In the second week of March 1975, David Bowie packed up his crates of books and a modicum of personal possessions at his rented New York City townhouse, a brownstone building on West 20th Street, and headed for the Amtrak terminal at Penn Station in Midtown Manhattan. The Thin White One had decided the city wasn’t big enough for him and Tony Defries, his cigar-comping Colonel Sanders-styled manager who’d set up the American base of his MainMan empire nearby, and from which Bowie was in the process of process of extricating himself from.

On a scarily creative pharmaceutical roll and having just just released Young Americans, his ninth studio album, Bowie was dancing a fine line between inspiration and psychosis, torn between a desire for stability and constant need to move, do, create. During this dark and troubled period his mounting paranoia, mania, and tension were evident in both sound and vision.

“David liked my apartment on 20th Street, and he also liked [drug supplier] Norman Fisher’s coke, something for which he’d recently acquired an insatiable appetite and for which I had, of course, hooked him up. And since my days were winding down with MainMan, I guess David felt comfortable getting high with me and opening up about anything and everything that was on his mind.” — Cherry Vanilla, Lick Me, 2010

Between various legal complications caused by the split with Defries and the decline of his relationship with his backing vocalist and one time protégé Ava Cherry, Bowie felt disenchanted with the Big Apple and needed a new adventure on a stranger shore.

Bowie enlisted a new manager, Michael Lippman, a Los Angeles-based entertainment lawyer, who would later represent George Michael. Lippman opened legal proceedings against Tony Defries and MainMan, seeking an end to their stake in his management, publishing and recording.

Though since enacting the costly litigation Bowie had next to no money coming in, so he decided to junk expensive condos on the East Coast for a cheaper alternative up West. He would spend the next few months couch surfing in Los Angeles as he waited for the call to start shooting his first Hollywood movie, a sci-fi extravaganza directed by Nicholas Roeg.

Bowie would end up living with Lippman and his wife Nancy, though first port of call was Deep Purple’s bassist Glenn Hughes, who he’d got to know during the Diamond Dogs tour the previous year.

“He asked to stay for a while at my place in Beverly Hills. I was in Germany but he came anyway – by train, alone… which was incredible for one of the world’s biggest stars. I arrived home five days later. At the time David was preparing himself for the role of The Man Who Fell Too Earth. For a while nobody knew he was in LA except me and Phil Daoussis, the guy who looked after me back then – not even David’s manager Tony Defries, or the members of his band. I was sworn to secrecy.”

Actually, when Daoussis picked Bowie up from LA’s Union Station on Sunday 16 March, Deep Purple were playing a concert in the birthplace of my grandfather, Belgrade, the capital of what was then Yugoslavia. After completing the band’s European tour in early April he arrived home in California three weeks later, but no matter, because there were drugs. Drugs. And lots of them.

Los Angeles offered Bowie a chance for a fresh start, although his chronically addictive behaviour and mental health issues swiftly deepened. Ten days later, Bowie, a bundle of scrawny-limbed energy at the best of times, was already ensconced in promotional duties for Young Americans, filming a Chuck Braverman directed clip for US TV.

Let’s not beat around the bush, Bowie had never looked thinner or iller. His state of mind was often agitated and manic – he claimed to see bodies fall past his window and began an unhealthy obsession with the occult. He was in the throes of an industrial sized cocaine addiction, snorting at least seven grams a day and famously subsisting primarily on a diet of cigarettes, red peppers and milk.

Unsurprisingly, he would stay awake for days on end. “I hate sleep,” he told Cameron Crowe in Playboy the following year. “I would much prefer staying up, just working, all the time. It makes me so mad that we can’t do anything about sleep or the common cold.”

Crucially, he weighed less than 95 pounds. That’s 40 kilos. And it showed. Oh boy, did it show. Watching the advert is like watching a singing skeleton. Literally.

