Often seen as the poor third in the Berlin Trilogy, Ben Graham argues that it only shines when examined in isolation

So, what do you think of Lodger, then? Chances are, if you think of it at all, you think of it as the weakest link in Bowie’s so-called ‘Berlin Trilogy’; the third part, after Low and “Heroes”, that isn’t quite so memorable or influential or icy cool; the one that, if you really think about it — which you tend not to — doesn’t actually fit in with its two illustrious forebears at all.

Thirty years on, still no-one is quite sure where to place Lodger. In a way, that’s appropriate: as the title suggests, it’s a record that doesn’t quite belong anywhere. In fact, the only way to really appreciate Lodger is to remove it from the trilogy which, arguably, doesn’t even exist in the first place. The whole ‘Berlin Triptych’ idea was in many ways a deliberately pretentious marketing gimmick that Bowie cooked up after the fact, probably because he had no other notion of how to sell such an offbeat and disjointed collection of songs as Lodger to the public. It’s all part of the bigger picture, he assured them, and you need this one to complete the set; but it was a set he almost certainly didn’t have in mind when he began recording Low back in September 1976 — not in Berlin, but at the Chateau D’ Herouville just outside Paris, where he’d also been working with Iggy Pop on The Idiot throughout the previous summer.

1977’s “Heroes” and Lust for Life were recorded back-to-back in Berlin’s Hansa Studios, it’s true, but Bowie bade Berlin Auf Weidersehn after sleepwalking through his part in David Hemmings’ Weimar decadence-by-numbers flick Just A Gigolo at the beginning of 1978. He spent the rest of that year touring the world, and drew a line under this period of his career with the patchy double live album Stage, released in September 1979. When he finally went home it wasn’t to Germany, but to Switzerland, where he’d been officially resident for tax reasons since 1976. And it was here that he recorded Lodger, during breaks from touring and afterwards in the early part of 1979. To further distance it from its two predecessors in this supposed trilogy, when Lodger was finally released that May it was after the longest gap between Bowie studio albums since Space Oddity.

But, of course, there is one other factor that these three albums have in common, and that’s Brian Eno. Producer Tony Visconti called Eno Bowie’s Zen Master: constantly popping up in the studio with suggestions of how to do things differently for the sake of it, or of how to make life more difficult for the thin white duke in order to arrive at new creative destinations. Accounts suggest, actually, that by the time of Lodger Bowie was wearying of Eno’s deliberately perverse working methods. But ultimately the album represents their fullest collaboration, the record where David most wholeheartedly adopted Brian’s oblique strategies and embraced errors and random events.

Consider this: Bowie had already worked out the concept of Low, written the songs and indeed recorded pretty much all of the first side of the album before Eno even showed up. “Heroes” was deliberately constructed along the same template, albeit with Eno and his EMS synthesiser on board from the start. But Lodger was the first project where the two collaborated to work up an album’s worth of songs from scratch, and as such rates as perhaps the most literally experimental album of Bowie’s career.

Eno is all over Lodger like randomly-hung wallpaper. Guitarist Carlos Alomar (a veteran of the Harlem Apollo’s house band, and Bowie’s no-nonsense musical director since Young Americans), remembered Brian telling the band, in his most proper and reserved middle-class English accent, to lay down a funky groove, and then pointing a stick at a blackboard on which he’d written some of his favourite chords, instructing them to change to the chord indicated after four bars. “I finally had to say, this is bullshit, this sucks,” Alomar recalled. Eno and Bowie even considered recording the entire album around the same chord changes, but in the end only two songs shared this structure: album opener, ‘Fantastic Voyage,’ and the lead-off single, ‘Boys Keep Swinging’.

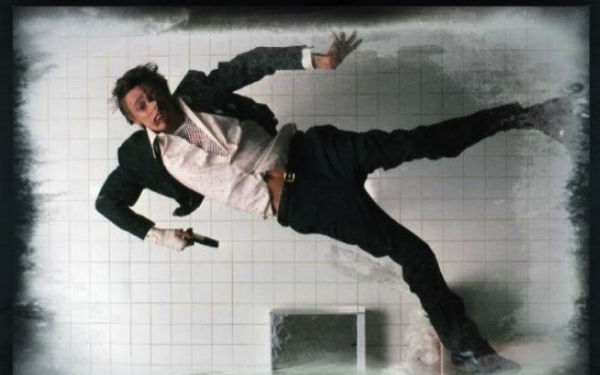

Eagerly awaited as Bowie’s first new material for two years, ‘Boys’ initially appeared to be a jolly, frivolous glam garage stomp, apparently inspired by the Village People’s recent hit, ‘YMCA’. A similarly camp celebration of the opportunities available to the male gender, the tongue-in-cheek fun initially obscured the subtext, a criticism of sexual inequality. But it took the song’s video to reveal a third, more disturbing layer to the song: a video in which a macho, strutting Bowie intoned the lead, then dragged up to play three rather lethargic female backing singers, including an unsmiling old lady with a cardigan and walking stick, who seemed the ”realest” Bowie of all. The implication was that both male and female gender stereotypes were equally contrived and false; interestingly, after the clip was shown on Top of the Pops, the single plummeted from the charts

