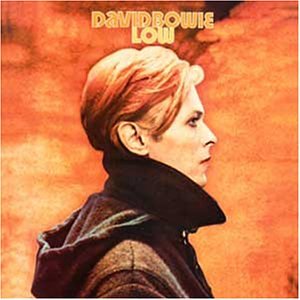

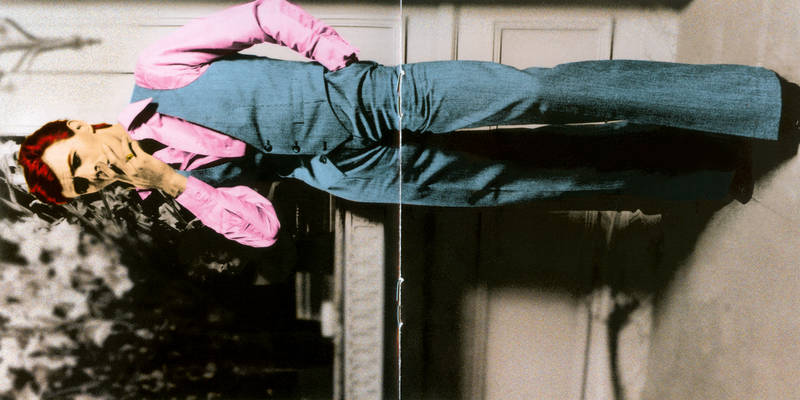

Low is the eleventh studio album by British musician David Bowie, co-produced by Bowie and Tony Visconti. Widely regarded as one of Bowie’s most influential releases, Low was the first of the “Berlin Trilogy”, a series of collaborations with Brian Eno (though the album was mainly recorded in France and only mixed in West Berlin). The experimental, avant-garde style would be further explored on “Heroes” and Lodger. The album’s working title was New Music Night and Day

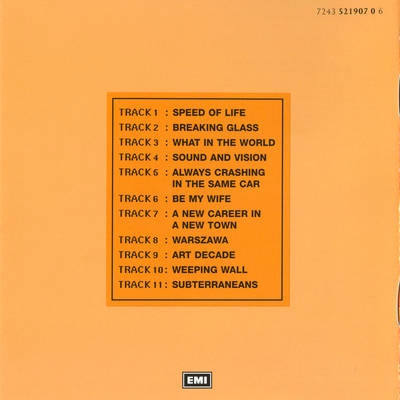

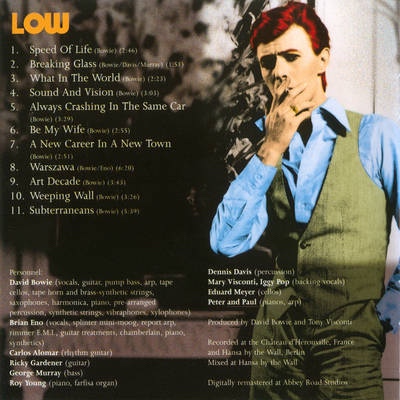

All lyrics written by David Bowie; all music composed by David Bowie except where noted.

01 “Speed of Life” – 2:46

02 “Breaking Glass” (Bowie, Dennis Davis, George Murray) – 1:52

03 “What in the World” – 2:23

04 “Sound and Vision” – 3:05

05 “Always Crashing in the Same Car” – 3:33

06 “Be My Wife” – 2:58

07 “A New Career in a New Town” – 2:53

08 “Warszawa” (Bowie, Brian Eno) – 6:23

09 “Art Decade” – 3:46

10 “Weeping Wall” – 3:28

11 “Subterraneans” – 5:39

Reissues

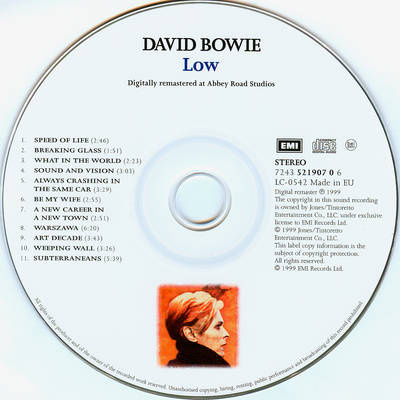

The album has been released three times on CD, the first between 1984 and 1985 by RCA Records, the second in 1991 by Rykodisc (with three bonus tracks on silver CD and later on AU20 Gold CD), and the third in 1999 by EMI (featuring 24-bit digitally remastered sound and no bonus tracks).