In Los Angeles, Bowie’s life descended into a bipolarity of chaos and turmoil. He swapped Ava Cherry for the not dissimilar looking Ola Hudson, who would go on to design many of his clothes in this period but is probably better known as mum to Guns N’ Roses wild axeman Slash. And because it was convenient, The Dame bagged himself a boyfriend to go with the girlfriend, striking up an intimate “therapeutic” relationship with the man that was effectively his drug dealer. Sam Rey was a pretty aspiring model who Bowie would go on to immortalise in song as Sam Therapy on Sons Of The Silent Age, a song that found its way on to 1977’s “Heroes” but was conceived during the Hollywood highs some two years earlier.

I’ve interviewed scores of musicians, colleagues and crew about Bowie over the years, and of the ones who discussed his copious drug use, there is one factor that always sticks out, where they all sing from the same hymn sheet. From Tony Visconti to Jimmy Destri to even arch supplier Sam Rey himself (who now lives near me in Sydney, conveniently) they’re all united in utter admiration and astonishment at how David was able to hoover up incredible amounts of coke yet it never ever affected his work. Not once did he ever have to bail out of a recording session or live performance because he was too out of it.

Visconti even recounted one time during the recording of Young Americans at Philadelphia’s Sigma Sound Studios and panicking he was going to have a heart attack, just by trying (and failing) to keep up with the copious levels that Bowie was ingesting. When you listen to the LP, this is the sound of someone supremely in control, at the height of his powers. I once read the claim that the title track has more lyrics all by itself than the entire Low and “Heroes” albums combined. I wouldn’t swear to it, but it’s pretty damn likely. It is an incredibly wordy song. Bowie would eventually loathe it almost as much as Space Oddity, but I think it’s stood the test of time.

Soaking up everything black America had to offer, Bowie was listening incessantly to American soul and R&B acts like Aretha Franklin, Barry White, The Jackson 5, The Isley Brothers and the Kenneth Gamble/Leon Huff and Thom Bell productions for Philadelphia International Records, which were mainly recorded at the celebrated Sigma.

“At the end of the tour, he said, ‘Listen, I’m going to go to Philly and record. Do you want to come along?’” saxophonist David Sanborn says. The destination served as more than just a city with a recording studio. “I knew he was in love with American soul music, [especially] TSOP (The Sound of Philadelphia) and the Mother, Father, Sister, Brother records,” Sanborn explains. ”They’d had a real profound effect on him. That led him to want to go to Philly, to go where the stuff actually happened and absorb some of the vibe.”

When you think about Atlantic, Stax, Motown and Muscle Shoals, Philly Soul has to sit in there too, and Bowie wanted a piece of it. Americans respond greatly to flattery and vintage youth, so it’s no surprise that he finally cracked the Billboard Top 40 with Young Americans (backed with his David Live rendition of Knock On Wood). No sooner had Bowie completed the recording he was performing it on stage with his trusty acoustic guitar, making the song seem like a remnant of his curly haired folkie days, and eventually it was tumbled in with other congratulatory good-time songs of its era. Yet the reality is Young Americans is a cold and calculating piece of work, a schizophrenic soul ballad that becomes a diatribe, its polemic softened by Bowie’s authentic home grown backing singers.

“I didn’t know who Bowie was. But I did know this was the whitest man I’d ever seen – translucent white. And he had orange hair. He was thin and weighed about 98 pounds. At one point, I said he looked like shit and needed some food. ‘You need to let my wife make you some chicken, rice and beans, and fatten you up.’ Next thing I know, a limousine rolls up to my house in Queens.” — Carlos Alomar, 2013

In August 1974, Bowie booked time at Sigma Sound to record songs for the album he would later dismiss as “plastic soul.” While he had originally intended to work with Sigma’s house band MFSB*, with the exception of conga supremo Larry Washington they were unavailable due to a (cough) “scheduling conflict”**. “He wanted the people who were the session players from TSOP, but they didn’t want to do it,” recalls Robin Clark, wife of Bowie’s new rhythm guitarist, the ever funky Carlos Alomar. “But what David realised was that he could get the sound he was after by putting the right musicians and the right singers in a room.”

