By the late ’80s, Bowie was an “adult contemporary” artist. Then, Reeves Gabrels helped him return to form.

This month marks the twentieth anniversary of David Bowie’s Earthlingalbum, a record that saw him experimenting with new forms of electronic dance music. It came in the midst of his creative resurgence, a reaction of sorts to the albums he made in the mid-’80s that seemed to do little more than unsuccessfully chasing the success of 1983’s Let’s Dance.

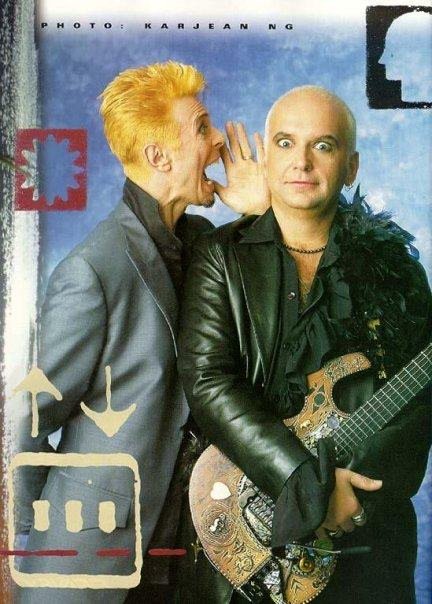

A big part of that resurgence was guitarist Reeves Gabrels, who was a member of Bowie’s late-’80s/early-’90s band, Tin Machine. After that band broke up, he stuck with Bowie, playing on his ’90s solo albums. A trusted collaborator to Bowie, he co-wrote and co-produced much of Bowie’s material during that time, and was also his musical director. And although he left the band in 1999, you could argue that the work he did with Bowie put him on the path to his final album, 2016’s classic Blackstar, which won five GRAMMY Awards earlier this month.

Gabrels hasn’t spoken publically very much about his former bandmate since his passing last year, but he agreed to discuss his entire era with Bowie with Radio.com.

~

You met David Bowie while he was on the infamous “Glass Spider” tour, while he was promoting Never Let Me Down, right?

He didn’t actually know that I was a musician in ’87 when I met him. My then-wife was working for him as his press person during the American leg of the “Glass Spider” tour. I had no business being there, but I had an “all access” pass, and nothing to do. He also often had nothing to do, other than wait for soundcheck or showtime. He and I ended up hanging out in his dressing room until it was time for him to play.

The tour ended in September of ’87, and my then-wife had given him the tape of a band that I was in. I never said anything to him about playing guitar. He thought that I was a painter or a graphic artist. After the tour ended, we moved from Boston to London. After we got there in January of 88, I was walking around London hanging up posters to give guitar lessons. It started raining, and I was soaking wet, but I didn’t bring enough money with me to take the tube back. So I walked through London in the pouring rain. I got home and I started working on some guitar stuff. The phone kept ringing; we didn’t have an answering machine. The third time it rang, I picked it up and was like, [angrily] “Hello?”

“Hi, this is David.”

“David who?”

“You know, David Bowie, we met, you were out on tour with us when your wife was working for me.” I didn’t believe it was him, I thought it was a friend who did a fairly lame David Bowie impression. He said, “I was listening to a tape of yours, and you sound like the guitar player I’ve been looking for.” And I said, “OK, who the f— is this?”

He laughed and said, “Remember, we watched Fantasy Island together in my dressing room in Los Angeles.” And we had done that. We had the volume down and made up our own storyline. So I said, “Man, I’m sorry, I didn’t expect that you’d be calling.”

And he said, “What are you doing this weekend?”

So, I went to his home in Switzerland where he was living. And then we started working on some music together, and we didn’t know what it was going to become. There was no talk of a band. But he told me how unhappy he was with where he had ended up, post-Let’s Dance. Let’s Dance was fun for him, but because that suddenly became his biggest hit ever, the record company wanted him to reproduce it. He said, “I tried to give them what they wanted twice [with 1984’s Tonight and 1987’s Never Let Me Down], but my heart’s just not in it, and it’s killing me.”

And I said, “Well, what does your contract say? Do you have creative control?”

And he said, “Yeah, they have to put out anything I give them.”

I said, “If you’re not happy, you can change it. You just have to have the courage of your conviction. You’re going to have to be able to take being abused by the press if they don’t like that you’re doing something different.” And I remember hearing him say that it seemed simple to me but was complicated to him. And that was a transition point for him.