The Rykodisc edition of this album was released in the United Kingdom on CD, Cassette and LP in 1991 by EMI Records. The three bonus tracks were added to the end of side two of the LP and cassette editions so not to spoil the original running order.

CD: Rykodisc / RCD 10142 (US)

“Some Are” (previously unreleased) – 3:24

“All Saints” (previously unreleased) – 3:25

“Sound and Vision” (1991 remix by David Richards) – 4:43

also released by EMI in the UK (CDP 79 7719 2)

SINGLE RELEASE

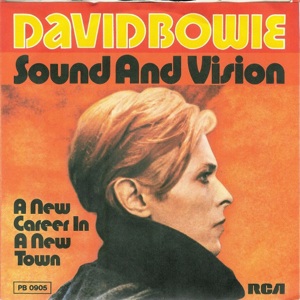

“Sound and Vision”

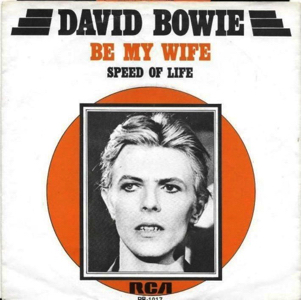

“Be My Wife”

“Sound and Vision” was used by the BBC on trailers at the time. This provided considerable exposure, much needed as Bowie opted to do nothing to promote the single himself, and helped the song to No. 3. The song was also a top ten hit in Germany, Austria and the Netherlands. However, it stalled at No. 87 in Canada and only managed No. 69 in the United States where it signalled the end of Bowie’s short commercial honeymoon until “Let’s Dance” in 1983.

The first live performance of the song was at Earl’s Court on 1 July 1978. In 1990, it was a regular number for Bowie’s greatest hits Sound + Vision Tour. The name had also been used for Rykodisc boxed set anthology in 1989.

“Be My Wife” was the second single from Low after “Sound and Vision”, but it became the first new Bowie release since “Changes” to fail to break into the UK chart.

“Be My Wife” was frequently played live on the various tours after its release and Bowie is said to have repeatedly announced this song during live performances as “one of my favourites,” as may be seen or heard in such concert footage or audio recordings.

UNCUT magazine interviews Tony Visconti in 1999:

UNCUT: Low is generally perceived as David at his most emotionally honest, but most unhappy. Looking back, is this interpretation accurate?

TV: I wasn’t a difficult album to make, we were freewheeling, making our own rules. But David was going through a difficult period professionally and personally. To his credit, he didn’t put on a brave face. His music said that he was “low.”

UNCUT: Is it true that Chateau d’Herouville was haunted by the ghosts of Chopin and George Sand (David refused to sleep in master bedroom ‘cos it was spooked? Eno woken by taps on the shoulder in the middle of the night?). Any good ghostly happenings you recall?

TV: I keep reviewing my feelings about the supernatural. There was certainly some strange energy in that chateau. On the first day David took one look at the master bedroom and said, “I’m not sleeping in there!” He took the room next door. The master bedroom had a very dark corner, right next to the window, ironically, that seem to just suck light into it. It was colder in that corner too. I took the bedroom because I wanted to test my meditation abilities. I never admitted this before. I had read that Buddhists in Tibet meditated all night in a graveyard to test their level of fear/no fear. Milarepa, the Tibetan saint, sat on his dead mother’s body all night and meditated. It felt like it was haunted as all fuck, but what could Frederic and George really do to me, scare me in French? I loved the look of the room so I decided to spend one night there. If something happened I planned to shout so loud I’d wake up the village.