Instead, Bowie brought in several current members of his Diamond Dogs touring band, as well as some key new collaborators who would play a huge role in the album. Tagging along with Alomar and Clark was their friend, a 23-year-old aspiring singer and songwriter named Luther Vandross. The latter two, along for the ride and to give “moral support” to Alomar, were playfully riffing on one of the tracks in the studio; Bowie loved what he heard and had them sing on nearly every song on what was then known as The Gouster.

“David got that we worked well together,” Clark says. “But he also knew that he’d found something he didn’t even know he was looking for the minute he heard it. Then it was, ‘Now let’s do the rest of the album.’” Vandross, who became a highly sought-after jingle singer and arranger, and later a superstar in his own right, became Bowie’s secret weapon. “Luther came up with most of the background vocal parts,” says saxophonist David Sanborn. “He and David were very much collaborators.”

It was the first high-profile work of Vandross’ career, and he became The Dame’s de facto singing coach and vocal arranger for the sessions, providing much of the syncopated structure of the title track.

Asked by the NME about the song, Bowie told them there was

“No story. Just young Americans. It’s about a newly-wed couple who don’t know if they really like each other. Well, they do, but they don’t know if they do or don’t.”

The opening verses tell the story of two kid newlyweds progressively disenchanted with adult suburban life. They find a quantum of solace in sex, though it’s hardly ecstatic. With the line “It took him minutes, took her nowhere” you may as well call the bread-winner the egg timer. Eventually he frets that the next half century would just be going through the motions in ever decreasing circles. At least that’s what the final line of the third verse suggests: We live for just these twenty years, do we have to die for the fifty more?

8 Aug 1974: headlines being read by tourists in front of the White House © Bettmann/CORBIS

There’s mention of racial inequality, McCarthy witch-hunts and recently-disgraced President Nixon, and the ever-present anxiety of being a thoughtful white American who yearns for some meaningful expression. The whole song is wrapped in the ever-hopeful glow of that star-spangled American ethos, always grinning toward the next great chance for real happiness around the corner.

Nixon’s sudden appearance in the song’s bridge (a line that Bowie would update on stage to Reagan or Bush and sometimes even Lincoln) is partly just a topical contemporary note, as Bowie cut Young Americans in the middle of August, a few days after Nixon’s resignation over Watergate two hours away in Washington DC. Yet it’s also another dismissal, with Bowie accurately predicting that the downfall of POTUS No.37 would soon enough be reduced to history and tomorrow’s chip paper.

At the end of the track, our fictional heroine takes a bus to chase the counter-culture into more racially-diverse, and therefore more impoverished, neighborhoods. White counter-culture embraces the culture of immigrants and blacks, a culture as purely American as anything else, but it white counter-culture turns its findings into shiny new pop material – case in point, this very song. Thanks in no small part to Luther.

“So Dave, remind me how many words you changed on Funky Music again?”

Bowie called his new sound “plastic soul,” or “the squashed remains of ethnic music as it survives in the age of muzak rock, written and sung by a white limey.” It’s a crossroad between the superficiality of pop and its ever-lasting ability to mine those with real pain for the next quick inspirational fix. These were not totally unheard of references. Bowie described 1973’s Aladdin Sane as “Ziggy goes to America.” Its lead single The Jean Genie is as bluesy as freaky Martians get, but Philly Bowie differs from previous works in its sheer dive toward unabashed R&B.