Bowie on the Kenny Everett Video Show

In the climax to the ‘Boys’ video, the three dragged-up Bowies each stalk down a catwalk in slow motion, removing their wigs and smearing their lipstick across their faces with the back of their hands. This was a direct allusion to Roman Polanski’s 1976 movie The Tenant, in which Polanski plays a Polish immigrant who takes on a Paris apartment after the previous occupier has committed suicide. Polanski spends much of the film in drag, tormented by his own neuroses and fears, and eventually jumps out of the window himself. Interestingly, like Lodger, The Tenant was itself supposedly the last, and least acclaimed, part of a trilogy, following up two major critical successes, in Polanski’s case, Repulsion and Rosemary’s Baby.

A surreal psychological thriller dealing with issues of identity, alienation, paranoia, persecution and madness, The Tenant was always going to appeal to Bowie, and Lodger covers many of the same themes. The influence is acknowledged in both the title, and the LP’s bizarre cover. A broken-nosed Bowie, limbs splayed as though he’d recently fallen from a great height and with one hand bandaged (a crucial allusion to the film), was photographed in a grisly Polaroid light and spread across the gatefold sleeve, so that the album cover itself consisted merely of a pair of blurry, black-trousered legs and the title scrawled across a postcard, running vertically along the right-hand side. There was no track listing evident anywhere: the gatefold opened up to reveal an assortment of cryptic photographs, including the corpses of Che Guevara and Jesus Christ, and a couple of wristwatches. David certainly wasn’t going out of his way to sell this one in Woolworths.

Lodger also marked Bowie’s long-delayed political awakening. One important aspect of his time in Berlin was the time spent talking with left-wing street intellectuals, who seem to have finally persuaded him to shake off the fascination with fascist and Nietzchean imagery he’d played with since as far back as ‘The Supermen’ on The Man Who Sold The World. It was a fascination, of course, that would reach its nadir during the cocaine-addled Station to Station era, when Bowie, dressed in severe ‘30s garb and slicked back hair, proclaimed that Britain was ripe for a fascist leader, and that he’d be a great choice because he’d be dictatorial and quite mad — a qualification which shows more self-awareness and humour than he’s been given credit for, but nevertheless when compounded by a supposed Nazi salute from the back of his open-top limo outside Victoria Station, and the general political climate of mid-seventies Britain at the time, you can see why Bowie might want to backtrack.

The album’s opening track, ‘Fantastic Voyage’ explicitly rejects this notion of the one strong leader: the fantastic voyage is life itself, dangerously threatened by the proliferation of nuclear weapons and, specifically, the possibility of the man with his finger on the button being an unstable depressive who may one day decide to end it all, quite literally — not just by doing himself in, but by triggering Armageddon. Bowie draws parallels between the language of Cold War propaganda and the mindset of someone deep in a state of paranoid depression, where other people are dehumanised and everyone is out to get you, and where concepts of dignity and loyalty become more important than the raw fact of living, so losing face and a sense of shame become so overwhelming that suicide seems the only solution. “We’re learning to live with somebody’s depression,” Bowie concludes, adding “I’m still getting educated…”

Elsewhere, Eno’s experimentation is evident on ‘African Night Flight,’ based apparently around the old rock standard ‘Suzie Q,’ not that you’d ever know. A strange, blurred snapshot of a song, it anticipates the likes of ‘Mea Culpa’ on Eno and David Byrne’s My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, released two years later. ‘Move On,’ meanwhile, was written by playing along with a backwards recording of ‘All The Young Dudes,’ then playing that version backwards for Bowie to croon over in his best contemporary Scott Walker fashion, with the banal travelogue lyrics at odds with the strangeness of the musical arrangement.

Eno, of course, had come straight from producing and collaborating on the last two albums by Talking Heads, and the New York band are a huge influence on Lodger. Bowie was a fan anyway: invited, on Lodger’s release, to play two hours of his favourite music on a Radio One Star Special, he chose several Talking Heads numbers. And although the main riff of ‘Yassassin’ recalls Bowie’s own ‘Fame,’ and the snaking Arabic melody is played by former Hawkwind violinist Simon House in very similar style to ‘Hassan-i Sabbah’ from the Hawks’ 1977 set Quark, Strangeness and Charm, the mix of uptight, psychoanalysed New York intellectualism over a world music groove is pure Heads; the song would also find distinct echoes on the Bush of Ghosts track, ‘Regiment.’