Eno claims he was awakened early every morning with someone shaking his shoulder. When he opened his eyes no one was there.

UNCUT: There are rumours that Robert Fripp was involved on Low, but uncredited. Was he?

TV: He wasn’t there, ever. Only Ricky Gardiner, David and Carlos Alomar played guitar on Low.

UNCUT: Rumour also has it that an alternative version exists with different lyrics – is this true, and if so, why?

TV: I remember David wrote a third verse to Always Crashing In The Same Car and sang it in the style of Bob Dylan. It was done half in jest, but we were a little freaked because Dylan had just been in that motorcycle accident and this seemed like bad taste, I guess. David asked me to erase it and I did. I can’t recall there being any alternative lyrics to any other songs.

UNCUT: There’s a story about Dennis Davis recounting a tale (during Low sessions) of being thrown out of the army after seeing a UFO crash. What do you remember of this, if at all?

TV: Dennis was the life of the party. He could do a mime act on the closed-circuit-tv camera and have us in stitches. He claimed he took a short cut through a highly classified hanger and saw a crashed UFO from the catwalk he was on. He stared at it for ages until a guard told him to leave because he wasn’t classified to be there. He was warned not to ever mention what he saw. I don’t know if this is true, but it was highly entertaining. French TV sucks, Dennis is the best we had.

UNCUT: There’s a credit on Low for Peter and Paul. Is this to do with Mary being there? And who were they really?

TV: Brian and Mary sang the “doo-doos” in the beginning of Sound and Vision. Mary and our kids were there for a couple of weeks.

UNCUT: Does it still annoy you that some people still think Eno produced the ‘Berlin’ albums?

TV: Yes. David’s set the record straight many times since, and of course my name is in the credits as co-producer with David. How rock journalists continue to make that mistake is beyond me. Come to think of it, I don’t recall Brian ever setting the record straight. I know that David and Brian spent some time together before going in the studio with me, but they were writing. Brian spent an average of three weeks on each the Triptych albums recording his bits. He wasn’t present for the vocals, lots of other overdubs and the mix.

UNCUT: I’ve always thought that there’s a prevailing mood of hope throughout Low (certainly not a pessimistic album). Do you think that comes through?

TV: I find Warszawa very uplifting. Despite a few really bad days we had quite a lot of fun making Low, especially when all the radical ideas were making sense and things were starting to click. I remember after a couple of weeks of recording I made a rough mix of the entire album so far and handed a cassette of it to David. He left the control room waving the cassette over his head and grinned ecstatically saying, “We’ve got an album, we’ve got an album.” I have to qualify that statement by saying that at the beginning, the three of us agreed to record with no promise that Low would ever be released. David had asked me if I didn’t mind wasting a month of my life on this experiment if it didn’t go well. Hey, we were in a French chateau for the month of August and the weather was great!

UNCUT: Is it true that, when David asked what your Eventide Harmonizer did, you blurted “It messes with the fabric of time!”? How revolutionary do you think that sound was you created? And its influence in later years?

TV: I actually said, “It fucks with the fabric of time,” much to the delight of David and Brian, who were on a conference call with me at the time. I must’ve been quoted in a family magazine.

It was a radical sound, especially on the drums. I had the second Harmonizer in Europe and I guessed it would be a matter of time before other producers figured out what I was doing. But when the album came out the Harmonizer still wasn’t widely available. I had loads of producers phoning me and asking what I had done, but I wouldn’t tell them. I asked, instead, how they thought I did it and I got some great answers that I found inspirational. One producer insisted I compressed the drum tracks three separate times and slowed the tape down every time, or something like that. I also used the Harmonizer to great effect on some vocals, but especially on side two.

