At 8am on 11 January this year, Paul Morley’s mobile phone rang next to his bed. He had set a late alarm because he’d been up until 5am writing a BBC radio script about visiting art galleries, which mentioned David Bowie and which had been written to an early-hours soundtrack of Bowie songs. On his voicemail he heard a young man briefly apologising in case he had not heard the news that Bowie had died: could he comment on the Today programme that morning?

Once he had absorbed the initial shock of finding out that the singer’s “cheering, on-going life” had ended two days after his 69th birthday and the release of his 27th album, Blackstar, Morley decided to avoid answering his phone for the rest of the day. It then became clear to him that “the only way I could begin to say what I wanted to say about David Bowie was to write a book”.

Anyone could have written a book solely comprising the memories, tributes, odes, affectionate jokes and straightforward obituaries of Bowie that emerged in a rush during that raw January week. Morley says that, instead, he chose to write the only sort of book that he could have written about Bowie: part love letter, part biography, part autobiography, part theoretical framework for life.

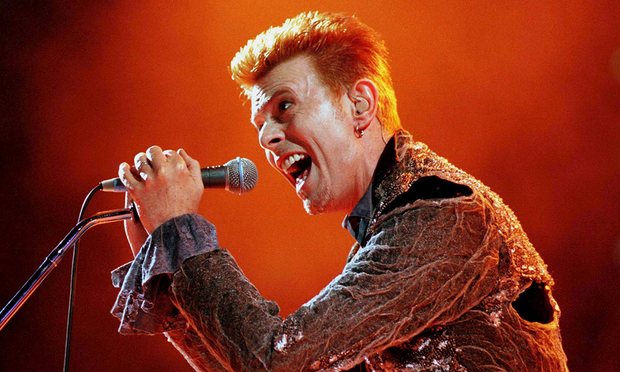

For Morley, it appears that “everyone has their own Bowie” – “even Bowie himself was only a contributor” to the idea and the ideal that Bowie became. The notion that there are lots of Bowies, and that he is a sort of human compass, pointing the way for misfits adrift and repressed in a world of conformity, comes most obviously from the fact that he changed his sound and his appearance repeatedly throughout the 1960s and 70s without diminishing the qualities that made him so magnetic to his fans.

But he is not just Aladdin Sane, or the Thin White Duke, or Labyrinth’s Jareth: he is an “infinitely interpretable” cipher, “a hypersensitive light entertainer who was amazingly also a socio‑historical antenna, for some not their cold, bitter cup of tea at all, and for some a glorious almost saintly way of defining their difficult, lonely outsider-ness”. Bowie infused pop music – cheap music, as Noël Coward called it – with art’s endless possibilities; his first love was jazz and he spent his life reading books as though he needed them more than food.

Morley gets to the heart of Bowie’s appeal by wearing his heart on his sleeve

Morley finds Bowie’s socio-historical antenna significant – he was both a product of his time and someone who made an artistic career out of anticipating what was to come next. Born out of wedlock in 1947 into “an anonymous working family”, David Jones came from Brixton, moved to suburban Kent in the early 1950s, passed the 11‑plus but chose to go to technical school instead of grammar school, and spent his teens making the best of two extraordinary strokes of luck.

The first was that his most inspiring teacher, Owen Frampton, was also his art teacher, who encouraged the idea that “education could be about joy, and change”, and got his students to think about design and advertising as facets of art. In effect, Bowie took this to mean that you could combine all three at once, using his own body as the design; his teasing, opaque interview persona as the advertising; and pop music as a mutable vessel for serious art.

Second, having decided at school that he wanted to become a jazz saxophonist (on hearing this, the careers officer at Bromley Tech advised him to get an apprenticeship in a local harp‑making factory), he looked up teachers in the phone book and found that Ronnie Ross – sometime player with the Modern Jazz Quartet – lived around the corner in Orpington. Bowie’s jazz training defined the incomparable precision-cum-imprecision of his music, which approximated an infinite number of existing styles and melodies, yet came out sounding like nothing, and no one, else.

Morley, an obsessive Bowie fan since first hearing him on John Peel’s Radio 1 show in 1970, gets to the heart of the singer’s appeal by wearing his heart on his sleeve. For someone who loves not just pop music but everything – the artifice, social significance, glamour and dress codes – that goes with it, Bowie remains an obvious exemplar of its possibilities.

The art critic Dan Fox’s recent book, Pretentiousness, defends the bravery of pretension, and the idea of overreaching, in culture: it makes the rest of us a bit more brave, or at least open to the idea that it’s better to try hard and look silly than not to try at all. This is exactly what Bowie did for millions of people, including Morley, a music critic whose writing – going back to his days as the NME’s resident cultural theorist in the late 1970s and 80s – has attracted regular sneers of the Pseud’s Corner variety, for daring to read depth into something that appears shallow.

When asked to advise the curators of the Victoria and Albert Museum’s huge exhibition of Bowie artefacts in 2013, Morley’s contribution was the “conceptual kit/concrete poem/manifesto”, David Bowie Is …, which became the show’s title. Throughout this book, he lists the many various ways in which Bowie is, including the psychoanalytical “Bowie is where we start from”.

“Bowie is always changing,” my four-year-old son tells me when we play his records. I start to say, “Well, he was always changing”, and then realise that’s not the point. Bowie is new to my son and therefore still alive. This is precisely Morley’s thesis, which he examines over 496 pages of clearly rushed, sometimes repetitive, but engaging writing. Bowie will stay alive, and will continue to keep changing, for as long as we are able to listen to his music – and for as long as we can look at pictures of him, reminisce and think about him.

Morley ends his moving paean by imagining Bowie, close to the end of his life, crouching in a cupboard as he films the video for his final single, Lazarus, in which – it became clear – he told us he was dying. In Morley’s vision, Bowie sits in the dark, thinking about the life he has had, wondering if it can possibly get any darker in there, when “a voice says I just wanted to say thank you. Thank you for everything.”

5