Bowie regretted calling his album plastic soul and in a wide-ranging interview with Q magazine’s Paul du Noyer in 1990, he conceded the point:

“Yes, I shouldn’t have been quite so hard on myself, because looking back, it was pretty good white, blue-eyed soul. At the time I still had an element of being the artist who just throws things out unemotionally. But it was quite definitely one of the best bands I ever had. Apart from Carlos Alomar there was David Sanborn on saxophone and Luther Vandross on backing vocals. It was a powerhouse of a band. And I was like most English who come over to America for the first time, totally blown away by the fact that the blacks in America had their own culture, and it was positive and they were proud of it. And it didn’t seem like black culture in Britain at that time. And to be right there in the middle of it was just intoxicating, to go into the same studios as all these great artists, Sigma Sound. Good period—as a musician it was a fun period.”

45 years on from its release, Young Americans is rightly renowned as a classic example of the best brown and blue eyed soul from an English white boy this side of Elton John. Sigma made its mark on music history too, particularly in the 1970s and early ‘80s when artists across all genres — Madonna, Billy Joel, Patti LaBelle et al —recorded hit after hit in its Philly or New York City studios, being involved in more than 200 gold and platinum records.In 1996, Sigma began recording digitally, which, coincidentally, happened to be the year I paid pilgrimage to and got to meet Joe Tarsia, owner of the legendary Philadelphia studio, which was located quite centrally at 212 North 12th Street. Many of listeners’ greatest musical memories were made in that building, which, alas, was sold by Tarsia in 2003.

Two years later and Tarsia donated around 7,000 unclaimed tapes dating from 1969 to 1996 from the studio’s tape library to Philly’s Drexel University Audio Archive. With its own independent record label (MAD Dragon Music Group), an artist services firm, concert promotion company and a booking agency, Drexel’s Music Industry department is regarded as one of the finest in America.

One of the reel to reel tapes Drexel inherited, labeled “reel 4,” was a rehearsal recording from the August Sigma sessions that was inexplicably left behind by Bowie and Visconti. So that’s how a tiny but revelatory part of Bowie’s six-decade legacy is currently inconspicuously shelved in the basement of the University Crossings campus.

With reels 1, 2, 3 or more thought lost to the ages, Drexel Archives director Professor Toby Drexel created digital copies of “reel 4” to send to Bowie’s New York office. Isolar allowed Seay to keep the physical copy, the only known tape from the Young Americans sessions. That is, until a surprising series of events led Bowie himself to reels 1 and 2: like any good thrift-shopper, he discovered they were being hawked on eBay, the buying and selling site he scoured religiously on a daily basis (even buying from people like me). Being an astute documentarian of his own life, Bowie had Seay digitise reels 1 and 2 as well.

The Professor, of course, was the logical choice to retrofit these new finds, digitising the tracks and preparing the physical copies to be shipped to him. Being an occasionally benevolent type, Bowie let Drexel keep the digital tracks for their archives. But wait, there’s more.

Audio Archives also house a mysterious tape labeled simply “DB.” Seay found it accidentally one day and soon realised it was a recording of yet another Sigma studio session. This hour-long tape features Bowie practicing songs like Who Can I Be Now and (get this) at one point asking Luther to come in stronger on the “Who”. After demonstrating the kind of vocal he wanted, “DB” self-deprecatingly tells Vandross, “I mean, I’m not as good as you, but you know what I mean.”

It’s a fascinating work in progress document. So, not only did Bowie appreciate Philly’s music scene and the work of Gamble & Huff, but he kept in touch with the city via Drexel to maintain his scrupulous collection of his life’s work, leaving a little gift behind.

In May 2019, almost 23 years after I visited Sigma, I was able to book an appointment and obtain press access to Drexel’s hallowed basement and listen to numerous unreleased session takes from those early Young Americans rehearsals that are unavailable elsewhere. I’d just driven from Woodstock in upstate NY and a certain country pile on a mountain, so Bowie was certainly in my head.

Almost all of the tracks I heard are notably different from the released versions. On Young Americans itself, it’s Bowie singing live with the band as they attempt to learn the song, which comes across as a little sluggish. The lyrics are yet to be finalised and the montuno piano is very different. Quite Caribbean in fact.

