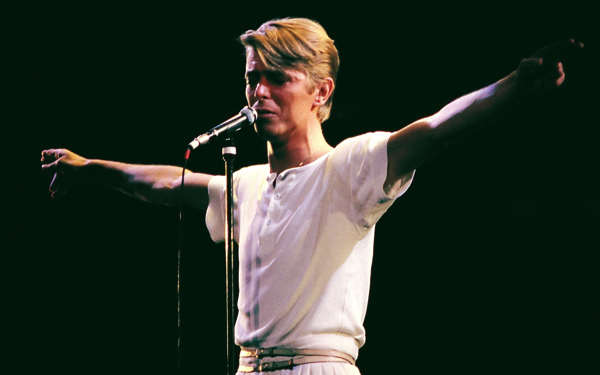

David Bowie performing live in 1978. A new box set collects all of Bowie’s albums released between 1977 and 1982

In 1980, David Bowie was in the middle of a new kind of transformation. After launching himself to stardom in 1969 with his first hit single, “Space Oddity,” he spent a decade morphing from Major Tom to Ziggy Stardust to Aladdin Sane to Halloween Jack to The Thin White Duke — a series of characters that also emblemized radically different approaches to rock music, from sci-fi glam to stark experimentalism. By the end of the ’70s, however, he dispensed with such alter egos. Instead, he absorbed them all into a single if mercurial persona, one known simply as David Bowie. And that persona hinged on “Ashes To Ashes.”

His 1979 album, Lodger, wrapped up a groundbreaking, three-album collaboration with Brian Eno that had yielded his most acclaimed work to date, including the full-lengths Low and “Heroes.” But the final installment of this Berlin Trilogy also exhausted Bowie and Eno’s partnership. Lodger, as excellent as it was, felt anticlimactic. At the end of the year, he recorded a new version of “Space Oddity” for British television, and it was an eerie resurrection of the character that had put him on the map: Major Tom, the lost astronaut cast adrift in space, an existentialist casualty of humankind’s quest to conquer the heavens. For the restlessly forward-looking Bowie, this reprise of “Space Oddity” seemed tainted with an odd nostalgia, and it felt like a loop being closed. On top of it all, Bowie separated from his wife of ten years, Angela, with their divorce set to be finalized in February of 1980.

He began the new decade with his blankest slate since his pre-fame days in the ’60s. But after owning and defining the ’70s, what was Bowie to do in the uncharted waters of a new decade, especially when it had become predictable for him to reinvent himself? Enlisting his longtime friend and producer Tony Visconti, he responded with Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps). Recorded in New York and London throughout early 1980, the album took the sprawling innovation of The Berlin Trilogy and whittled it down into more digestible, if no less challenging, pop songs. “Ashes To Ashes” was the lead single. It also marked the return of Major Tom. The new song, released in August of 1980, was the sequel to “Space Oddity,” something Bowie blatantly made clear in the opening verse: “Do you remember a guy that’s been / In such an early song? / I’ve heard a rumor from Ground Control / Oh no, don’t say it’s true.” Eleven years had passed since “Space Oddity.” In that time, much had changed for Major Tom, as it had for Bowie. Left to decay in space, he’d grown paranoid and addicted to drugs: “Strung out in heaven’s high / Hitting an all-time low.”

For Bowie, “Ashes To Ashes” was anything but a low. It became his second number-one single in the U.K. His first had been, funnily enough, a reissue of “Space Oddity” in 1975. To capitalize on this, Bowie’s label, RCA Records, released a promotional single in 1980 titled “The Continuing Story of Major Tom.” On it, “Space Oddity” was mixed smoothly into “Ashes to Ashes,” creating a nine-minute epic. The end of the first song meshed uncannily with the start of the second: The lonely beeping at the conclusion of “Space Oddity” bled into the high-pitched, pizzicato-like melody at the beginning of “Ashes to Ashes.” It was as if that had been Bowie’s intention all along.

At the same time, the mix dramatically demonstrated just how far he’d progressed in the ’70s. His voice was now deeper and more profound. The music was jagged, jarring, and richly textured in a completely different way than “Space Oddity” had been. Rather than psychedelically spacious, it carried a sterile air of computers, androids and off-kilter motorization. Guitarist Chuck Hammer conveyed this feeling with layers of synthesized guitar. Flangers gave a grand piano an alien quality. Dennis Davis’ drums were disorienting yet mathematical, a funk beat from another dimension.

In the booklet that accompanies the new Bowie box set A New Career In A New Town (1977-1982), Visconti calls the song’s rhythm “a mind-bender. Your brain tells you this isn’t supposed to work.” In The Complete David Bowie by Nicholas Pegg, Bowie said that Davis “had in incredibly hard time with it, trying to play it and turn the beat backwards.” No one, though, had a harder time in “Ashes To Ashes” than Major Tom. Voiced by Bowie, he runs through a litany of memories, regrets, and hallucinations, along with a desperate desire to get better: “I’m hoping to kick / But the planet is glowing.” He wishes to free his caged psyche as well as his exiled body: “Want an axe to break the ice / Wanna come down right now.