I’ve heard hundreds of “Low sounds” on other records since.

UNCUT: You’ve described recording ‘Low’ as pretty horrible. Do you remember much of the various incidents (food poisoning, French press infiltration, etc.)?

TV: In August most of Europe goes on holiday. This studio was no exception. The service was terrible. After three days I noticed that the sound got duller and duller and I asked my assistant, a lovely English chap, when was the last time the multitrack recorder was lined up? He said about a week before we arrived then the technician went on holiday. My assistant was brand new, hired just for us because he could speak English and French. He didn’t know how to maintain the machines. So every morning I’d go into the control room with him and we’d line up the machine together, with the manual open, hoping for the best.

The food was appalling. For the first three days they served nothing but rabbit and no vegetables. I was starving. When I asked for a little salad or something, they plopped six heads of lettuce on the table with a bottle each of vinegar and oil, plus more rabbit.

We would get ravenous at night so we’d eat this cheese that they left out uncovered since dinner. David and I got food poisoning as a result. Even the French doctor couldn’t be bothered to look at me because I got out of bed to request that he see me after David. He said, “He’s okay, he can walk!” David shared his medicine with me.

A French woman was hired to be our assistant. She was supposed to provide us with anything we might need to make the recording go smoothly, but even she couldn’t be bothered to bring some bread, cheese and wine up to the studio when we called down for some at 1am (a normal working hour for a rock studio). I remember David getting the owner out of bed at that hour and saying in precise, measured out words, “We want some bread, some cheese and some wine in the studio ? now! What, you’re asleep? Excuse me, but I thought you were running a studio

UNCUT: What impressed you initially with Ricky Gardiner?

TV: He was totally left-field and completely savvy with special effects. I was in awe of him.

UNCUT magazine interviews Bowie in 1999:

UNCUT: Many reasons have been suggested for moving to Berlin: the local art and music scene, to escape superstardom, for spiritual and physical detox – plus the creative stimulation of being in an isolated, edgy, divided city. Are these theories accurate? Can you remember why the city appealed?

Bowie: Life in LA had left me with an overwhelming sense of foreboding. I had approached the brink of drug induced calamity one too many times and it was essential to take some kind of positive action. For many years Berlin had appealed to me as a sort of sanctuary-like situation. It was one of the few cities where I could move around in virtual anonymity. I was going broke; it was cheap to live. For some reason, Berliners just didn’t care. Well, not about an English rock singer anyway.

Since my teenage years I had obsessed on the angst ridden, emotional work of the expressionists, both artists and film makers, and Berlin had been their spiritual home. This was the nub of Die Brucke movement, Max Rheinhardt, Brecht and where Metropolis and Caligari had originated. It was an art form that mirrored life not by event but by mood. This was where I felt my work was going. My attention had been swung back to Europe with the release of Kraftwerk’s Autobahn in 1974. The preponderance of electronic instruments convinced me that this was an area that I had to investigate a little further.

Much has been made of Kraftwerk’s influence on our Berlin albums. Most of it lazy analyses, I believe. Kraftwerk’s approach to music had in itself little place in my scheme. Theirs was a controlled, robotic, extremely measured series of compositions, almost a parody of minimalism. One had the feeling that Florian and Ralf were completely in charge of their environment, and that their compositions were well prepared and honed before entering the studio. My work tended to expressionist mood pieces, the protagonist (myself) abandoning himself to the zeitgeist (a popular word at the time), with little or no control over his life. The music was spontaneous for the most part and created in the studio.

In substance too, we were poles apart. Kraftwerk’s percussion sound was produced electronically, rigid in tempo, unmoving. Ours was the mangled treatment of a powerfully emotive drummer, Dennis Davis. The tempo not only ‘moved’ but also was expressed in more than ‘human’ fashion. Kraftwerk supported that unyielding machinelike beat with all synthetic sound-generating sources. We used an R&B band. Since Station To Station the hybridization of R&B and electronics had been a goal of mine. Indeed according to a 70’s interview with Brian Eno, this is what had drawn him to working with me.