Dated Sigma Sound Studios, Philadelphia 13 August 1974 is the first known session. The songs recorded were:

Reel 1 (13 Aug 1974)

John, I’m Only Dancing (Again)

Can You Hear Me

It’s Gonna Be Me

Reel 2 (13 Aug 1974)

Young Americans

Shilling The Rubes

I Am A Laser (written as Lazer)

After Today

Reel 3/“DB” reel

Studio chat, background vocals etc

Reel 4 (14 Aug 1974)

Young Americans

John, I’m Only Dancing

Can You Hear Me

It’s Gonna Be Me

After Today

If you’re wondering as to the nature and availability of the other tracks, prior to my visit Drexel were at pains to point out that if the visitor meets certain scholarly or professional criteria, “we do allow listening to the recordings, but due to intellectual property law, we are not allowed to distribute them. And, in the case of Bowie, Parlophone is particularly suspicious.” Which is why, for now, I’m only posting this short video of Young Americans for the purpose of research and study or criticism or review, which is permitted under the Creative Commons “fair use” in copyright law… as long as it’s under 60 seconds.

Those initial Sigma Sound recordings didn’t produce enough for a whole album. While there were some obvious winners, like Young Americans and a still unreleased attempt at Bruce Springsteen’s It’s Hard To Be A Saint In The City (a different Diamond Dogs/Station To Station hybrid version would be unveiled in 1989), some of the other material hadn’t evolved out of the jam stage, and the sessions, over time, had tended toward the slow and brooding.

As heartbreakingly confessional as Can You Hear Me and It’s Gonna Be Me were, an album dominated by seven-minute-long soul-styled torch ballads would have been a hard sell, especially for someone still considered a Max Factored glam rock star by most of the American public. So Bowie reconvened at Sigma in November and then, making a return to NYC, re-entered the studio that December and January 1975; the final session famously tracking Fame and a version of The Beatles’ Across The Universe with John Lennon and producer Harry Maslin, while Visconti, much to his chagrin, was mixing what he assumed was the finished album back in London.

As was Bowie’s wont, Young Americans would catch some listeners by surprise when it arrived in stores on 7 March 1975, but Visconti claimed not to have been caught off guard by the change in direction. “He’s been working to put together an R&B sound for years,” he insisted. “Every British musician has a hidden desire to be black.”

At Sigma (Terry O’Neill/Iconic Images)

Visconti expanded on that argument in a later conversation with Performing Songwriter, adding:

“Most British singers — and most English bands — grew up listening to early American R&B and blues. David was of that same ilk. He adored Little Richard and other R&B artists from the ’50s. He was also addicted to Soul Train. He watched it all the time and actually became the first non-black artist to appear on the show.

“So, it seemed obvious to make an R&B record – and what better place to do that than Sigma Sound in Philadelphia? So, yes, that album had its own world and universe. Before then, I don’t think we had worked with any black musicians. That album, to this day, sounds terrifically fresh. It’s one of my favourite Bowie albums.”

[Editor’s note: Gino Vannelli was actually the first white act to be on Soul Train, appearing in February 1975. Bowie wasn’t a guest until the November, by which time Elton John and the Average White Band had also been on the show.]

Interestingly, for the depressingly inevitable Record Store Day 2020, a new live official bootleg is being released from the Bowie camp via Parlophone. I’m Only Dancing (The Soul Tour 74) is a double album recorded mostly during Bowie’s performance at Detroit’s Michigan Palace on 20 October 1974 with the encores taken from Nashville’s Municipal Auditorium on 30 November, both said to be sourced from somewhat inferior cassette recordings. Still, it’s the fullest live representation of the then unreleased Young Americans album to date, with six of its tracks related to the Sigma sessions. Boogie down with David now, y’all.

With thanks to Toby Seay, Ryan Moys, Joe Tarsia and Eric Stephen Jacobs.

