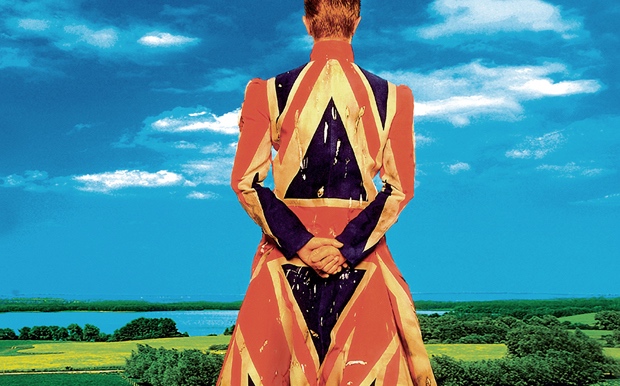

Bowie, both insider and outsider, marked his 50th year by issuing his fist self-produced album since “Diamond Dogs

Context is everything when it comes to music fandom. Anyone who became a fan of the Rolling Stones circa the disco-fied hit “Miss You” likely views the band entirely differently than someone who first saw Mick Jagger and Company on “The Ed Sullivan Show.” The same goes for Prince: Fans who fell in love with him during his “Purple Rain”-era MTV heyday have a far different take on his career than anyone whose first exposure came when he was known as a glyph.

Pointing out that context matters isn’t meant to be a value judgment, of course. Purity tests used to determine when someone started liking a band or artist are pointless and divisive rather than unifying. When someone is first exposed to an artist at an odd stage of his or her career (a time of unorthodox sonic exploration, for example, or after the release of a dud album), however, it permanently colors perception in intriguing (and often unexpected) ways.

David Bowie music fandom is an especially interesting case study. During his days as a bleached-blond MTV icon, Bowie projected a rather mainstream persona. Seeing him tanned and dapper in the 1983 video for “Let’s Dance” or striking a bar-band leader pose in 1984’s “Blue Jean” video made his ’70s otherworldly TV interviews and deliberately weird performances (such as on “Saturday Night Live”) seem like a distant memory.

But by the ’90s, when the misfits and freaks he once cavorted with suddenly became mainstream, Bowie became both an insider and an outsider. On the one hand, he was cooler than ever because a younger generation worshipped him. Nirvana covered “The Man Who Sold the World” on “MTV Unplugged.” Bowie toured with Nine Inch Nails, a band riding high on 1994’s “The Downward Spiral.” And his 50th birthday bash, held in 1997, featured acts such as The Cure, Smashing Pumpkins and Foo Fighters. Bowie was one of the alternative movement’s patriarchs, the godfather of unorthodoxy.

At the same time, he was deeply engaged with modern music and his own current creative endeavors, which placed him in the odd situation of being both a living legend and a vibrant contemporary artist. Bowie had faced this problem in the 1980s as well, and turned to his fallback coping mechanism: dramatic reinvention. He formed the band Tin Machine and re-established his weirdo credentials by playing Jareth the Goblin King in “Labyrinth.”

“Tin Machine was very important, ’cause it decontextualised me,” Bowie told the Independent on Sunday in 1995. “After that, nobody had any idea what I was supposed to be. It enabled me to rebuild what I enjoyed doing the most.”

And so Bowie in the ’90s approached his legacy by modernizing it — and, in some cases, trying to one up it. That led to one of his most underrated studio albums, “Earthling,” which turns 20 years old on Feb. 3. The first self-produced Bowie record since 1974’s “Diamond Dogs,” the bracing LP incorporates the serrated drum ‘n’ bass and electronic textures dominating music in the 1990s.

Two “Earthling” highlights, “Little Wonder” and “Battle for Britain (The Letter),” boast skittering drums that careen like a pinball machine, as well as industrial-flavored guitar aggression. The latter song also possesses sliced-and-diced, mad-genius piano. Distorted vocal effects and club-worthy programming — as on the stomping, dystopian Day-Glo highlight “Dead Man Walking” and the 8-bit-synthrock hellmouth “The Last Thing You Should Do” — further smear the lines between the organic and synthetic.

“I wanted to go whole-hog and do a real combination of hard rock and jungle, and I think that two or three times on the album, we come really close to it,” Bowie told Pulse in 1997. “‘Little Wonder’ is a really good song and ‘Battle for Britain’ is a really extraordinary piece of music,” he said.

“Then again, I tend to like and favor songs that at the time are not liked or even noticed, really,” Bowie continued. “I stick with those and often I’m proved right in the end. None of my [favorites] were big singles or anthemic pieces, yet I knew those songs were good and lasting.”

This reads like typical Bowie contrarianism or eclecticism, although the statement is acutely self-aware. At the time, the phenomenon of artists’ incorporating then-fashionable electronic textures into their music felt suspiciously like trend hopping. Bowie, in contrast, observed that drum ‘n’ bass is “jazz-based,” as he told The Baltimore Sun in 1997. “From its inception, it had such interesting breakbeats that any drummer worth his salt wanted to work out how on Earth he could get involved in it. I guess it’s the nearest thing that we’ve had to a respectable version of [jazz] fusion.”