We also discovered that we were listening to the same contemporary music; we were both listening to old Miles Davis stuff. He was listening to Strauss and I was listening to Stravinsky. I had a Zeppelin bootleg that I listened to a lot, and he had a Cream bootleg that he listened to a lot. We both were listening to Glenn Branca and the Pixies and Charles Mingus and Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane. It just had a kind of “bromance” quality to it.

Related: David Bowie’s ‘Low’: His Masterpiece Turns 40

How did this turn into a band — Tin Machine — as opposed to you being the guitarist on a David Bowie record? How did the Sales brothers get involved? [Hunt Sales played drums and Tony Sales played bass.]

I was actually against the band idea because I had been in bands. The best bands are benevolent dictatorships. My world was quite small at that point, but in my mind, if you were going to be in a band, you were going to be in close quarters with everyone in that band. And then you were basically taking on all of their family issues and personal psychological disorders as your own. So, I didn’t really want to be in a band with the Sales brothers!

Originally we were going to work with Terry Bozzio [the former drummer of Missing Persons, who had also played with Frank Zappa] and Percy Jones [the bassist from jazz fusion band Brand X] as the rhythm section. And then he called me up and left me a message, and said, “I was just in L.A. and I ran into our rhythm section.” And then when I met the Sales brothers, they were crazy and wild. I was in art-rock bands, and I was more intellectual and brooding. I was that cliche. And they, in their youth, were the “destroy-the-hotel-room” types. And I thought, “This is all well and good,” but I guess I really wanted to be the guitar player on a David Bowie album, not in a band with him.

What was the chemistry like?

The chemistry was there: David, Hunt, and Tony had played together, behind Iggy Pop [editor’s note: you can hear them on Iggy Pop’s live album, TV Eye ’77]. So they already had this vibe. Whereas I had just met David, and he was kind of treating me — I hate to use the word “mentor” — but he was taking a very brotherly attitude.

My experience at the time was basically indie bands in Boston. I’d played the northeastern country circuit and the northeastern chitlin circuit. In 1985, I played a hundred and seventy something weddings. I had done the Malcolm Gladwell “outliers” thing: you know, the theory that you had to spend 10,000 hours on something to do it well.

I guess David recognized something in me, and we got along really well. The first month that we were working together, we watched all of these obscure Monty Python things that he had collected and [BBC sitcom] Fawlty Towers, and I went through his wine cellar. It was just he and I at his house, and we had a great time. But then the Sales brothers came in and I immediately noticed this sort of “band-ish” chemistry between them. The Sales brothers had a telepathic way of playing together.

So David comes in one day and says, you know, I was thinking, “This should be a band. You guys don’t listen to me anyway, you just do what you want to do, so why don’t we make it a band?”

I was like, “Well, I don’t know: these guys seem a little crazy.”

So it became a band, as opposed to being David Bowie’s backing band.

There was a moment where I was doing an overdub in the studio. The studio we were using had no visual sightline to the control room. So every time I’d play something, they’d say over the speaker, “Play it more like Albert King!” “OK.” Then: “Play it more like Jimi Hendrix!” “Play it more like Jeff Beck!” “No, play it more like Leslie West [of Mountain]!”

Finally, I said, “Look: I appreciate the input but I know what I want to do here. So just shut the f— up!”

And the next time I heard them on the talkback mic, they were all laughing hysterically. And that was the day: “Today, I am a man.” That was the day that they realized, I guess, that the chemistry was going to work. They realized that they could push me to the limit and I could give that s— right back to them. And for me, that’s when it became a band.

It was surprising to the public for him to be in a band.

David had a rejection letter for Low from RCA on his wall and they suggested that he go back to Philadelphia and do something more like Young Americans. He said, “They might hate this [band] now, but in twenty years they’re going to love it!”

We were grunge before it became a thing. Nirvana asked [Tin Machine producer] Tim Palmer to make the record that became Nevermind, and Tim mixed Pearl Jam’s Ten. He said that one day he walked into the studio and they were playing [Tin Machine’s] “Heaven’s In Here.”

It seemed very in-your-face, compared to what Bowie had been doing for the past few years.

I didn’t think we were particularly abrasive… I was listening to Ministry and Pigface and Suicide and a band called the Blackouts, so I knew what hardcore s— sounded like.