Steve Pafford

*Album tracks like Somebody Up There Likes Me seem like Bowie’s attempts to mimic the MFSB sound, with organ subbing for the string section and the chorus of (primarily) Luther Vandross, Ava Cherry and Robin Clark as the equivalent of the Three Degrees. David Sanborn’s saxophone has to fill in for MFSB’s entire 10-plus horn section, which gets a little tedious, but Carlos Alomar on guitar, often hitting on downbeats, holds his own, giving a much needed kick to the track.

**Glenn Hughes has also revealed Bowie asked him to fly to Philly to sing back ups but his Deep Purple bandmate Ritchie Blackmore demanded he decline, fearing that the professional association with a carrot-topped bisexual wouldn’t go down well with their resolutely rock audience.

BONUS:

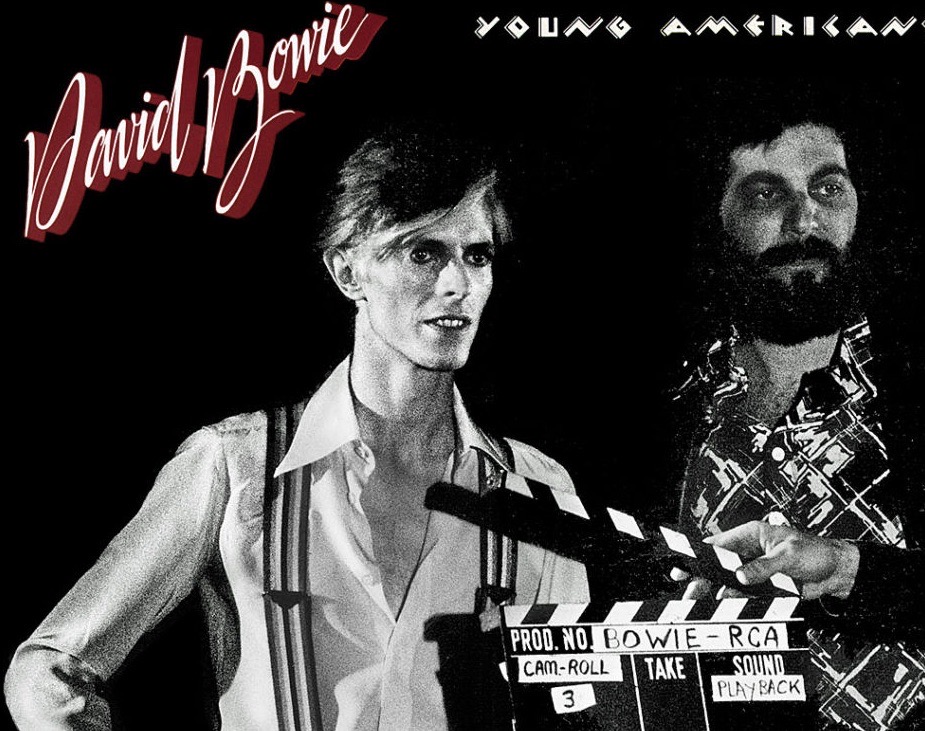

“One day I was in the studio and the phone rang and it was Bowie himself, and he said he wanted to do a photo shoot like my After Dark magazine cover with Toni Basil, only with him in it. So they flew me out to LA, where he was on the Diamond Dogs tour, and we shot the cover in this movie studio place with the big old fashioned lights and stuff. I was just a kid, I was really nervous, but I got the picture. I hand tinted that with oil colour and they loved it.

“Had I had more experience at the time I would have told him to take off that godawful shirt. I could not stand that shirt! But I wasn’t assertive enough to say ‘David, you must change your wardrobe.’ David was great though. Very down to earth. Then we did another session a little while later in New York, the one with the American flag [used on 2008’s iSelectBowie and 2016’s The Gouster], doing cocaine and staying up all night, and we hung out at his townhouse in Chelsea.” — Eric Stephen Jacobs, talking to Steve Pafford, March 2020

info www.stevepafford.com

Fantastic period! Luckily, the dame survived and many classics followed!