One other lazy observation I would like to point out, by the way, is the assumption that Station To Station was homage to Kraftwerk’s Trans-Europe Express. In reality Station To Station preceded Trans-Europe Express by quite some time, 76 and 77 respectively.

By the way, the title derives from the Stations of the Cross and not the railway system.

What I was passionate about in relation to Kraftwerk was their singular determination to stand apart from stereotypical American chord sequences and their wholehearted embrace of a European sensibility displayed through their music. This was their very important influence on me.

Interesting sidebar. My original top of my wish list for guitar player on Low was Michael Dinger, from Neu. Neu being passionate, even diametrically opposite to Kraftwerk.

I phoned Dinger from France in the first few days of recording but in the most polite and diplomatic fashion he said ‘No’.

UNCUT: Some biographers speculate the Berlin era was an instinctive reaction to the mid-Seventies ethos of punk rock – dressed down, blunt, serious, doom-laden, emotionally raw. A plausible theory?

Bowie: Whether it was my befuddled brain or because of the lack of impact of the English variety of punk in the US, the whole movement was virtually over by the time it lodged itself in my awareness. Completely passed me by. The few punk bands that I saw in Berlin struck me as being sort of post 1969 Iggy and it seemed like he’d already done that. Though I do regret not being around for the whole Pistols circus as that kind of entertainment would have done more for my depressed disposition than just about anything else that I could think of.

Of course, I had met them fairly early on when I was touring with Iggy, at least Johnny and Sid. John was obviously quite in awe of Jim but on the occasion of meeting Sid, Sid was near catatonic and I felt very bad for him. He was so young and in such need of help..

As far as the music goes, Low and its siblings were a direct follow-on from the title track Station To Station. It’s often struck me that there will usually be one track on any given album of mine, which will be a fair indicator of the intent of the following album.

UNCUT: Was there ever a serious plan to record with Kraftwerk, as some biographers claim?

Bowie: No, not at any time. We met a few times socially but that was as far as it went.

UNCUT: Did you cruise the autobahns listening to Autobahn non-stop, as Ralf Hutter once insisted?

Bowie: Certainly on the streets of LA in 1975, yes. But by Berlin Autobahn was rather last year’s news. So, in short , no.

UNCUT: Were there any meetings or planned collaborations with other ‘Krautrock’ bands like Cluster, Neu! or Tangerine Dream?

Bowie: Not at all. I knew Edgar Froese and his wife socially but I never met the others as I had no real inclination to go to Dusseldorf as I was very single minded about what I needed to do in the studio in Berlin.

I took it upon myself to introduce Eno to the Dusseldorf sound with which he was very taken, Connie Plank et al (also to Devo by the way, who in turn had been introduced to me by Iggy) and Brian eventually made it up there to record with some of them.

UNCUT: Low is generally perceived as David at his most emotionally honest, but most unhappy. Looking back, is this interpretation accurate?

Bowie: Yes, it was a dangerous period for me. I was at the end of my tether physically and emotionally and had serious doubts about my sanity. But this was in France. Overall, I get a sense of real optimism through the veils of despair from Low. I can hear myself really struggling to get well.

Berlin was the first time in years that I had felt a joy of life and a great feeling of release and healing. It’s a city eight times bigger than Paris remember and so easy to ‘get lost’ in and to ‘find’ oneself too..

UNCUT: Is it true that Chateau d’Herouville was haunted by the ghosts of Chopin and George Sand, and David refused to sleep in the master bedroom because it was spooked? Did this affect the record’s mood?

Bowie: It was a spooky place. I did refuse one bedroom, as it felt impossibly cold in certain areas of it. To my knowledge though, the place itself had no bearing on the form or tonality of the work. The studio itself was a joy, ramshackle and comfy feeling. I liked the room a lot.