I think [the band’s 1989 debut] Tin Machine stands the test of time, and what I’m pleased by is that a lot of people have gone back and looked at it again. In looking at it again they realize, “Hey, this is a good album, and these are good songs, what was everybody mad at?”

By the mid-’80s, it seemed as though Bowie was in the same league with guys like Elton John, but Tin Machine was more like Jane’s Addiction or Living Colour or Faith No More.

I said to my ex-wife while I was watching the “Glass Spider” tour, “Boy, I would love to do something with David and make him rock again, in a contemporary way.” And the next thing I knew, I was in a band with him.

In 1990, Bowie went on his “Sound + Vision” tour, promoting the reissues of his catalog, playing his hits in huge venues. Knowing his history of not staying with collaborators for very long, were you worried that Tin Machine was over?

No. We had done the Tin Machine record. He told me before the first record was half done, “I’m contractually obliged to do this tour in 1990.” A couple of months later, we were mixing the album, and he asked me to play guitar on the tour, and be the bandleader. I said, “If we’re really working on making it clear that Tin Machine is a band, that doesn’t seem like a smart move for me, or for us.”

What was funny was I had a band in Boston called Life On Earth. We used to get called whenever Adrian Belew came through town with the Bears or his solo tours, we’d get the call to be the opener. So I knew him, we used to hang out. There was a show where we didn’t open, but they invited us down, just to hang out.

So I said to David, I didn’t want to play those other [guitar players’] parts. But I said, “What about Adrian, he played with you before?” He was on [1979’s] Lodger and [the 1978 live album] Stage.

He said, “Do you have his number?” So I called up Adrian, and I said, “I have this friend who is going on tour, and he needs a guitar player. He asked me and I can’t do it, but I thought you might want to do it,” and I put David on the phone.

What a strange sense of focus I had at age twenty-nine that I said “No” to playing on a David Bowie tour.

The Tin Machine record came out in May of 1989, and by August of 1989, we were done playing live shows and we went to Australia to make the second record. And then I continued working on the tracks with Hunt and Tony, and I would chase David around the country with the master tapes.

But I wasn’t worried about David leaving; people on the tour later told me that they were always saying, “I’m so tired of hearing him talking about this Reeves guy and how he can’t wait to get back with Tin Machine!”

The thing about David was, he would get the hots for the new thing. And then once the mission was accomplished, once the experiment ran its course, he’d move on to the next thing. He said it himself: he was like a casting director: he’d get an idea in his head, and then he would cast the people. Through my tenure, he was always the same guy. It was the people around him that changed, and that changes the music.

Didn’t he say that his solo career was over, and he’d just do Tin Machine from then on? Did you believe that?

The thought was that once we did the first record that we would be like Neil Young and Crazy Horse, and we’d all have other things [but continue to record together].

When Tin Machine II came out, fans were surprised that the first single, “One Shot,” was produced by Hugh Padgham. He’d produced Bowie’s Tonight, not to mention Genesis, Phil Collins, the Police and Sting. That seemed like a very non-Tin Machine move.

We recorded that song the way we recorded everything, with Tim Palmer producing. Victory Music’s owner Phil Carson begged us to re-record it with Hugh Padgham [the band was signed to Victory Music at the time]. The thought was that radio would play the song if they saw Hugh’s name. And he’s a lovely man and a talented man. I just listened to the original version the other day, the only difference is the hi-hat pattern. And I think the guitar solo is better on the Hugh version. But they’re almost identical. I hope at some point we put it out; we could put out a four or five CD box set because there’s an album of material that never got released, plus there’s alternate material, and live stuff. Tin Machine could have been a double album, and [Tin Machine’s 1992 live album] Oy Vey Baby could have been a double album.

After that, he did a solo album, 1993’s Black Tie White Noise. You guested on “You’ve Been Around” from that album, but at that point did you think that Tin Machine was over?

He and I talked about it, so I knew what was going on before he started Black Tie White Noise. “White Noise” was what I originally wanted to call Tin Machine, but David thought it sounded too racist. But then he married Iman.

The song “You’ve Been Around” was actually recorded for Tin Machine, and he redid it [for this album]. I played on two more tracks, [the cover of Cream’s] “I Feel Free” and one other one, but I wasn’t credited. I did the original solo on “I Feel Free,” but David called me and said, “Would you mind if I had Mick [Ronson, formerly of Bowie’s Spiders From Mars band] play on this?” I was like, “Sure – I played rhythm guitar on that too, so at least I’ll be on the same track with him!” But all the other stuff I played on the other tracks got claimed by Nile [Rodgers, the album’s producer]. David said, “When I reissue it, I’ll correct that.” But I don’t know if that happened.