Most poignant of all is the song’s indelible bridge, in which Bowie laments, “I never done good things / I never done bad things / I never did anything out of the blue.” The spacesuit drops away, and Bowie himself stands there, naked and afraid. “Those three particular lines represent a continuing, returning feeling of inadequacy over what I’ve done,” he said in Peter Doggett’s book The Man Who Sold The World. “I have a lot of reservations about what I’ve done, inasmuch as I don’t feel much of it has any import at all.” It was a rare and mature show of vulnerability in someone who, for so long, had cloaked himself in concept and costume.

David Mallet, who had directed the video clip of Bowie’s 1979 version of “Space Oddity,” was asked to helm the video for “Ashes To Ashes.” At the time it was the most expensive pop video ever, shot a year before MTV launched in 1981 and proving that music videos were viable promotional investments. It aided immensely in the song’s popularity, despite being as edgy and jarring as the song itself. Mallet used the new computer graphics workstation Paintbox to radically alter the color palette of the short film, rendering the sky black and the ocean pink. Bowie alternates between portraying a clown, an astronaut, and the inmate of an insane asylum — paralleling the many roles he’d played in his career.

In his book David Bowie: A Life, Dylan Jones recounts an anecdote that sheds light on the artist’s self-reflective frame of mind in 1980: “An old man searching for driftwood on the beach was asked to move away from the set. When Mallet pointed at Bowie and asked the old man if he knew who he was, the old man replied, ‘Of course I do. It’s some c*** in a clown suit.’ Bowie later said, ‘That was a huge moment for me. It put me back in my place and made me realize, “Yes, I’m just a c*** in a clown suit.”‘” Three years later, Bowie’s next album, the crowd-pleasing Let’s Dance, became the bestselling record he’d ever enjoy. And in his footsteps, hordes of successful new-wave artists, from The Human League to Duran Duran, followed.

But before he got there, the self-reflection in a handful of Bowie’s late-1970s songs began to bleed over into self-reference. Singing in the first person, he imbued “DJ” — one of Lodger‘s best singles — with a hint that performing his hits over and over had dehumanized him. “I am a DJ / I am what I play.” At the same time, the song could be read as both a tribute and taunt aimed at the radio industry who programmed so much of Bowie’s fate. And on “Fashion,” another single from Scary Monsters, Bowie mercilessly dissected a core component of his persona to an extent he hadn’t done since 1975’s “Fame.” In both “DJ” and “Fashion,” Bowie’s turn toward contained, catchy experimentalism — rather than the sprawling avant-garde scope of Low and ‘Heroes’ — is both obvious and bracing. “Ashes to Ashes” was part of a continuum, a deliberate use of cutting-edge technology, studio techniques, harsh textures, and minimalism in the pursuit of elevating pop music while preserving Bowie’s image as a sonic iconoclast.

“Ashes To Ashes” fades out on an unsettlingly note, with a nursery-rhyme chant of “My mama said, to get things done / You’d better not mess with Major Tom.” In singing these lines, Bowie disobeyed them. He was messing with Major Tom after having resigned him to cosmic limbo over a decade earlier. “When I originally wrote about Major Tom, I was a very pragmatic and self-opinionated lad,” he says in The Complete David Bowie. “Here we had the great blast of American technological know-how shoving this guy up into space, but once he gets there he’s not quite sure why he’s there. And that’s where I left him. Now we’ve found out that he’s under some kind of realization that the whole process that got him up there had decayed, was born out of decay; it has decayed him, and he’s in the process of decaying.” He also called the song “the end of something,” adding, “I was wrapping up the ’70s really for myself, and that seemed a good enough epitaph for it — that we’ve lost [Major Tom], he’s out there somewhere, we’ll leave him be.”

Other artists did not leave Bowie’s famous spaceman be, most famously the German synth-pop star Peter Schilling in his 1983 hit “Major Tom (Coming Home),” which basically amounted to fan fiction in song form. Bowie also broke his own rule. He unearthed Major Tom once more in his 1995 song “Hallo Spaceboy,” co-written with Eno. In the lyrics, Bowie bids farewell to his doomed astronaut: “Spaceboy, you’re sleepy now / Your silhouette is so stationary.” And in “Blackstar,” Bowie’s final video before his death in 2016, the visor of a spacesuit is raised, revealing a bejeweled skull that may or may not have belonged to Major Tom. By building on the character throughout the decades, Bowie finally found a resting place for Major Tom: in the pantheon of pop mythology. But it was “Ashes To Ashes” that consummated Major Tom’s role as a postmodern folk hero — and gave Bowie closure to his most momentous decade.

5