph: RCA

The reverse album sleeve for Pin Ups. Photograph: RCA

This was the creation of Derek Morton, who had recently graduated from the Royal College of Art and later became Sir Paul Smith’s head of menswear. Once Mick Rock’s photograph of Bowie in one of Morton’s suits appeared on the back cover of his Pin Ups LP, it proved popular among the soul-boys and proto-punks who would later feed into the New Romantic scene of the 1980s.

“Bowie just wore and wore that suit,” the late Roberts told me in 2011. “We had teams of ‘Bowie Boys’ coming in demanding it ever afterwards.”

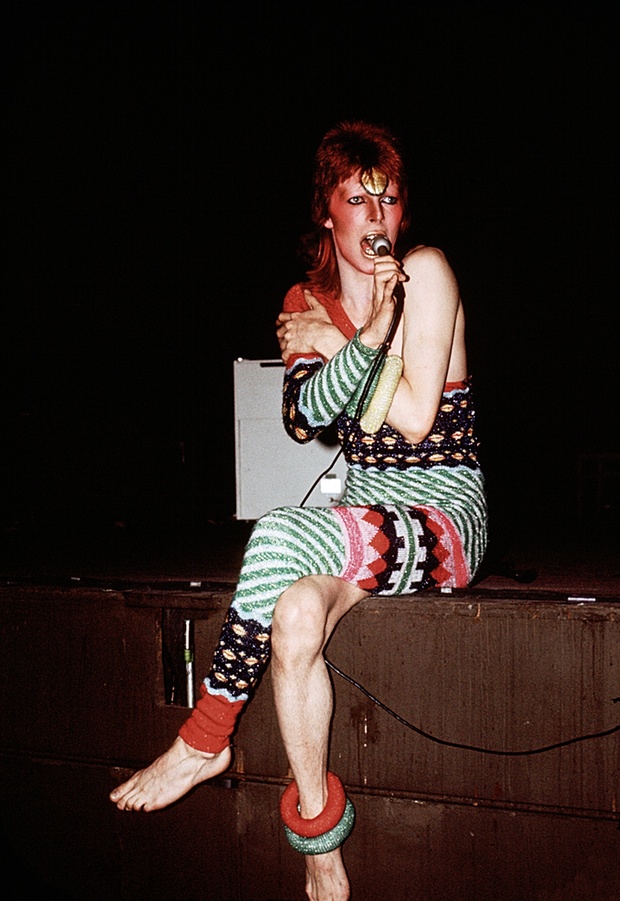

By the time of the Ziggy tour dates at London’s Rainbow Theatre in the late summer of 1972, Bowie was also introducing the extraordinary creations of Kansai Yamamoto as stage-wear. He also followed the Japanese designer’s instructions to his models to shave off their eyebrows (this last effect was combined with the adventurous work of in-house makeup artist Pierre LaRoche).

Bowie on tour in 1973, from The Rise of David Bowie 1972-1973. Photograph: Mick Rock/Taschen

Bowie on tour in 1973, from The Rise of David Bowie 1972-1973. Photograph: Mick Rock/Taschen

Bowie first physically encountered Yamamoto’s work at Boston 151, the Fulham Road shop where he bought the platform-soled red patent leather boots which became one of the integral elements of the second-phase Ziggy look (arguably, as the promotion for his follow-up album Aladdin Sane kicked in).

And just before the world tour of 1973, Yamamoto delivered five newly designed costumes as gifts for Bowie in New York. In the spring of that year, the pair hooked up in Tokyo, where a new raft of designs was prepared for the final leg. This, of course, culminated amid hysterical scenes at Hammersmith Odeon on the night of 3 July when Bowie broke the news that he was retiring Ziggy and the Spiders.

As Bowie uttered the words, “Not only is the last show of the tour but it’s the last show we’ll ever do”, pandemonium broke out among weeping fans. Ziggy was gone, but his flamboyance and willingness to test the outer limits of male visual identity lives on, forever.

Paul Gorman is the author of The Look: Adventures In Rock & Pop Fashion.

4.5

5