Meanwhile, Phil Carson from Victory also managed and signed Paul Rodgers. I remember playing along with [Rodgers’ former band] Free’s records in my bedroom as a kid. He asked me to go on the road with Paul while David was promoting Black Tie White Noise.

I remember being in Oklahoma City on the Paul Rodgers tour, and David, Brian Eno and I were faxing each other ideas. One night I came off stage, the audience is still singing [Free’s] “All Right Now,” and I thought “What a weird life this is!” I get off stage and I have a fax for me from David Bowie and Brian Eno.

By 1994, it was time to go back to working with David. I had the keys to his houses, I had his ATM card and his code. He didn’t like to go to the cash machine by himself on the way to the studio. He’d just call me up and say, “Can you grab me some money on the way to the studio?” Our connection and our friendship was beyond “I don’t know if you’re going to be in my band this time.”

But you went from being bandmates to you playing guitar on his solo album. And Brian Eno was there.

It was a little odd because I got to the studio a week before Brian. The things on [1995’s] Outside that are just written by David and I were written before Brian and the rest of the band came in. The things with six writing credits were pure improvisation. Like “The Heart’s Filthy Lesson” and the interlude pieces. For two months, we’d play five days a week and record stuff and improvise for two hours a day.

David and Brian were producing, but when I’d come downstairs, David would ask me “Reeves, what do you think?” And it was really a question that should have been addressed to Brian. Brian and I got along great. But I used to get embarrassed by that.

But Brian and I had dinner almost every night. He educated me… he has a very educated palette about wine. He argued that wine is the most highly evolved drug and he proved the point on a nightly basis.

When you guys toured for that album, you co-headlined arenas with Nine Inch Nails, who had headlined some of those same venues on their own about a year earlier. How was that tour?

Trent and I hit it off. I glued a chair to the stage in front of his microphone when we were doing production rehearsals. Just as a joke. And Crazy-Glued guitar picks with my name on them inside his guitar cases.

There was one song where I used to play my guitar solo with a vibrator. I lost all sense of it being a sex toy. So I used to keep one hanging from my mic stand. And one of our first shows, there was a condom on it. We had these practical jokes going back and forth.

They were a pretty wild bunch, and we played a few songs together every night. I was always pretty stable in a sea of insanity, and Trent used to seek me out when things got too weird. He felt like they went back on the road too soon after their last tour, but he didn’t want to pass up the opportunity to tour with David. And David — and I was right behind him — wanted the challenge of going on stage right after Nine Inch Nails. We had to frontload our set with the harder stuff, like “Hallo Spaceboy.” Plus, we didn’t play many of the hits.

Trent wanted the fans to see what influenced him, and David wanted the fans to see how vital his music still was.

If you look at my time with him, our shows were kind of light on the hits. With Tin Machine, we didn’t play any of his solo songs. With the Outside and Earthling tours, we played some, but he let me rearrange them. On those tours, we did some odd things like [Laurie Anderson’s] “O Superman” because Gail [Ann Dorsey, bassist] could carry the Laurie Anderson vocal and we did “Under Pressure” because she could carry the Freddie Mercury vocal. “Under Pressure” would get people excited, and so did our version of “The Man Who Sold the World.”

It was a risky tour. When I saw it, it was about three days after Outside came out. Obviously, you couldn’t really stream or download music back then; if you didn’t have the chance to go to the record store, you would not have heard any of the new songs, and he played a lot of them.

Being David’s musical director and his friend, I was all about taking chances. That’s to me, what rock music is about. I think some of the folks in the business office… I was not their favorite person. We didn’t lose money, but we didn’t make as much money as they wanted us to. We did uncompromising stuff. I grew up thinking of David as someone who did what he wanted and didn’t chase the tail of something else.

In August of ’96, the tour ended, and we were going to take a couple of months off, but we ended up only taking two weeks off. I was writing stuff on my computer, and some of those songs became the songs from the Earthling album. But around that time we also did his 50th birthday show. My job was to sit down with all the guests and make sure they knew the songs. That was when I met Robert Smith [of the Cure, the band Gabrels now plays in].

