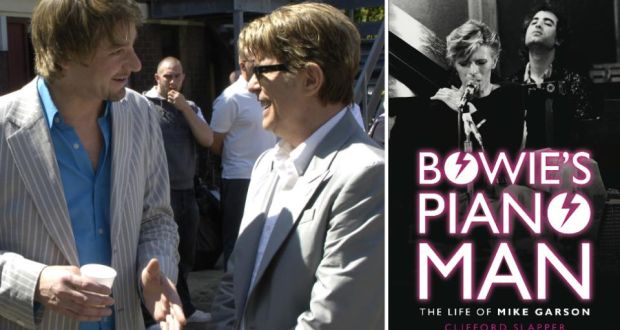

Clifford Slapper at the party with Bob Slayer yesterday (19 march 2015)

Yesterday, I went to writer Polly Trope’s birthday party in Soho. Last April, I blogged about her ‘autobio-novel’ Cured Meat: Memoirs of a Psychiatric Runaway.

Musician Clifford Slapper was also at her party yesterday. He, too, has written a book, published today. It is a biography – Bowie’s Piano Man: The Life of Mike Garson.

“Have you ever worked with Bowie?” I asked.

“On Ricky Gervais’ comedy series Extras,” replied Clifford. “David Bowie had a cameo in one episode. I was David Bowie’s hands for the day – playing the piano you hear on the show. There was another piano hidden off camera which I was playing and Bowie had to sing and pretend to play. That was very exciting, because I’d been such a fan of Bowie’s for years and we had to spend a day of rehearsals together, just the two of us, and then the following day filming. He was very unassuming, really easy to work with.

Clifford Slapper (left) chats with David Bowie (Photograph by Ray Burmiston)

“A couple of years later, I met Mike Garson in Los Angeles. We were speaking about David Bowie and how he loves English comedy and Mike said: A couple of years ago, there was this really funny British comedy and David was playing the piano. I spoke to him and slightly teased him and said Your playing’s come on quite well – because Mike knew David played the piano but not like that.

“David had immediately laughed and told Mike: No, no no. That was some guy from England. And I was able to sit there quietly, then tell Mike: I was that guy. He and I partly bonded over that and we were swapping stories about the ups and downs of being a musician. And I said to him: Look, there are dozens of biographies of Bowie. Has anyone ever written your life story? That was five years ago and now the book’s out.”

“Why,” I asked, “did you, a musician, think you could write a biography?”

“I have written a lot of political feature articles,” Clifford told me, “for a Socialist magazine, the Socialist Standard.”

“Why a book about Mike Garson?” I asked.

“In the late 1960s,” Clifford told me, “he was a New York avant-garde jazz musician playing tiny gigs in smoky basements. He was married with a baby and struggling to make ends meet. He came home to his wife one night in the autumn of 1972 with $5 – that was his pay – and said: I can’t go on. I can’t feed three of us.

David Bowie in 1967, still an unknown performer

“The next day, he got three surprise calls, all offering him larger music jobs. Two were for Big Band jazz stuff, going on the road. The third one was from Tony Defries, David Bowie’s manager. The album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and The Spiders From Mars was out, Bowie had been touring Britain as Ziggy Stardust and captured people’s imagination but was not particularly known in the US: they were about to do their first US tour.

“Tony Defries told Mike: David Bowie wants to add an avant-garde ingredient to his music and you’ve been recommended. Would you come on tour with us around America? And Mike’s reply was: David Who?

“But, a week or two later, there he was on the road playing rock concerts to thousands of people. He was catapulted from dozens to thousands. He was in his late twenties, but was actually the old man of the band because the rest of the band were in their early twenties.

Mike Garson, 2006 (Photo by Alex Boyd)

“He toured the world with Bowie 1972-1974 and was featured on several of the key albums of that period. Then there was a very long hiatus until the late 1980s and then he got the call again at the outset of the 1990s and again recorded and toured with Bowie right into the 2000s. Last time they played together was 2006.”

“I’m not a musician,” I told Clifford, “why should I be interested?”

“Human interest,” replied Clifford. “And because we’ve approached his life thematically. It’s not a dry, chronological account. We examine the themes that emerge from his life. We have a chapter on addiction – of all kinds. Not because Mike has suffered from addiction but, ironically, because he has not. Almost everyone else in those circles has.”

“So he can give an objective view?” I said.

“Exactly,” laughed Clifford. “He’s one of the few people who did the big rock tours of the 1970s who can remember anything about them.”

“Musicians, actors, comedians,” I said. “Performers in general seem to have addictive personalities.”

“I think,” said Clifford, “that it’s to do with the approval, the validation. From the first time you perform and get that applause – sometimes as a child – it becomes part of your identity – This is my brother: he plays the piano. I think something happens psychologically where, if you’re not careful, that can become a source of validation. Applause. It’s like something digging into you. Something starts to be missing, you’re less self-sufficient in feeling good if it’s not there and you start to become dependant on outside factors for that feeling of approval and satisfaction.

The addictive roar of the greasepaint; the smell of the crowd

“What happens with a lot of musicians, particularly in the rock scene where the social environment has got that decadent element to it, is you come off the stage, you’ve had the applause, it might be a while before your next show, so you get fidgety and, in the absence of huge applause, you will perhaps try to get drunk or drugged instead to get to that feeling where it doesn’t matter.

“It doesn’t necessarily make for the nicest people. If I sit here and say: Oh, I love it when people scream for more, most ordinary people would say: Oh, that’s not the kind of person I want to be friends with: someone who loves it when people scream their name. That is what it boils down to.”

“It must have been interesting,” I said, “for one pianist to write about another pianist.”

The book grew out of a pianists’ dialogue

“The book grew out of a dialogue,” explained Clifford. “The starting point was this dialogue between us. I went back to LA three or four times and recorded conversations. I had about 25 hours solid.”

“And you are a pianist too,” I prompted.

“When I was six or seven,” Clifford told me, “my parents bought me a toy piano which rapidly became my favourite toy. So then they sent me to piano lessons with a little old lady called Miss Silley – Beryl Silley. I remember her having a huge photograph of Margaret Thatcher in the hallway.

“Around the age of ten, I started to get a little interested in pop music. My grandmother bought me a cassette tape of Elton John’s Honky Château album and that opened my eyes to the fact that playing piano was not just about playing Chopin or Beethoven to Miss Silley every week.

“What really made a difference to me, though, was David Bowie hitting the scene in about 1972/1973. I bought his album Aladdin Sane in 1973 and was completely hypnotised by the whole album. It has loads of wild, eccentric, crazy piano on it – unpredictable cadences and dis-chords. And, that, of course, was Mike Garson.

Clifford Slapper on the set of Ricky Gervais’ TV show Derek (Photograph by Ray Burmiston)

“I was hooked by Bowie – his voice and persona – and Mike Garson was the piano man on the albums and my own piano-playing became very tied-up with this, because I realised piano could be exciting and quite cool, because everybody at school was talking about this album. So you can imagine how I was very excited to work with David Bowie many years later and to meet Mike Garson.”

“So when,” I asked, “is your own autobiography coming out?”

“I’ve started work on it,” Clifford told me. “And I’ve got another rough structure for a book on addiction.”

3.5