Equally, although Bowie has claimed that ‘Red Sails’ is directly influenced by Neu!, and the motorik beat, whooshing synths and crunching guitar are all present and correct, his vocals seem to parody Byrnes, especially on the “fa-fa-far away” section towards the end. And the neurotic funk of ‘DJ’ is simply the best Talking Heads song that Bowie ever wrote: detachment, alienation and some great distorted wah guitar from Adrian Belew, who Bowie had poached from Frank Zappa’s band and who would go on to work with, yes, Talking Heads, making important contributions to Remain In Light and becoming a crucial part of their live line-up during 1980-81.

Some of the credit for Belew’s astonishing guitar parts on Lodger must go to Eno however, as he was effectively sampling his guitar, splicing together different takes that used different tones and effects units, often taking only seconds at a time, and piecing together freaky atonal solos that were physically impossible to reproduce live. Belew contributes a great scraping feedback part to ‘Boys Keep Swinging,’ where he was the only musician to stick to his regular instrument- in an attempt to make the song more punk, Bowie and Eno got guitarist Carlos Alomar to play drums and drummer Dennis Davis to play bass. Alomar’s drumming is endearingly rubbish, but Tony Visconti overdubbed the crucial bass hook. Within weeks, ‘Boys’ had been covered by the Associates, who released their own haunting, strangely empty but gorgeous rendition as their debut single.

‘Repetition’ was also swiftly honoured with a cover version, this time by the Au Pairs, who included it on their debut album, 1981’s Playing with a Different Sex. You can see why: the queasily elastic bass and taut, menacing rhythm immediately find sympathy with the scratchy DIY punk-funk scene, even before you get to the lyrical subject matter of domestic violence against women. Indeed, while many of the punks had been teenage Bowie fans already, Lodger saw the maestro reconnecting with his progeny after his years in exile. Rejecting the straight rock tradition in favour of funk, avant-garde and world music, the album shares the post-punk urge to reinvent rock/pop as a more fluid, ambiguous and open-ended medium.

The lyrical engagement with gender politics is again representative of the cultural zeitgeist, but Bowie isn’t necessarily taking a feminist angle on ‘Repetition’: his disconnected, half-spoken vocal merely describes the scene, actually taking the point of view of Johnny, the male protagonist, which makes his laconic delivery all the more disconcerting. This non-judgemental reportage style owes a debt to Dave’s old mucker Lou Reed, and even fellow New York street poet Alan Vega – Johnny and Suicide’s Frankie Teardrop could almost be brothers.

The album ends with ‘Red Money,’ an odd choice to close the set, being basically ‘Sister Midnight’ a four-year-old Bowie song that he’d since given to Iggy Pop, but with new lyrics and an altered vocal melody that emphasised the song’s rhythmic qualities. Coming after the seminal version on The Idiot, it can’t help but feel like a pointless retread, and yet it somehow works; perhaps because the words seem to have a deep personal significance to Bowie, with allusions to a red box that would turn up frequently as a recurring motif in his paintings in later years, apparently symbolising responsibility.

And responsibility, in the end, is the real theme of Lodger: taking us back to the opening track’s worries over the fate of the entire planet resting in the hands of one flawed, capricious human being, through to ‘Repetition’s’ description of how we pass on our pain to those closest to us, full of self-pitying victimhood yet unaware we’ve become the aggressor. From the crippling banality of ‘DJ’- a man with the ears of millions of believers, yet nothing to say- to the cocooned self-absorption of ‘Boys Keep Swinging,’ and the damp squib of a judgement day portrayed in ‘Look Back in Anger.’ The last words on the album are “Such responsibility- it’s up to you and me.”

It’s this sense of responsibility – both individual and collective – that finally separates Lodger from the so-called Berlin albums. Low was, in Bowie’s own words, “Isn’t it great to be on your own, let’s just pull down the blinds and fuck em all”, a celebration of self-pity. “Heroes” saw the individual begin to fight back, but still from a passive-aggressive, me-against-the-world standpoint. It’s only with Lodger that Bowie realises that to survive in any meaningful sense, he has to engage with society, and with the rest of the human race.

This theme of engagement and responsibility would continue on Scary Monsters, Bowie’s next album, while Eno would develop Lodger’s fusion of New York funk and world music textures on Talking Heads’ Remain In Light (with Belew), and on My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. And Bowie and Eno would work together again on 1995’s Outside, a record that curtailed Bowie’s late eighties/early nineties wilderness years, and which in many ways picked up where Lodger left off.

Lodger’s working title was Planned Accidents. It’s not a concept album, and it would be foolish to read too much into what is, in many ways, a series of random experiments. But as Eno’s methods have proved – as well as those of Bowie’s literary hero, William Burroughs – when you trust in chance, you may get more cohesion and insight than you bargained for. Thirty years on, it’s a record that sounds as fresh as ever, perhaps partly because it’s been largely ignored for so long. Maybe it’s finally time for Lodger to come in from the cold.

Originally published in November 2009

5