We went out for all of 1997 for the Earthling tour, and that was the best tour I ever did with him. Zack [Alford, drums], Mike [Garson, piano] Gail [Ann Dorsey, bass] – we feared no band at that point.

ou and David co-produced Earthling.

Mark Plati co-produced that with us. Most of the time it was David and I and Mark who was hired to engineer. We wrote everything in the first two weeks. Mark and I had a good working relationship and David trusted us. I think I co-wrote seven songs. I argued for a shorter album, for a change. That music was going to be a bit of a challenge for people. I kept some songs off the album, and David trusted my judgment. That was my favorite period with David. I was into Prodigy and Fluke and a bunch of different electronic bands. Most of them didn’t have guitar, but I was determined to find a way to make guitars work. The one thing about doing stuff with David was that… he was David. If he did something that was challenging, it became the thing that everyone was going to copy in the next five years.

It felt to us that this was the second golden age for David. We felt like we had the kids on computers, the Nine Inch Nails fans, the girls who went on to become Abby from NCIS.

After that, you did [1999’s] Hours.

At that point, at that point, David said, “Let’s not worry about who writes what and we’ll just credit everything to both of us, like Jagger/Richards,” which was very generous of him. But the irony was, I wanted to do Earthling 2.0, because as we toured for that album, I thought of all the things we could have done differently and all the ways we could have made it better. But it was a case of him feeling like he’d done that. “Now I want to do something that’s more songwriter-ly.” Songs like “Seven,” you could sit around the campfire and play on acoustic guitar.

“Thursday’s Child” is one of my favorite Bowie songs.

It’s a funny song. I feel like the album didn’t really get the attention it deserved… an additional reason for my departure was, we were going to tour, and I sat down with David’s business manager and David’s assistant at the time who, it became clear, wielded a lot of power. She didn’t want to go on the road. David had toured a lot in the ’90s, and everybody but me wanted to stay home.

With a legacy like his, it’s a little bit like a kingdom. There’s the power behind the throne, there’s the jester. The rest of the band used to call me the “Teflon Prince,” because I could f— up and get away with it.

Is it true that he wanted TLC to sing backing vocals on “Thursday’s Child?”

That’s completely true. We got Holly Palmer, who was a friend of mine, an amazing singer that I knew from Boston. She had gone to Berklee like I had, and she was one of those singers whose voice was an instrument. You could give her sheet music and she would sing it.

When he told me he wanted TLC, I was like, “TLC? I stopped listening to you when you sang with Bing Crosby! I was so pissed off I didn’t buy your next two albums! Now we’ve acquired the audience that we wanted, and you’re gonna put TLC on the record, and they’re going to say, ‘F— him!’ And I know better singers than that!”

So I called Holly and put her on speakerphone, and David asked her to sing [TLC’s] “Waterfalls.” And she did and then he said, “OK, now do it without vibrato.” And she did. And then he said, “OK, now do it with more vibrato.” And she did. And he says, “Can you come to the studio right now?” And she did, and she ended up singing on “Thursday’s Child,” and was in what became the next touring band.

But “cool” — in quotes — is a very subjective thing. I was David’s friend, and his guitar player, musical director, co-producer, but I was also a fan. I felt like I was protecting his “thing.” I wanted to make sure he stayed cool and stayed connected. He was a voracious chaser of new things. But not every new thing [should be chased].

We did a different version of the Hours record, and I had played bass on that, and we let it sit and then we listened to it, and David said it was too raw. I thought it had a certain Diamond Dogs quality, but he wanted it to be more slick and polished and have fretless bass.

There’s a track from the Hours era that was a b-side called “And We Shall Go To Town” that I thought was a key track for that album and it ended up being taken off the album, and that was part of the final straw for me. It was a very dark track. Because every song was co-written, it wasn’t like I was trying to get a song on the record because I wrote it. I felt like the mood on the record shifted. The song was about two people who were so grotesque, horribly disfigured, and people would stone them on the street, and they grew tired of having to live in the shadows, it’s like an “Elephant Man” thing. And they think “Tonight’s the night we go to town. This might be our last night on earth because people will probably kill us.” That was a little less jolly than “Thursday’s Child.”

His circle of friends was more in his age group and they were listening to Luther Vandross and things like that… and I wasn’t. He actually made a comment to me at one point, “I want to make music for my generation.” And I said, “You always just made music that you wanted to make, and if you want to make music for your generation, you’re ten years older than me. So where does that leave me in this equation? I don’t know how to produce that. I don’t know how to help you if that is the new criteria.” The whole thing started to feel claustrophobic to me.