UNCUT: There are rumours that Robert Fripp was involved, but uncredited. Was he?

Bowie: No.

UNCUT: Rumour also has it that an alternative version exists with different lyrics – is this true, and if so, why?

Bowie: If there had been different lyrics to anything, then I’m sure they would have been working lyrics or ‘placement’ words to identify a melody that I wanted to use. I do remember singing joke words to some of the melodies but I frequently do that when I’m getting a feel for where I want it to go. Tony would have wiped or recorded over them when I put down final vocals. I’m not aware of any existing alternative versions.

UNCUT: The couplet in Breaking Glass which begins “don’t look at the carpet” – is this a reference to drawing cabbalistic symbols on the floor in LA?

Bowie: Well, it is a contrived image, yes. It refers to both the cabbalistic drawings of the tree of life and the conjuring of spirits

UNCUT: Is it true that Weeping Wall, Subterraneans and Some Are were left over from David’s proposed soundtrack to The Man Who Fell To Earth?

DB: The only hold over from the proposed soundtrack that I actually used was the reverse bass part in Subterraneans. Everything else was written for Low.

Bowie in Record Mirror, September 1977:

Warszawa is about Warsaw and the very bleak atmosphere I got from the city.

Art Decade is West Berlin – a city cut off from its world, art and culture, dying with no hope of retribution.

Weeping Wall is about the Berlin Wall – the misery of it.

Subterraneans is about the people who got caught in East Berlin after the separation – hence the faint jazz saxophones representing the memory of what it was.

Brian Eno speaking to Michael Watts:

“I know he liked Another Green World a lot, and he must’ve realised that there were these two parallel streams of working going on in what I was doing, and when you find someone with the same problems you tend to become friendly with them. He said when he first heard ‘Discreet Music’ he could imagine in the future that you would go into the supermarket and there would be a rack of ‘Ambience’ records, all in very similar covers. And – this is my addition – they would just have titles like ‘Sparkling’, or ‘Nostalgic’ or ‘Melancholy’ or ‘Sombre’. They would all be mood titles, and so very cheap to buy you could chuck them away when you didn’t want them any more.”

Eno (in 1980): “The way he worked impressed me a lot. Because it reminds me of me. He’d go out into the studio to do something, and he’d just come back hopping up and down with joy. And whenever I see someone doing that I just trust that reaction. It means that they really are surprising themselves.”

Ricky Gardiner (guitars): “As for the style of music, I think you’ll find that Bowie doesn’t reject any kind of music. He’s not a musical pseudo-intellectual. He likes Mantovani, for example, which may make some people go into double-think. In actual fact it makes complete sense. Mantovani is brilliant, there’s no getting away from that, and Bowie knows it. I think he was very disappointed by the music for The Man Who Fell to Earth. He spent quite some time writing a score for it, and he wasn’t pleased it wasn’t used in the film. He let us hear it and it was excellent, quite unlike anything else he’s done.”

====================

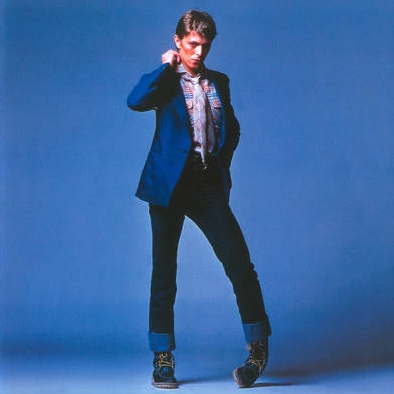

David Bowie Low Sessions 1976

David Bowie Low sessions at the Chateau d’Herouville 1976, featuring all the band and Tony Visconti and Brain Eno, kids and crew.

Behind the scenes photos by Ricky Gardiner’s Nikkormat camera and Kodachrome film.

Music: Night/ Songs for the Electric Ricky Gardiner and Virginia Scott

.

[real3dflipbook id=”101″]