I knew from January of ’99 that there was a long road for me to leave him, without leaving him hanging.

And it became apparent that there was not going to be a tour, it was just a promotional tour of Europe where the performances were all lip-synched. Mark Plati came in at the end of Hours to play fretless bass and remix the record. I knew that David was comfortable with him and he was an excellent musician and arranger and a killer bass player and he can play guitar and keyboards too, and David trusted him. I kind of groomed Mark to take my place as musical director. And that’s basically what happened.

The last show that I did with him, VH1 Storytellers [recorded in 1999, released in 2009], that was when I was trying to stage my departure, I asked Mark Plati to come in and play acoustic guitar, I wanted David to get used to him. I put Mark next to David where I used to stand. I cannot remember whether that was conscious or unconscious.

I had played stuff on a single for the Cure [“Wrong Number”], I had done some stuff with Nine Inch Nails, all because of my connection with David. I will forever be in his debt. But I was running out of ideas for him. I was afraid that if I stayed, I would become a bitter kind of person. I’m sure you’ve spoken to people who have done one thing for too long, and they start to lose respect for the people they work for, and I didn’t want to be that guy. The most logical thing for me to do at that point was to leave and do something else.

Did you listen to Blackstar or any of the other music that he did after you left?

Well, I’ve got to say the only track I’ve listened to, other than “Blackstar” is “Everyone Says ‘Hi’” [from 2002’s Heathen] because someone told me that David wrote that for me. That made me cry.

Actually, I thought that [2013’s] The Next Day sounded like outtakes from Hours. I say that only having heard two tracks from that so I am contradicting myself somewhat. On “Blackstar,” he sounds like a man who is writing and singing music like his life depended on it. I can see a more direct line between Outside and Blackstar…. if we would have had computer technology like when we did Outside – we cut tape with a razor back then – but conceptionally and compositionally Blackstar resembles Outside in a lot of ways.

I can’t explain how saddened I am by his passing. But – he really pulled it off, he turned his whole career into art by doing that record as his final statement. To me, it’s the real capper to a blazing career.

What was your relationship like after you left the band? Were you in touch with him?

I departed under good terms, but then it got weird, and then we resolved all that around the time of his bypass surgery. The friendship didn’t become as conversational as I would have liked, but I think it has more to do with the people around him than it does with him. But on the other hand, just because you weren’t talking to him, it doesn’t mean he wasn’t thinking about to you.

One of the funny things he used to tease me about was, “When I die, you’re going to make a ton of money,” because we wrote, like, forty-eight songs together. I wish we could have an afterlife conversation about that one just so he could gloat. “See! I was right!”

I remember when I found out about 2:30 in the morning on a Sunday that he’d passed, I was laying in bed, my partner woke me up; she’d heard from Duncan [Bowie’s son]. I just kind of laid in bed and I started laughing. She said, “Why are you laughing?” I said, “Because we had so much fun.”

I thought about being in the studio with him and cutting a hole in a water cooler jug, and spending an hour with him putting his head in it, and we dropped a mic in through the spout and recording vocals. Stuff like that. Just the silly things that we used to do.

That stretch of time, I’m proud of it because we didn’t do anything we didn’t want to do. I think the biggest compromise was doing “One Shot” with Hugh Paghdam.

Well done, my friend. The world has the music. What I remember most is the laughing. @DavidBowieReal

I haven’t really spoken much to people about him [since his passing]. I’ve avoided all the tributes. The irony of the tributes is that David didn’t really enjoy playing his hits. So the idea of putting a band of Bowie alumni to back singers who wish they were David upsets my stomach, so I’ve stayed away from that stuff.

I put out what amounted to a press release saying that I was deeply saddened to hear the news, but I just remembered all the fun we had and also how David surrounded himself with the best musicians and brought out the best in them. Now’s the time to go deeper in the catalog. Now’s the time to play b-sides — to paraphrase [Blue Oyster Cult’s] “Burnin’ for You” — and not turn him into a t-shirt that millennials wear so that they look hip. I see that happening already. Don’t turn him into Elvis Presley. Don’t put his face on a coffee mug. That’s not what it’s about.

The whole idea was to not chase what was happening but to define what could be happening. The goal was not to be what already is but to show what possibly could be.

4.5

5